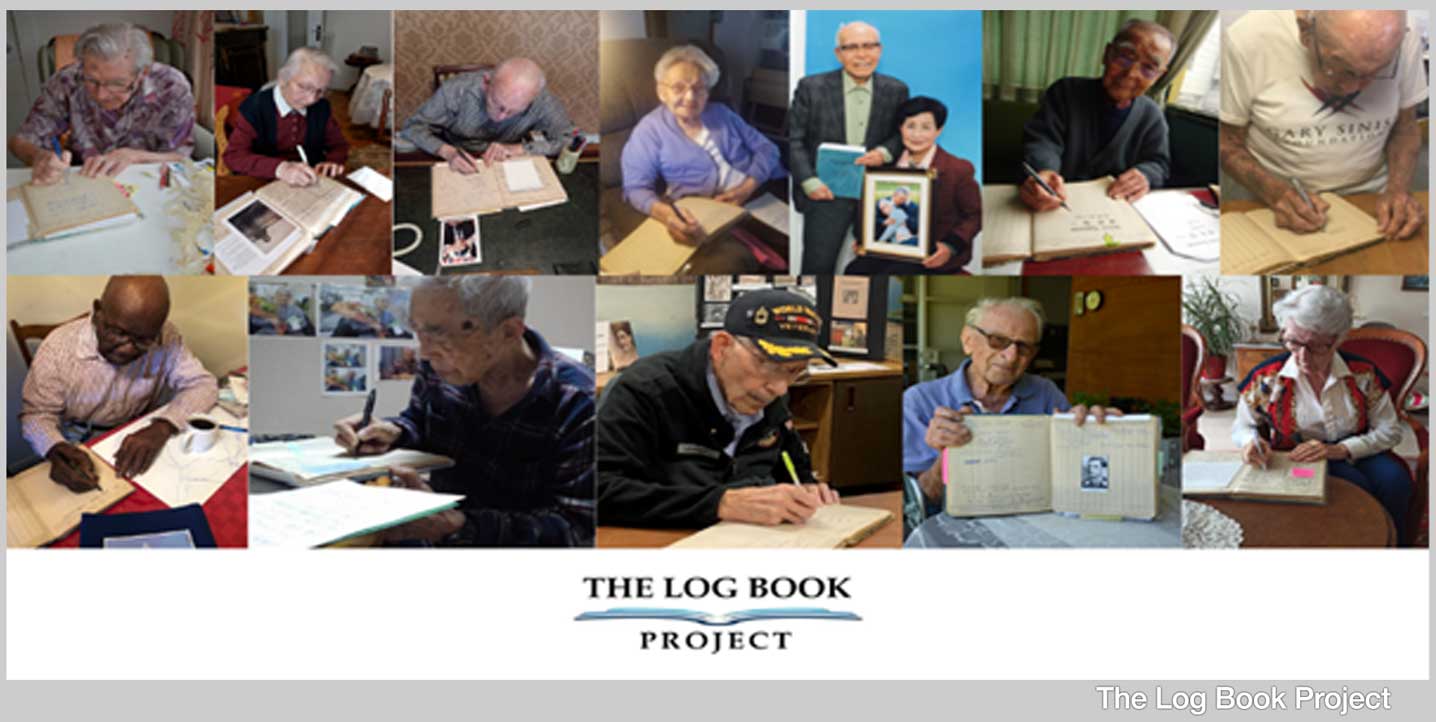

The average age of the signatories at the time they put pen to paper was close to 100. They served on both sides of the war across various fronts. Their number includes the author of the book that inspired the film "Schindler's List," kamikaze pilots, female spies, survivors of death marches and nurses.

The logbook, which has traveled the equivalent of seven times around the world, has a flight schedule that is managed by Nicholas Devaux, an accountant residing on the Caribbean Island of St. Lucia. It belonged to his father, Cyril, who served as a pilot in Great Britain's Royal Air Force. At the time, young men from British colonies like St. Lucia were recruited to support the war effort.

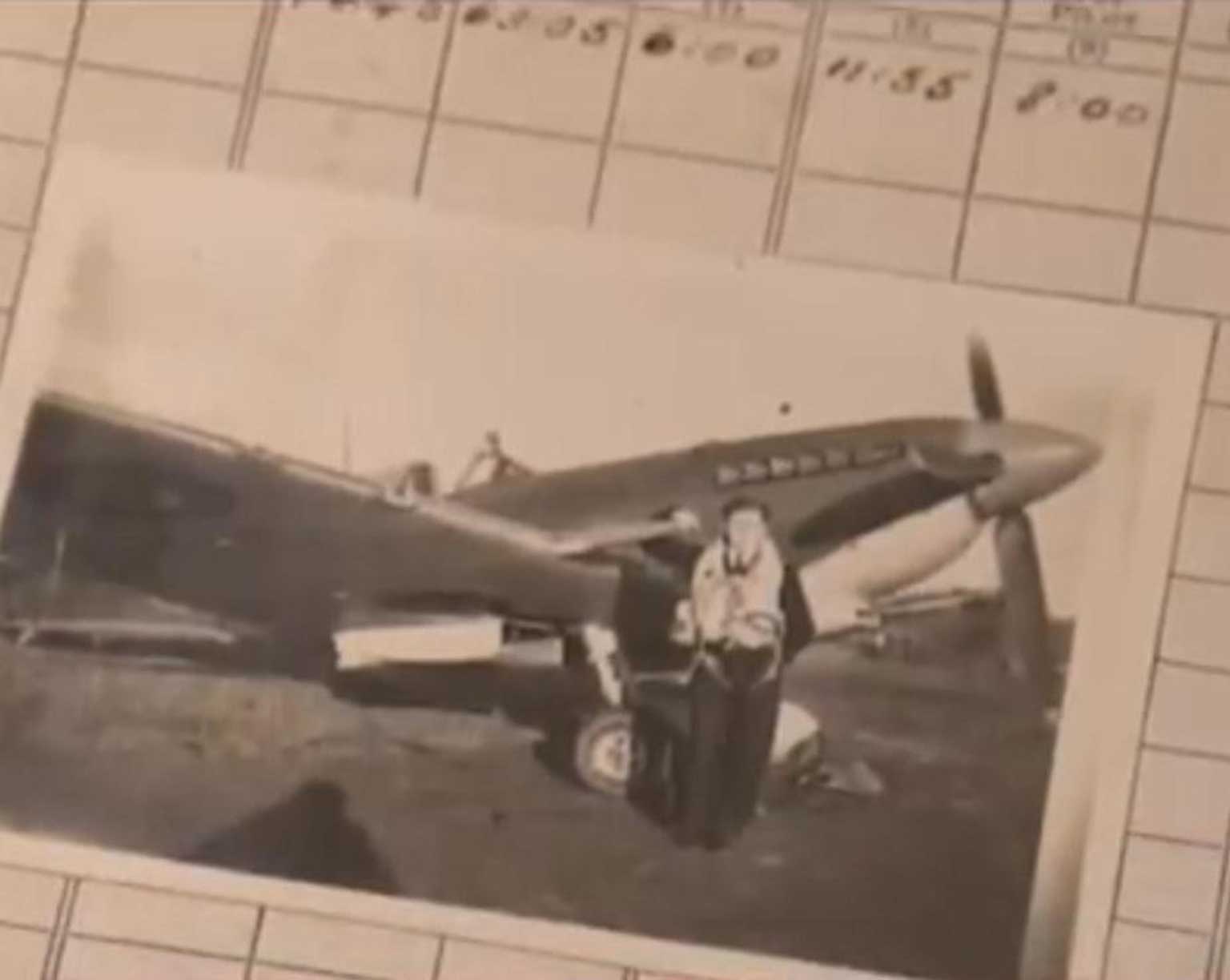

Devaux's father never spoke about the war after his military discharge. When Devaux was 11, he stumbled upon the logbook in his mother's cabinet. The first few pages were filled with training details of maneuvers and missions in his father's impeccably neat handwriting. But Devaux was most fascinated by the logbook's aircraft photos.

That discovery sparked Devaux's lifelong interest in the war's history and, in particular, fighter pilots. Devaux tells NHK World: "So much of what we live in now is shaped by the structures of post-World War Two. Even now, we see that Russia is invading Ukraine over the issue of NATO and that came about from World War Two alliances of nations."

The project began in Japan

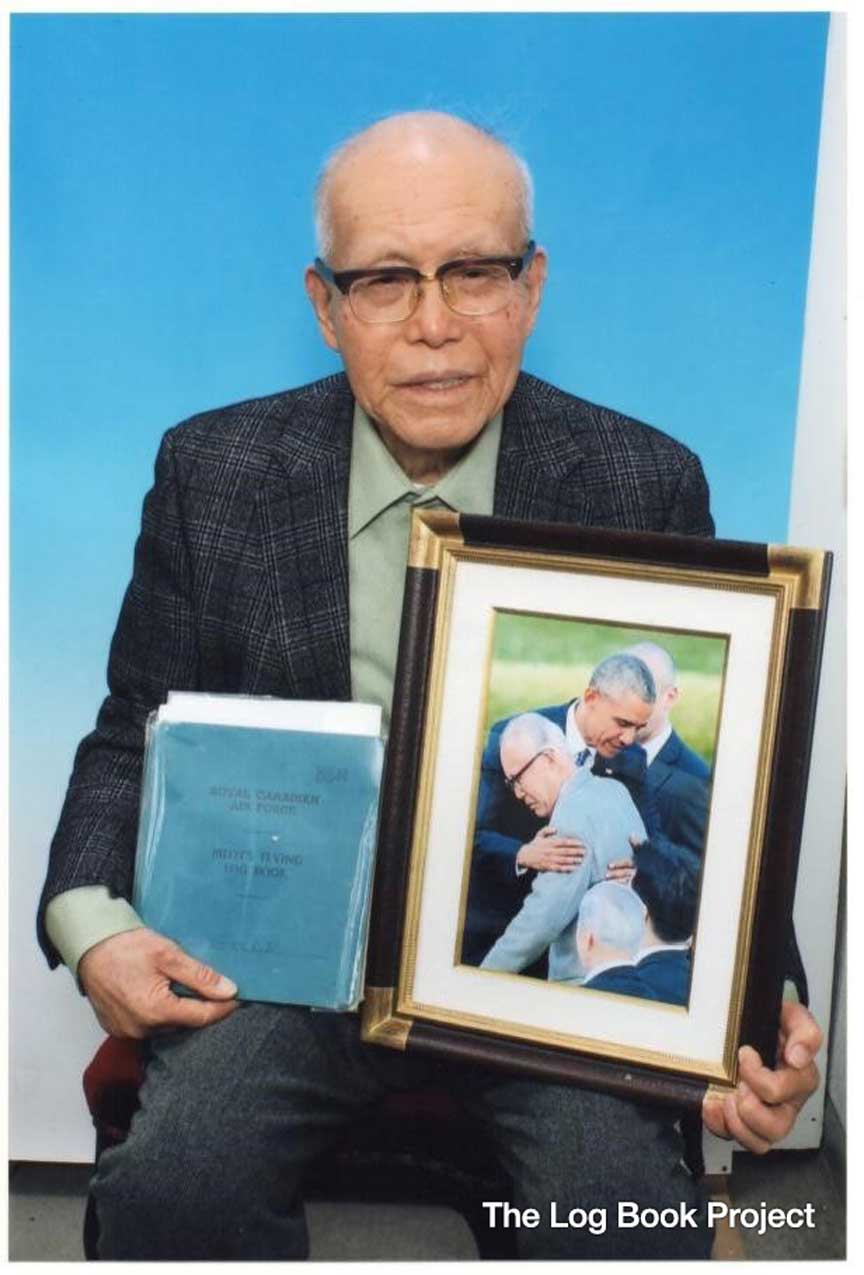

In 2016, Devaux came across a news article about Harada Kaname ― one of the last surviving Zero fighter pilots who took part in the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack. After the war, haunted by the guilt of killing people in combat, Harada became a peace activist. When a colleague was going to make a business trip to Japan, Devaux asked him to take his father's logbook with him to get it signed by Harada. It took some convincing, but his colleague eventually agreed to help.

Devaux got in touch with Harada's family through a Japanese contact and they said yes. But Harada, 99, died before the logbook reached him. As fate would have it, however, US President Barack Obama was visiting Japan at the time to deliver a speech at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. The image of Obama embracing Hiroshima atomic bombing survivor Shigeaki Mori prompted Devaux to ask Mori to be the logbook's first signatory. Mori agreed.

When the logbook finally returned to Devaux in St. Lucia, the sight of Mori's signature deeply moved him. Devaux says: "Here was a man who survived the atomic bombing. And I thought there must be other people out there like him with profound experiences of World War Two that I can document."

The power of a signature

Devaux knew it would be a race against time to collect the stories. Through tireless research and recommendations, the logbook's pages began to fill up.

Devaux usually sends the book to a signatory and arranges for it to be forwarded to the next one. So for most of the time, the logbook is out of his possession.

But in the age of the internet, why bother to send an actual book?

"Our whole world is so digital," says Devaux. "Everything is copied and pasted. But when you actually see someone's handwriting, that's something very personal and you know that they've held on to this book and gone through the names and learned about other stories, and it just makes it come alive. This is much more than my father's book now ― this belongs to the whole world."

Still, The Logbook Project isn't just paper-based. A supporter helped Devaux set up a website, thelogbookproject.com, which tracks its journey, publishes the signatories' backstories and allows the global network of veterans to connect with one another.

Visiting Tokyo, logbook in hand

Devaux got his first chance to visit Japan in November 2022 on a business trip to Tokyo. He brought the logbook to have it signed by more veterans.

Devaux's first stop in Tokyo was at a kendo dojo to meet 96-year-old Odachi Kazuo, a former kamikaze pilot. Kamikaze aviators formed a special military unit that carried out suicide attacks against Allied ships in the late stages of the war.

At 16, Odachi joined the Imperial Japanese Navy's pilot training course and became a kamikaze pilot a year later, in 1944. He carried out eight missions, but every time his attempts to strike Allied aircraft carriers were thwarted by poor weather, engine trouble or enemy pilots. His eighth and final mission came just before noon on August 15, 1945. As he was taxiing for takeoff, a groundman waved for him to stop. The Emperor had just announced Japan's surrender. The war was over. His life spared, Odachi went on to become a police officer and kendo instructor.

"Going to war was wrong," says Odachi. "Yet, I voluntarily signed up to fight in it. How naive I was! Even now, sometimes in my dreams I recall friends who died in the war."

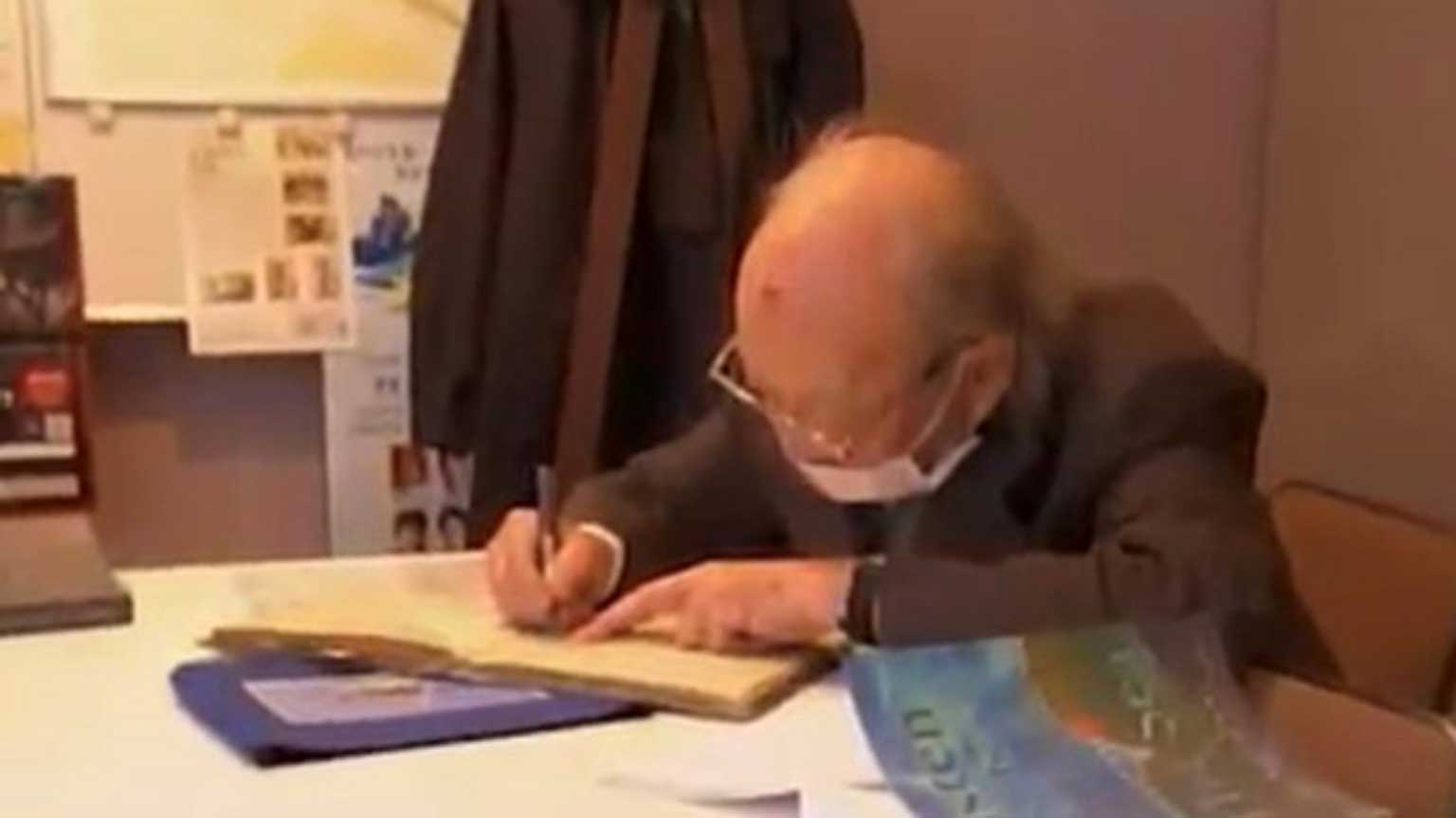

To understand more about Japan's wartime experience, Devaux visited a museum dedicated to university students who were sent to the frontlines during the late stages of the war.

The Wadatsumi no Koe Museum is run by Okada Hiroyuki, a 93-year-old academic. A high school student at the time, Okada lived through the US bombing of Tokyo on March 10, 1945, which killed an estimated 100,000 civilians.

"Even though I was just a student, I was antiwar," says Okada. "I knew this war had started with Japan's invasion of China. The international situation in the 1930s and 40s was very complicated, but there should have been a way to avoid war. To resignedly accept the war, to believe that war was the only way and that Japan was the highest culture in the world ... was wrong. Understanding each other, and each other's history and culture, is very important."

Okada's message in the logbook reads:

We must strive to never start war.

Ongoing wars must be stopped.

Victors should not be proud.

The defeated must regain their confidence.

Remembrance and reconciliation

Reconciliation is another theme of The Log Book Project. The logbook highlights the unlikely story of mortal enemies who went on to become friends.

Devaux had read about US Air Force ball turret gunner Lester Schrenk, whose B17 bomber was nearly shot down by a German fighter pilot while on a mission over Denmark. After the pilot of the badly damaged B17 signaled his surrender, the German pilot stopped firing and escorted them to occupied Denmark ― sparing them from an icy death in the North Atlantic. Schrenk spent 15 months as a prisoner of war, and his brutal experiences included an 800-kilometer death march in freezing temperatures to escape the oncoming Soviet Army. But he never forgot the German pilot who allowed his B17 to land safely.

Six decades later, when Schrenk got his first computer, he was determined to track down the German pilot so he could thank him for sparing his life. He eventually identified the pilot as Hans Hermann Muller – and learned that he was still alive.

He initiated contact through a letter and their correspondence resulted in an emotional reunion in Muller's hometown. The April 2012 event was extensively covered by the local media. They exchanged war stories and Schrenk presented Muller with a 50-caliber round he had found in 2008 at the site of his Denmark landing ― this time as a symbol of peace and friendship.

Hans Hermann told Schrenk that when he saw the B17 was badly damaged, he knew its crew posed no threat so he felt no need to shoot them down.

Schrenk, now 96, told NHK World: "It's very easy to hate the enemy. But in this case, like I said, he saved my life. So, it was very important for me to thank him for it. And it's very much a part of the healing process. Some people go through their whole life, never even mentioning what they went through. And I think it made my life a lot richer."

Moved by their story of forgiveness and reconciliation, Devaux got in touch with Schrenk to share his story in the logbook. Unfortunately, Muller died before Devaux could ask him to sign it.

The Log Book Project has given veterans from both sides of the conflict a chance to revisit a painful chapter in their lives and, for some, to finally find closure.

Devaux says the logbook is running out of pages, but he will continue to compile stories online in the hope that history will not repeat itself.