The government presented the package of measures to a panel of experts on Thursday.

One proposal calls for removing the upper income cap for monthly cash payments to parents and extending the payment period, which currently ends when children reach 15, until they graduate from high school.

The government would increase the allowance for each child for parents with at least three children.

Officials said they will study ways to further increase financial support for childbirth, such as considering public health insurance coverage.

The government also plans to implement measures to ease the financial burden of paying for children's higher education.

The plan proposes to expand the eligibility for students to get a reduction or exemption of tuition fees, or receive grant-type scholarships.

Officials also aim to raise benefits for childcare leave so that a family's disposable would not change for up to four weeks even if both parents take leave.

The plan calls for allowing children to attend nursery schools or daycare centers even if their parents do not have jobs.

The government plans to finalize the package by the end of this month, after discussion with the ruling coalition parties.

Japan's mothers welcome draft measures

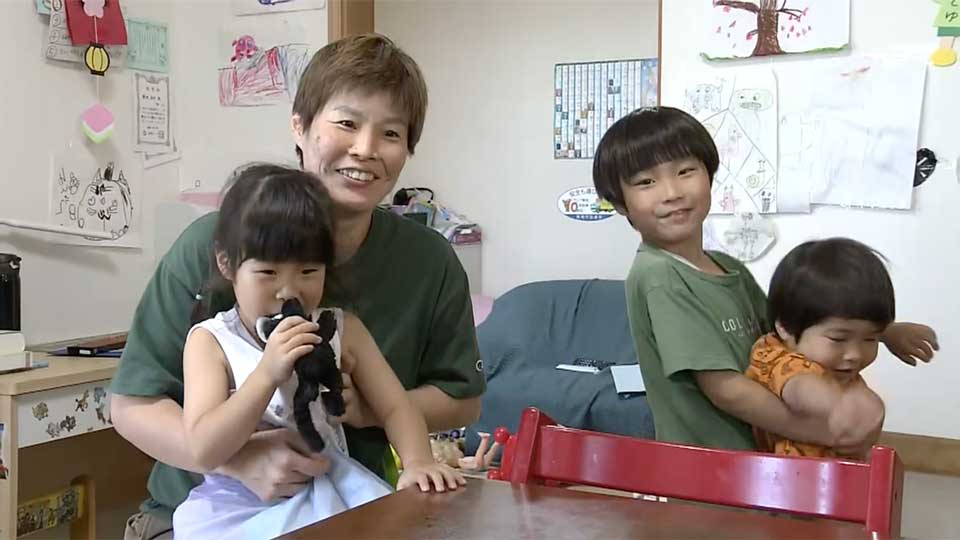

Expanding the allowance would ease the financial burden for many, including the Tokuchi family in Tokyo.

Tokuchi Hiroko and her husband are raising 3 children, from a two-year-old to an elementary school second grader. They currently receive child-rearing benefits for all three children.

If the child-rearing benefits are increased according to the government's plan, the family will receive more for their third child, as well as benefits for all of their children until they finish high school.

"I am grateful for the plan. The financial burden for education has been heavy for us since we have three kids," Tokuchi said.

However, she remains cautious. "I don't know how long the new system will continue. I think it's too risky to depend on such benefits, so we will still economize and build up our savings as well," she said.

The government package also calls for relaxing the criteria for families to use daycare centers. The Children and Families Agency have already started implementing model projects in about 30 municipalities.

One is Tochigi City, where a facility regularly accepts children up to the age of two once or twice a week who usually do not attend daycare.

One mother said she used to have to give up going to see a doctor when she was sick because she had no childcare options. "Having a place to depend on is reassuring for mothers, and helps tremendously," she said.

Some small businesses concerned about costs

But not everyone is welcoming the plan. Some small businesses have expressed concerns.

Eduriko Engineering, a sheet metal manufacturer in Iwate Prefecture, raised wages for its 53 employees in April to keep pace with inflation. Despite facing millions of yen in additional costs, the company plans another pay hike next year.

Company president Kikuchi Kojiro said he is worried that stepped-up measures to deal with Japan's declining birthrate will further increase his company's financial burden.

"I think measures to tackle the declining birthrate are necessary for Japan's population to grow," Kikuchi said.

"I hope the government will take into consideration that small business such as mine are already struggling financially when they advance discussion."

Details of plan's funding to be decided by year-end

To fund the plan, the government aims to secure about 3.5 trillion yen, or 25 billion dollars, annually over the next 3 years.

Prime Minister Kishida Fumio on Thursday stressed that Japan will take "unprecedented" measures to address its falling birthrate "without asking the public to shoulder an additional burden."

The government plans to reform social welfare spending, and establish a new support system by fiscal 2028. Officials said they could temporarily issue special bonds to fund measures until the system is set up, but would not raise taxes.

They will decide on details of how it will be funded by the end of the year.

Officials said the package will increase the Children and Families Agency's annual budget by about 50 percent from its current level of nearly 5 trillion yen. It aims to double the budget by the early 2030s.

Opposition parties, business group show mixed reactions

The opposition Constitutional Democratic Party's Diet affairs chief Azumi Jun criticized the government for making a "mockery" of voters by proposing benefits without saying how they will be funded.

"They are presenting rosy pictures without showing how they can secure as much as 3.5 trillion yen. That's being kind of dishonest with voters," Azumi said.

Baba Nobuyuki, leader of the opposition Nippon Ishin Japan Innovation Party, said that comprehensive measures should be taken instead of ad hoc responses.

Tokura Masakazu, the chairman of the Keidanren, or the Japan Business Federation, said that he appreciates the government's determination to avoid slowing the momentum of wage hikes and domestic investment. He added that he hopes officials will consider social security reforms, including mid- to long-term tax plans, as discussions on measures to tackle the declining birthrate continue.

An expert on social security policies points out that how the government secures the budget for its plan will determine its effectiveness.

Shibata Haruka, Professor at Kyoto University's Graduate School, said it is possible that the way the plan is funded might reduce its impact. "If the incomes of young unmarried people drop, that would make it more difficult for them to get married, or they may hesitate to have their first baby," Shibata said.

He said significantly increasing the budget for children is good, but assessing the plan without details of the new systems is difficult. He suggested the government should be very careful about how it will secure financial resources.

Japan's fertility rate continues to slide to record low

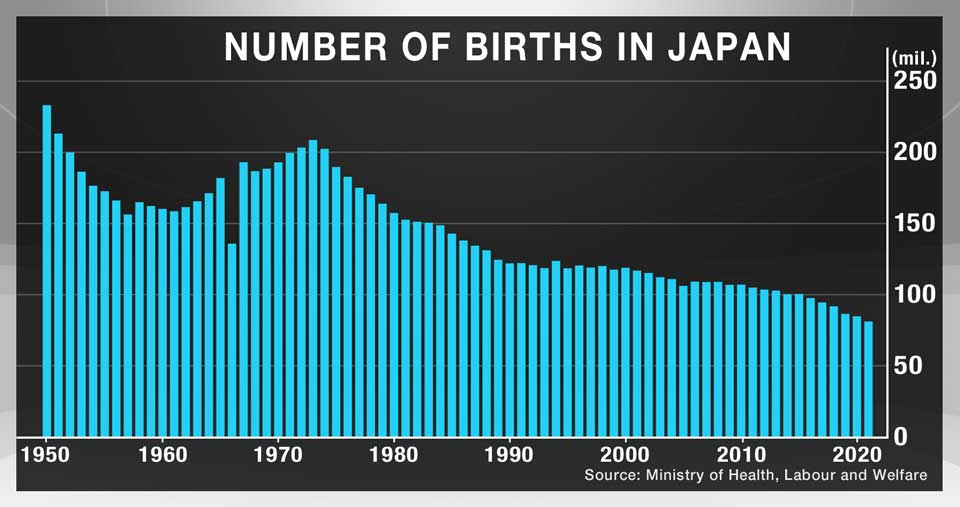

Japan's fertility rate sank to its lowest level in 2022 since record keeping began in 1947.

According to the health ministry's statistics released on Friday, the average number of children born to a Japanese woman in her lifetime was 1.26, decreasing for the 7th straight year.

Among the country's 47 prefectures, Tokyo's fertility rate was the lowest at 1.04, while Okinawa's was the highest at 1.70.

The number of babies born last year was the lowest since 1899, when authorities started tracking that figure.

In 2022, Japan recorded 770,747 births, 40,875 fewer than the year before, and dipping below 800,000 for the first time.

Experts have warned that Japan faces a demographic crisis, as the country's births fall far short of offsetting its deaths. The number of deaths rose to a record-high 1,568,961 in 2022, up 129,105 from the previous year.