For Japan, that creates a conundrum. It has to balance peace ... with protection.

Seeking protection

A working model of a nuclear shelter has been built in the city of Tsukuba, two hours' drive from Tokyo. It is made of reinforced concrete.

"Amid the perceived nuclear threat following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, there is a growing interest in nuclear shelters among Japanese people," says Ikeda Tokihiro, chairman of the Japan Nuclear Shelter Association, the group behind the facility.

The door to the shelter is 20 centimeters thick, to protect against blasts, shockwaves, and radiation.

The structure also has filtering equipment to purify outdoor air that could be contaminated in a nuclear attack.

Ikeda says his organization is fielding many inquiries about this level of protection. "We need nuclear shelters that can protect people in an emergency," he notes.

It's not just the Ukraine invasion that is fueling concern. Russia's President Vladimir Putin is repeatedly raising the threat of nuclear weapons.

In Asia, China is on pace to nearly quadruple its arsenal of nuclear warheads by 2035, according to the Pentagon.

And North Korea, under its leader Kim Jong Un, has increased the frequency of its missile tests.

Japan's unique position

Rising nuclear tensions create a serious dilemma for Japan. Japanese security is dependent on the United States' nuclear umbrella. In fact, Japan, the US, and South Korea plan to discuss the expansion of nuclear deterrence in the region during the Summit.

But Japan is also the only country in the world to suffer a wartime nuclear attack. A strong nuclear disarmament movement reaches into the top levels of government.

Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio is a driving force behind an organization called the International Group of Eminent Persons for a World without Nuclear Weapons. It held its first meeting in Hiroshima last year.

At the group's second meeting, in Tokyo last month, Kishida declared that he wants to send a strong message for a world without nuclear weapons at the G7 Summit.

A delicate balancing act

That message is a key reason this year's G7 host city is Hiroshima.

Japan, as both a victim of the atomic bomb, and a country being protected by such weapons, is expected to present a concrete proposal towards nuclear disarmament.

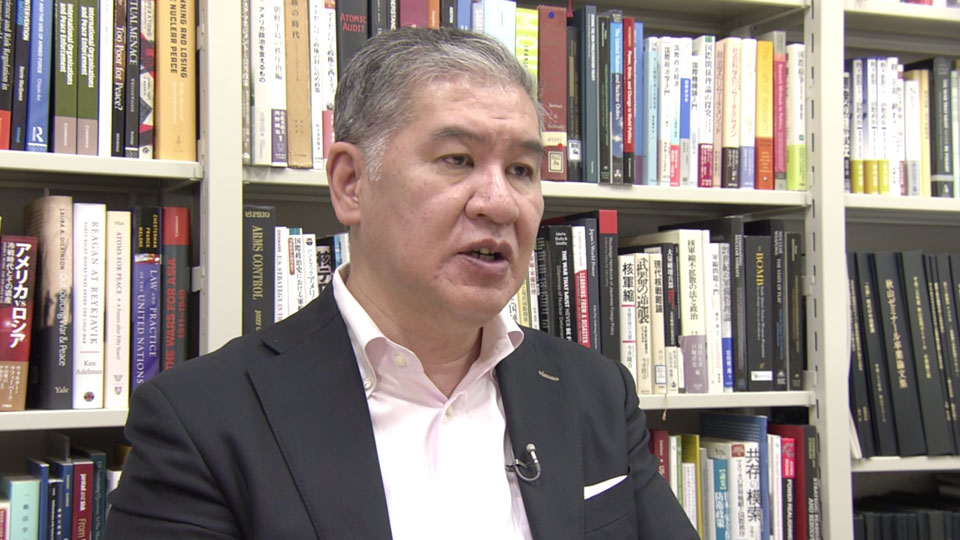

Akiyama Nobumasa, Dean of the School of International and Public Policy at Hitotsubashi University, explains the debate: "We face the risk of the use of nuclear weapons, and also the risk of an increase in the nuclear arsenal in various parts of the world. We definitely have to continue to work on nuclear disarmament. At the same time, we also have to remind the international community that the use of nuclear weapons would have catastrophic consequences for the entire world."

Akiyama says the Japanese government faces a delicate balancing act.

"(Japan) wants to avoid behavior that could undermine US determination, or US commitment, to the extended nuclear deterrence," he notes.

With a push for peace — and a message that G7 countries will stand up against the threat of nuclear weapons — Hiroshima looks set to host a Summit that takes into account its complex setting.