Acquitted by top court

Standing in front of Japan's Supreme Court building in Tokyo on March 24, Linh's defense lawyer, Ishiguro Hiroki, held up a 'not guilty' sign and declared that justice had been served: "The Supreme Court has recognized that the actions of a mother doing her best in a bad situation are not a crime."

More than two years had passed since Linh, a 24-year-old Vietnamese woman, was arrested. Her nightmare had begun when she gave birth alone on a farm to stillborn twins. Linh had wrapped the babies in a towel and placed them inside two cardboard boxes, one within the other.

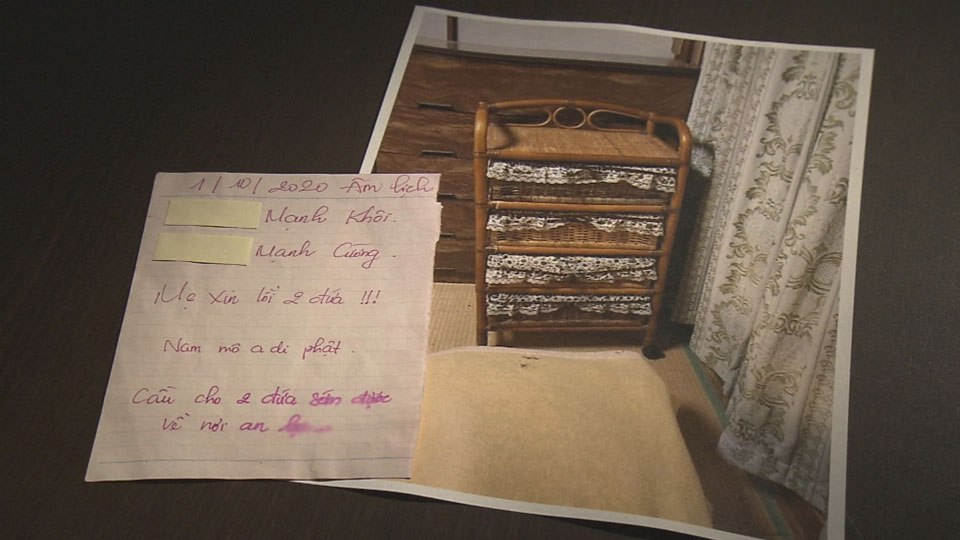

She named her twins Khoi and Cuong, and wrote them a note begging their forgiveness. Then she sealed the boxes with tape and put them on a shelf, before falling asleep. The following day she was transported to a hospital, where she acknowledged the deaths, and was arrested. At first, she didn't understand why.

In July 2021, the Kumamoto District Court ruled Linh was guilty of abandoning the bodies and not fulfilling her obligation to hold a funeral, something the court said that "this clearly hurts general religious feelings of the people."

But in January the following year, the Fukuoka High Court ruled that keeping the bodies in her room for 33 hours did not constitute abandonment and could not have allowed for sufficient time to hold a funeral. Even so, the court found that Linh was guilty of trying to hide the bodies because she put them in boxes and sealed them with tape. The court handed her a three-month prison sentence, suspended for two years.

Linh said she had chosen to use two boxes and sealed them because she felt her babies would be cold and she thought of the boxes as a coffin.

Linh's long legal battle finally came to an end on March 24 when the Supreme Court ruled that although "she created a situation in which it would be difficult for others to find the bodies regarding the location, the way the bodies were wrapped and placed, it did not constitute abandonment." The four judges unanimously found Linh not guilty, overturning the lower court judgements.

Isolated in a foreign country

A major obstacle for Linh's legal defense was her decision to keep the pregnancy secret from her employer and supervisor.

One of the main reasons was financial. She had accumulated more than 11,000 dollars in debts in order to come to Japan. To pay that off, she worked long hours, earning the equivalent of around 900 dollars a month, and sending 750 dollars back to her parents and creditors.

Roughly 18 months after her arrival, she was debt-free and was making some money. That was when she met a fellow Vietnamese trainee online. The relationship led to an unplanned pregnancy, which Linh decided to keep secret so she could keep her job and continue sending money home to her family.

But then tragedy struck. During the busy mandarin harvest season, Linh fell from a tree on the farm.

That night she gave birth to the stillborn twins. They were a month early.

Linh felt completely isolated. She was the only Vietnamese trainee on a farm in a foreign country. She couldn't speak Japanese and didn't know how to get medical assistance.

She says she didn't talk to her employer or supervisor about her situation because she felt she couldn't trust them. One reason for this, she says, was that they had denied her some overtime wages. Contacted by NHK about this, her management organization declined to comment.

Linh says she also heard from a former trainee – and read reports online – that Japanese companies usually sent pregnant trainees home.

Pregnant trainees still penalized

In March 2019, the Organization for Technical Intern Training which oversees Japan's technical intern training scheme, warned companies and supervising organizations that it was illegal to penalize pregnant trainees.

But last December, the Immigration Agency presented the results of a survey of 650 trainees from Vietnam, the Philippines and five other countries that showed one in four of the respondents had been subjected to "inappropriate remarks." This included being told not to get pregnant. One in 20 had signed a contract that illegally stipulated they would not do so.

Another survey found that during a roughly three-year period from November 2017, out of 637 women who got pregnant, less than 2 percent were able to resume their training after childbirth.

Tanaka Masako, a professor at Sophia University who has researched the problems faced by foreign women working in Japan, says: "Organizations are no longer forcibly taking trainees back to the airport, but they are now trying to convince workers to go back to their country and not take their maternity leave." She says some even tell trainees it would be in their best interest to consider an abortion.

"It's a problem created by the basic assumption that technical trainees aren't supposed to have children because we regard them as a cheap, replaceable labor force," she says.

One firm that responded to questions by NHK on the condition of anonymity conceded that "due to the chronic labor shortage, we can't even think of (taking care of) trainees getting pregnant and giving birth."

Tanaka notes the government doesn't compensate companies when their trainees go on maternity leave – an oversight that she says is in urgent need of remedy.

She says there should be more information given to trainees from the outset about pregnancy and contraception. Birth control in Japan is limited, Tanaka says, and emergency contraception pills are only available with a prescription. As a result, Vietnamese trainees buy them online at their own risk.

In the short term, she proposes foreign trainees should be given information systematically on available birth control in Japan during the month of training they receive when arriving in the country."

Story strikes a chord

Linh's story has resonated far beyond the foreigner community. More than 90,000 people from across Japan and the rest of the world signed a petition in support of her case. The majority were women. Linh's team of lawyers furnished the Supreme Court with testimony from 127 people – including medical specialists, religious experts, mothers, and women who have suffered miscarriages – calling for a review of the case.

One of those people was 32-year-old Kumamoto resident Sakamoto Haruka, who has a daughter around the same age Linh's children would have been. In her statement, she talked about how she suffered from morning sickness during pregnancy, and extreme loneliness caused by a hormonal change after childbirth. "If I had given birth alone the first time, I wouldn't have been able to bear it."

Sakamoto wrote a letter in support of Linh because she felt the case "has nothing to do with being a foreigner or Japanese. We need an environment where we can give birth to a new life safely whatever the situation, where every pregnancy can be welcomed by society."

Hasuda Takeshi is a doctor and director of the Jikei Hospital in Kumamoto City, which has a baby hatch where parents can anonymously and safely give up their infants. He says a guilty verdict "would have sent the wrong message" because it would have caused "young woman to fear being arrested, and consider hiding or disposing of their babies' bodies, which could possibly lead to genuinely criminal situations."

Hasuda says Linh's case is a reflection of how society perceives pregnant women in distress: "From the perspective of not only the police who investigate, but also hospital staff, those women can be suspicious, not only for giving birth alone but for not having consulted a doctor."

But he says the verdict hints at a social shift: "This time, the voices of support have overwhelmed the voices of criticism." He notes that Linh's case has helped bring a better understanding of such women within society.

Learning from Linh

As of June last year, there were roughly 330,000 technical interns living in Japan. The government launched the trainee system in 1993 to foster basic technical skills among foreign workers as a way for Japan to contribute to developing countries. Since then, the scheme has frequently come in for criticism, and not just in Japan. In its 2022 Trafficking in Persons report, the US Department of State singled out the trainee system, calling it a "guest-worker program" and noting that the Japanese government had not taken "any measures to hold recruiters and employers accountable for labor trafficking crimes."

On April 10, a government-appointed panel presented a mid-term report recommending the abolition of the system. It said a new scheme should treat trainees as a real workforce and allow them to change workplaces under certain conditions, a choice they currently don't have. The final report is expected to be released this fall.

Suzuki Eriko a professor at Kokushikan Univerisity and recognized specialist of immigration in Japan is skeptical about whether it will engender real change. "It may only amount to change in name, because we don't know if it will fully tackle the cause of human rights or address in any way the issues faced by female workers."

Regardless, Linh's struggle has exposed the isolation endured by many foreign trainees in Japan, especially women, and if her case at least helps to raise awareness about their plight and prevent recurrences then it may not have been in vain.