Desperate to escape the frontlines

Almost every day, Gulagu.net is contacted by Russian soldiers looking to flee. The human rights organization was founded by Vladimir Osechkin, an activist who is wanted by Russian authorities for "anti-government activities."

Osechkin has been the target of assassination attempts, so he is now under round-the-clock police protection. When we headed to the location for our interview, we were met by several police officers and subjected to an hour of meticulous security checks.

Just as we were about to get started, Osechkin's phone rang. It was another Russian soldier, who said he wanted to flee the country the following morning and needed advice on what to do if he got caught. Osechkin said he would talk to a lawyer.

He then spoke to another soldier, who he was helping to fly out of Russia the following day. But there was a problem: the man had nothing to wear except his military uniform.

Osechkin's advice was simple: Buy some new clothes. "Don't try boarding the plane in military uniform," he said.

Gulagu.net has been offering consultations to Russian soldiers about defection and asylum since the start of the invasion of Ukraine. After 300,000 Russian military reservists were mobilized last September, the number of people getting in touch skyrocketed.

Osechkin describes talking to troops on the frontlines who are terrified of dying, or don't want to be complicit in the war. He and his team have so far offered advice to more than 500 soldiers. However, the number they have managed to help escape is far lower: just 10 people so far.

"Most of them get in touch with us just once, as they have to do it on the sly," he says. "They fear that if they get caught, they will be made into an example by being punished or killed. No matter how much I want to, I am unable to help most of them."

Low morale

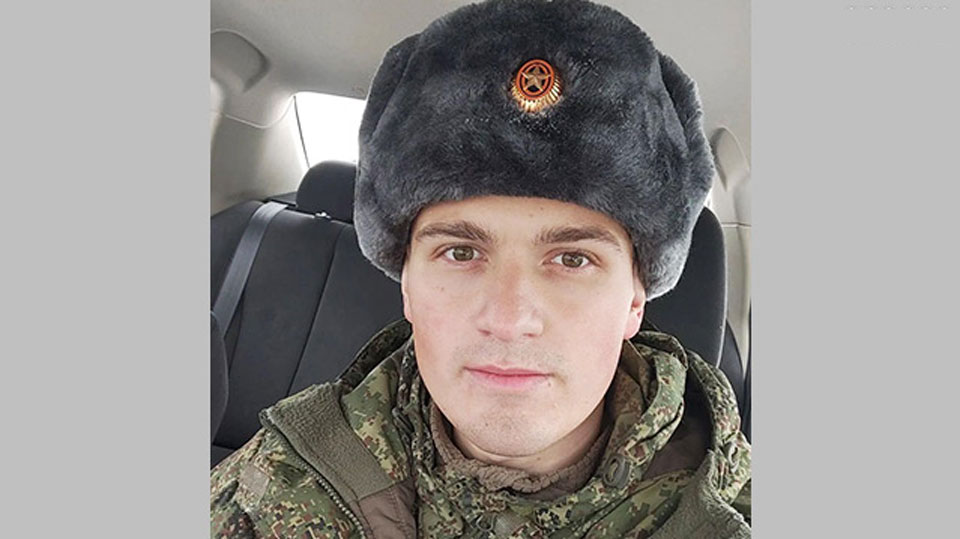

Nikita Chibrin was one of the lucky ones. With Osechkin's help, the former Russian soldier was able to get out . He is now applying for asylum in Spain, where we agreed to speak with us.

We waited for two hours in a hotel lobby. When Chibrin finally appeared, his face was mostly hidden by a hat and upturned coat collar.

Chibrin originally enlisted as a contract soldier in order to earn a steady income and provide for his family. Last year, he was part of one of the main units responsible for the attack on Ukraine's capital, Kyiv.

However, he says their commander kept this mission secret from them until the last moment. When they were dispatched to Belarus at the end of 2021, it was ostensibly for training.

On the night of February 23 last year, the day before the invasion, their commander revealed their actual mission. As Chibrin recalls, he told them: "Tomorrow we will attack Ukraine, and in two or three days we will take control of Kyiv."

Chibrin had never expected to see combat. When he refused, he was threatened with imprisonment, even execution: "I was told that during war, my superior's orders were absolute, and that I would be shot if I didn't obey."

"I was forced to ride in an infantry fighting vehicle. I couldn't open the door from the inside because the handle was broken," he said.

Chibrin says that for most of the soldiers, being sent to the frontlines didn't raise morale. When they came under artillery fire soon after crossing the Ukrainian border, many of them scattered and fled.

He says vehicles and tanks that his unit used were often poorly maintained and frequently broke down. In the vehicle that he rode in, "I couldn't open the door from the inside because the handle was broken."

Despite failing to seize Kyiv, his superiors told the unit they had done well, and successfully repelled Ukrainian forces. They then headed east, where the soldiers went from house to house to steal valuable items and luxury cars.

After witnessing all of this, Chibrin decided to escape. He snuck into a truck bound for Russia. From there, he passed through seven countries before arriving in Spain.

"All I could think about was getting away from the front quickly and going home so I wouldn't have to die," he says. "Many other people like me who wanted to defect have escaped."

Even commanders are resigning

It isn't just rank-and-file troops who are contacting Osechkin's team. Konstantin Yefremov, a high-ranking officer, decided to defect because he disagreed with Putin's justifications for the war.

During an online meeting with Osechkin, Yefremov told him, "If I speak out in Russia, I would be sent back to the front lines, or be dismissed." Osechkin replied, "The most important thing is to protect your testimony and your life. Let's decide how you get out of Russia."

Osechkin helped him plan his route out of Russia and arranged his ticket. After passing through several countries, Yefremov was moved to a country where we were able to interview him.

The former officer describes how his experiences on the frontlines led him to question the pretexts given for the war.

Prior to the invasion, his unit had been conducting exercises on the Crimean Peninsula. Their superiors told them they would be back home in two to three weeks.

Yefremov didn't know that war had broken out until he heard the sudden sound of artillery fire early on the morning of February 24, 2022.

He says there was widespread dysfunction in the chain of command. During one combat operation, he claims that the commanding officers simply disappeared. Over two hundred panicked soldiers started shooting at each other as they scattered and fled. By the time the troops realized they were all on the same side, several hours later, more than 60 had been killed.

Yefremov also says that in some cases, soldiers simply refused to carry out missile attacks that had been ordered by their commanders.

Finding himself unable to support the war effort any longer, he deserted along with a group of officers and six men under his command.

"I felt that I was just a small cog in a barbarous game started by a head of state," he says. "About 10 percent of military personnel are ready to lay down their lives for Putin. Another 40 percent have no opinion, they are just going with the flow ... but the left of more than half of them have nothing but hate and contempt for him."

Yefremov says that officials from the military and Ministry of Defense don't believe the justifications for the invasion, either: "No one is really sure why we are fighting in Ukraine."

"I feel a strong sense of shame and guilt towards the Ukrainian people," he says. "All of us, including myself, must take responsibility for causing so much pain and suffering to innocent people. We must end this war."

A former Wagner commander escapes

Mercenaries from the private military company Wagner Group have also been getting in touch with Gulagu.net.

Wagner, whose existence was only officially acknowledged by the Russian government last November, is believed to have sent as many as 50,000 soldiers to Ukraine. Many were recruited from Russian prisons, where inmates have been offered amnesty in exchange for fighting.

When we met Osechkin last December, he was speaking with Andrei Medvedev. The former Wagner commander was hoping to flee, and was looking for a place where he could cross the Russian border.

"The FSB is searching for me right now," he said, referring to Russia's federal security service. "If I'm caught, they'll hand me over to Wagner, who will 'eliminate’ me."

That was the last Osechkin heard from him. About a week later, on December 15, he received word that Medvedev had been captured by Wagner.

However, on January 13 this year, the former mercenary was able to escape Russia.

Speaking from Norway, where he has applied for asylum, he told Osechkin about the nerve-wracking experience: "I went over a fence, through a forest, and found myself in front of a lake. That's when I noticed Russian border guards running toward me from about 150 meters away.

"I heard two shots fired nearby, so I destroyed my cell phone and threw it into the woods. I could see the lights of houses in the distance. The lake wasn't completely frozen, but I ran across it, toward those houses. The border guards were scared to chase after me, so they sent their dogs instead. I just kept running and running."

Executions used to enforce discipline

Medvedev had signed up with Wagner last July and was sent to Bakhmut in eastern Ukraine, the scene of fierce fighting. He says his orders were to "keep advancing while you're still alive."

He was forced to fight for two days without sleep or even drinking water. Meanwhile, Wagner was conducting frequent executions behind the scenes.

Wagner's contract states that personnel who refuse or fail to carry out orders "may be 'tried’ in accordance with wartime law." According to Medvedev, "tried" means shot dead. He says such "trials" were common, and served as a warning to others.

"Executions are carried out by a Wagner security department called 'Myod,'" he explains. "Each time a new batch of recruits arrives, a combatant who has committed some kind of disciplinary offense is shot dead by this department."

He says he knew of 10 such executions, and had personally witnessed two. One of the victims was killed for trying to escape, the other for being drunk.

"The purpose is to instill fear in newcomers and make sure they don't consider doing anything that might interfere with carrying out orders," he says. "The body is buried on the spot and the individual is labeled as 'missing.' This is to eliminate the need to pay death compensation."

Testimonies as evidence of war crimes

As he helps Russian soldiers flee, Osechkin also collects their testimonies. He is providing these to Ukrainian authorities, the United Nations, and the International Court of Justice, along with internal documents. He says these could eventually be used to help prove Russia's war crimes.

"I believe this is an illegal and unjust war," Osechkin says. "Putin is a dictator who sees his soldiers as nothing more than an assault force operating in the midst of madness. And he lets them die like dogs. It's a real-life nightmare, worse than any horror movie."

Despite intense pressure from Russian security authorities, his team keeps doing all it can to gather evidence for a possible future trial.

"This is our duty as Russian citizens," he says, "as human beings."