On the day of the announcement, Prime Minister Kishida Fumio appeared eager to set an example. He spoke to reporters without a face covering, flanked by an equally bare-faced security detail.

"From now on, I will be without a mask more frequently," Kishida declared.

Reluctance to change

On the streets of Tokyo, it was a different story, as a sea of masked-up workers, students, shoppers and other locals emerged from trains and buses across the city.

One woman said she wasn't doing it for herself so much as for those around her. "I have to speak with people all the time for work," she said. "I'm still worried about making someone sick."

Others are anxious they'll be judged. "I want to take mine off, but I'm concerned about what other people will think," said an office worker.

Japan has never had a mask mandate. The government only requested that people wear them in certain situations. Most complied without question.

Early in the pandemic, experts agreed that it was this compliance that helped Japan curb the spread of the virus. The issue now is convincing people it's okay to take their masks off.

Last month, an NHK opinion poll asked more than 1,200 people how the change in guidance would affect their behavior. Roughly half said it would make no difference; they would continue to wear masks. Thirty-eight percent said they would wear them less often. And just 6 percent said they wouldn't use them at all.

A complex situation

There are several reasons for the stubborn resistance to change. One factor, experts say, is that as long as the majority of people continue to wear masks, many others will feel pressure to conform.

Another consideration, albeit a temporary one, is that even before the pandemic, Japanese people used masks to protect themselves against flu and hay fever during winter and spring.

Professor Yamaguchi K. Masami, an expert on psychology at Chuo University, says that many younger women are now so accustomed to going out in public with masks that they may now feel too self-conscious to remove them.

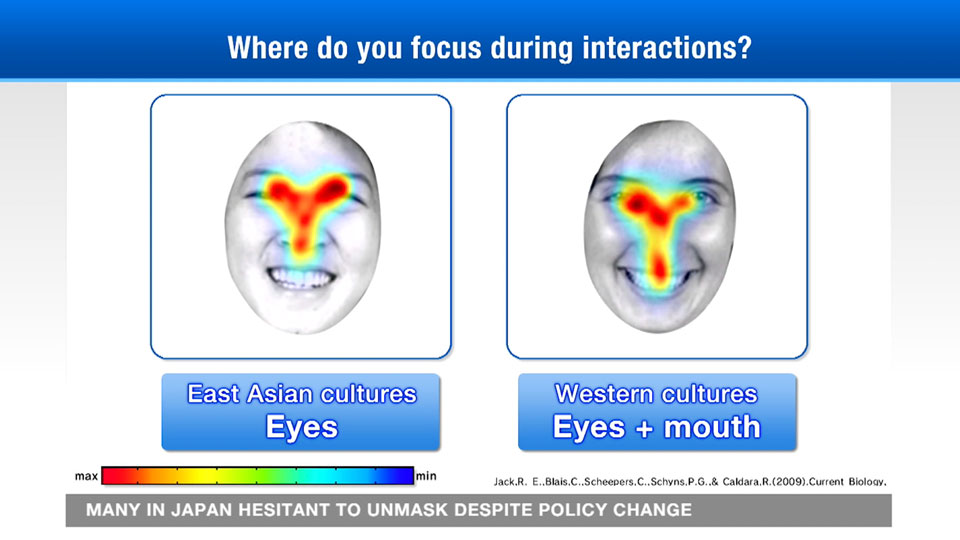

Yamaguchi refers to a study by British and Canadian researchers that found when people in East Asian countries communicate through facial expressions, they do so largely with their eyes, meaning it’s less important to unmask.

"When Japanese people are reading facial expressions, they pay more attention to the eyes, so it doesn't matter if the mouth is hidden," she says. "That's why masks are not as big a problem for communication. People in Europe and the US, on the other hand, tend to be more worried about masks, because masks make it harder for them to read facial expressions."

Different industries, different guidelines

The Japanese Cabinet Office has mask guidelines for almost 200 industries, and has reviewed nearly all of them.

The guidelines for around 150 of those industries, including hotels, pro-baseball, and amusement parks, say industry groups will leave it up to businesses to decide their own rules on mask-wearing.

The guidelines for a further 19 industries, including postal services, hairdressing and beauty treatments, and classical music, say industry bodies will request that businesses ask their employees to keep wearing masks.

And for another 16 industries, such as drugstores, professional basketball, and professional golf, employees and visitors alike will be asked to mask.

When it comes to public transportation, the government recommends that people continue to mask up on crowded trains, especially during rush hour. But it says face coverings are not needed for shinkansen bullet trains and other forms of transportation where almost all passengers have a seat.

The health ministry says it will continue to advise that people use masks in two other situations — when visiting a doctor, and when visiting medical institutions or elderly care facilities with people who are at high risk of developing severe COVID-19.