Some find even basic Japanese difficult

Kosuke is a 19 year old living in eastern Japan. He rarely attended school after the second grade. Although he can read, he is unable to properly write hiragana. All he can manage to write in kanji are his name and address. He can't do multiplication or division.

Last year, Kosuke took up a part-time job in the delivery business. He says he was scolded by his superior because he couldn't write delivery reports.

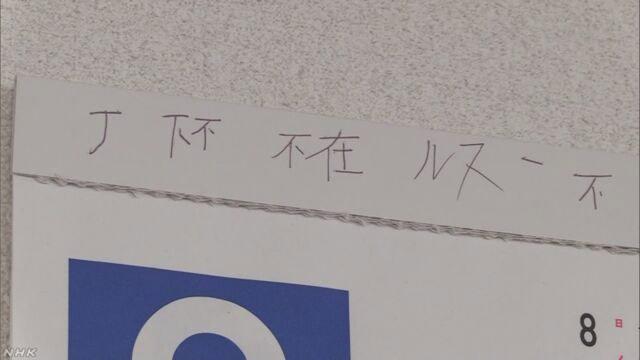

Some paper in his home shows how hard he practiced to write kanji characters needed to fill in memos for people who were not home to receive his deliveries.

But Kosuke quit his job in about a month, as it made him increasingly uncomfortable.

Kosuke and his brother were raised by their mother. She moved from one part-time job to another to look after them, and now lives on welfare, as she cannot work due to multiple illnesses.

Kosuke was regularly beaten by his brother, who is 6 years older. The stress caused by poverty and abuse made him lose his will to go to school.

At first, teachers and officials from his municipality visited his home and tried to encourage him to go to school. But they gradually stopped.

Kosuke says he can't think about his future. He grew up without a proper education, and he is now at a loss over how to go on living.

"Education opportunities are not equal"

Hitomi, a 21 year old living in Osaka, lacks self-esteem because she didn't receive a compulsory education.

When Hitomi was in elementary school, her mother, who was raising her alone, suffered a stroke. Hitomi started missing school to look after her and help her do the chores.

When she was in the 4th grade, they moved to another city due to debt. Her mother failed to take procedures to transfer Hitomi to another school, and she has never attended since then.

Hitomi says she has nothing to write on her resume. She says she feels like an outcast, and it makes her miserable.

Hitomi also faces problems in various areas of her life due to the lack of education. She is interested in fashion and beauty, like other women her age, but she has not visited a hair salon for a long time. She says she is afraid of conversing with the stylist as she doesn't want to open up about herself.

When she goes shopping, Hitomi always uses a calculator to check the money she needs before going to the cashier. She doesn't want others to see her in a flurry over not having enough money.

Hitomi avoids interacting with people as much as possible, and doesn't have any friends her age.

She studied kanji on her own, using a dictionary made for elementary school children. Using what she learned, she wrote, "Why is it so difficult to do anything without a compulsory education? I don't think educational opportunities are equal."

Educational poverty spreading

To get a clearer picture of young people suffering from a lack of education, NHK questioned officials in charge of helping the needy find jobs. Surveys were sent to such officials at about 800 municipal facilities nationwide, and 40 percent responded.

The results show that 597 young people who came to receive assistance had missed a compulsory education. 78 of them said they find it difficult to write and read, and 69 don't know how to do math. 208 said they have trouble interacting with others. Many also said they lack self-esteem, suggesting that a lack of education has an adverse psychological impact.

Asked why they failed to attend school, 101 said they were bullied. The same number of people gave a disability as their reason, and 71 said it was due to illness of one or both parents. 67 answered abuse or lack of understanding by their parents, and 51 responded that it was due to poverty. This shows that the family environment is a major contributing factor in a lack of education.

The government last conducted a survey on the Japanese literacy rate in 1955. Since then, officials have believed most Japanese have no trouble reading and writing.

But a census in 2010 found that more than 120 thousand people had failed to finish elementary school. About 20,000 were below the age of 40. No further details are available, but the figure likely includes people like Kosuke and Hitomi.

Most of the people I interviewed appeared to keep a distance from society. A lack of education doesn't result only in inconveniences in everyday life. Having no academic record makes it difficult for people to land jobs and function as members of society, depriving them of the power to lead productive lives.

Municipality Efforts

To prevent educational poverty, the city of Fukuyama in Hiroshima Prefecture is coordinating the efforts of the welfare division and the board of education.

The 2 sides now share information about families on welfare and single-parent families, and on children who are not attending school.

They created a list of families with children who require assistance, and welfare officials made visits to them. They provide support, such as waking children up in the morning and seeing them off to school, if parents are unable to do so due to illness and other reasons.

Fukuyama City currently provides such support to 71 children, but it plans to increase its staff to offer more assistance.

Night schools help take the first step

Night schools are offering help to those who could not receive a basic education.

In the past, students at night schools were mostly elderly people who could not attend school in the confusion after the war, and foreign residents. Recently, however, the number of young students is said to be increasing.

Hitomi, who could not finish elementary school, began attending night school in Osaka 3 years ago at the age of 19.

Since then, her academic ability has improved dramatically. At first, she could bearly recite the multiplication table, but now, she can solve complicated math problems.

She has also become able to express herself through writing. By engaging in conversation with classmates of various ages, the way she interacts with others has changed as well.

During an interview, she revealed that she wanted to visit the elementary school she attended until the fourth grade. As she approached it and saw children practicing for an athletic event, she appeared to be recalling the past. Hitomi said memories of those days used to torment and keep her awake at night. This was the first time she was able to visit her old school.

"Something has changed, although I don't know exactly what. Attending night school has given me courage, so that might be it," she says.

Measures to prevent educational poverty

To support those who haven't received an education and those at risk of not receiving one, it's important to create an educational safety net that can support everyone.

In 2017, the government enacted a law to guarantee all citizens a basic education.

Following this move, authorities have also instructed regional governments to set up at least one publicly-run night school, like the one Hitomi is attending, in each prefecture. At the moment, only 8 out of 47 prefectures in Japan have such schools.

According to the Educational Ministry's survey, 6 prefectures, including Kochi and Kumamoto, and 74 municipalities are considering building night schools. Support from the central government is crucial in having other regions take part in the initiative.

It's also necessary to provide adults with free study support if they can't attend evening classes due to work or because they have small children.

It is not easy for people who have trouble reading or writing to find the assistance they require. It will be helpful to provide information about learning opportunities when they come to job placement centers looking for work.

Sophia University Professor Akira Sakai says that the most important thing is for authorities to understand the severity of the situation.

He says, "The country's public education system must be reexamined to provide all children with educational opportunities guaranteed in the Constitution. Coordination between the government and the private sector is also indispensable. Until now, authorities have focused on providing education to children who come to school, but they must also consider offering other ways to learn."

To learn is to live your own life

Hitomi says she had been harboring a desire to study again since she saw a poster of a night school in a street. She agreed to be interviewed by NHK in the hopes that "people in a similar situation who are struggling will find a place to study again."

Hitomi has taken a step forward, as have others who were interviewed for this story. Hearing their stories made me realize that learning is crucial for us to live our lives with dignity.

A place for learning isn't just somewhere to study reading, writing, and math. It's also a place to meet friends and teachers who will provide lifelong support. And it's the starting point of a journey to fulfill dreams and ambitions. I will continue to investigate what is being done to ensure everyone can enjoy the right to an education.