Black Summer

Steve the koala lost his mother and suffered severe burns in the Black Summer wildfires that swept Australia in 2019 and 2020. He was one of 28 koalas rescued from Kangaroo Island, off the coast of South Australia, after flames reduced almost half the land mass to charred embers.

Black Summer was one of the most devastating wildfire seasons in recorded Australian history. The fires destroyed thousands of homes and, according to one estimate, killed or displaced billions of animals. The smoke enveloped New Zealand and eventually traveled all the way to South America.

The fires were especially devastating for Kangaroo Island, an area famous for its biodiversity. Up to 80 percent of the estimated 50,000 koalas on the island died. Other endemic species, such as the Kangaroo Island dunnart and glossy black cockatoo, also suffered heavy losses.

"In our 25-year history here, we've had more little fires in the district than I can keep count," says Jim Geddes, who runs koala-spotting tours at the island's Hanson Bay Wildlife Sanctuary. "But this last one was much bigger than anything we have seen before."

The fires were followed by long periods of heavy rain that spurred a rapid regeneration of vegetation across the island. Three years on, lush green foliage has swallowed up the burnt-out trunks and other evidence of the inferno, and the koala population is mounting a recovery.

But the same rain that revived landscapes across Australia now poses a threat in other parts of the country.

Flooding

Sleepy Burrows Wombat Sanctuary sits in the gully-lined hills north of the capital, Canberra. When it rains so heavily, so often, even this steep terrain is transformed into a dangerous flood zone as torrents of water churn through the area. Sanctuary manager Donna Stepan says frequent downpours this year have posed a constant threat to the animals.

"It's normally once a year the causeway is bad enough that you can't get across," she says. "But this year, it's now been 14 times."

Wombats, close relatives of koalas, live in underground burrows that provide safety from fire but can turn into deathtraps during floods.

Stepan says 10 wild wombats used to come at night to feed, but now she only sees three. She thinks the others have probably drowned.

She tries to flood-proof the sanctuary, but says her efforts often feel futile.

"You hear, 'Oh, it's going to happen again next week with the rain.' And then that happens. And then, 'It’s going to happen the next week,' and it's just …" her voice trails off.

The political context

When these floods clear, long-term solutions to the threats facing the country will still be urgently needed. But this can only happen with public pressure.

"Governments respond to how people vote," says Dr. Thomas Newsome, who studies threats to biodiversity at the University of Sydney. "And until the broader public really prioritize our native ecosystems and our native animals, it's unlikely that the state or federal governments are going to act."

In that respect, Newsome sees cause for hope.

"When there are surveys done of what people are prioritizing, or what people think are the major issues right now, climate change keeps coming up now, time and time again," he says.

During Black Summer, Sydney was blanketed with thick smoke for days. Now, homes in the outer suburbs have been repeatedly inundated by floods. As the effects of a destabilized climate become harder to ignore, more people are demanding change.

That's where Steve the koala can help.

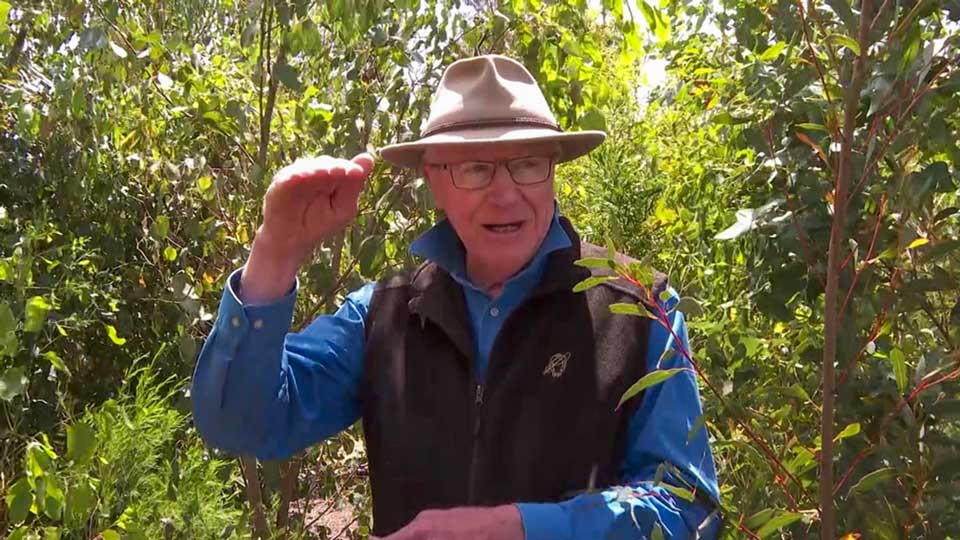

"His future is now as an ambassador," says Dr. Ian Hough, research manager at Koala Life, who led the Kangaroo Island koala rescue during Black Summer and cares for the orphaned survivors at Cleland Wildlife Park on the outskirts of Adelaide.

"There's something about getting up close and holding a koala, and that will stay with you forever. And they take that away and, hopefully, that will engender some useful environmental activity that will help the forest, and the koala, and the rest of us."

With most mainland koala communities afflicted by disease as much as natural disaster, Dr. Hough's Kangaroo Island survivors -- and now their own joeys -- have become a disease-free insurance population for their endangered cousins across the country. It's a new chapter in the story of human mismanagement of the land and its wildlife since European settlement in the 18th century. After all, koalas were only introduced to Kangaroo Island in the 1920s after being hunted close to extinction on the mainland for their fur.

"It's tragic that it took such a horrible event," Hough says of the Black Summer fires. "But out of that there is definitely hope, and cause for optimism".

And he says Steve appears content in his new role. "As long as he has plenty of food then he doesn't care about anything else."