Mali was a colony of France until 1960. The two countries maintained a strong bond in the decades that followed, but relations appear to have soured over the past few years.

And now, Mali appears to be turning toward Russia.

In March, the West African nation abstained from voting on a UN resolution condemning the invasion of Ukraine.

We saw evidence of the shift firsthand on a recent visit to Mali, a country that remains under military rule.

In the capital, Bamako, roadside vendors sell the flag of their own country, but also Russia's. And tellingly, authorities have banned French radio and television.

'Pro-Russia' influencers gain support

Public distrust of France has risen in tandem with a worsening security environment. Over the past decade, Jihadist extremists have grown into a formidable movement.

France started sending troops to help in 2013, but with little impact. Mali's military then sought to take advantage of the instability by staging coups. First in 2020, and again in 2021.

And in August this year, the French withdrew, leaving a void that Russia has sought to fill. Moscow has since sent helicopters and other military gear to combat the extremists.

Not a few people have welcomed the change.

"France is only trying to impose its policies on Mali, and hasn't accepted our will," says Drissa Meminta, a lawyer and pro-Moscow social influencer.

"We had walked along together, but we gained nothing. With Russia, however, we can build a win-win relationship."

Meminta has nearly 120,000 followers on social media. He started urging people to get behind Russia about three years ago, both online and at in-person gatherings.

On the day we meet, nearly 500 people are watching one of his streams. He defends Russia's actions, and his words prompt a steady stream of likes.

Wagner Group makes inroads

The Wagner Group, a Russian private military firm whose founder is believed to be close to President Vladimir Putin, is said to be front and center in the push to strengthen ties with Mali.

Wagner mercenaries are thought to have been active in numerous conflict zones, including Syria and Ukraine. The organization is suspected of a string of human rights abuses, including summary executions and torture.

The Swedish Defence Research Agency says the Wagner Group is active in at least six African nations. Many are ruled by authoritarian governments.

But, when it comes to containing extremism in Mali, the group has failed. In fact, international NGOs set up to monitor conflicts say the attacks have only intensified.

A former parliament member, close to the ousted president worried

"People firmly believe only Russia can offer solutions, and that Wagner will swiftly eradicate the extremists. But that's wrong," says Bocari Sagara, a former parliament member, close to the ousted president.

Sagara is worried about Mali becoming dependent on Russia. And he's especially wary of the public's vulnerability to misinformation.

"Many people in Mali don't have proper access to education, and it's difficult for them to understand what's really happening now," he says. "They tend to believe everything they hear."

Sagara insists the path to a better future must be free from military campaigns.

"The true solution is not to take up arms and kill each other, but to understand why extremists are growing in number," he says.

"Ultimately, we have to work step-by-step to turn Mali into a country where young people are granted educational and employment opportunities."

Burkina Faso next

A strikingly similar situation is playing out across the border in Burkina Faso. Like Mali, this is a former French colony that's regularly rocked by extremist attacks. The military seized power there in January.

And observers say Russia is seizing the moment.

People recently held a series of demonstrations in the capital, Ouagadougou, calling on the country's leaders to cut ties with France. Footage showed some carrying Russian flags.

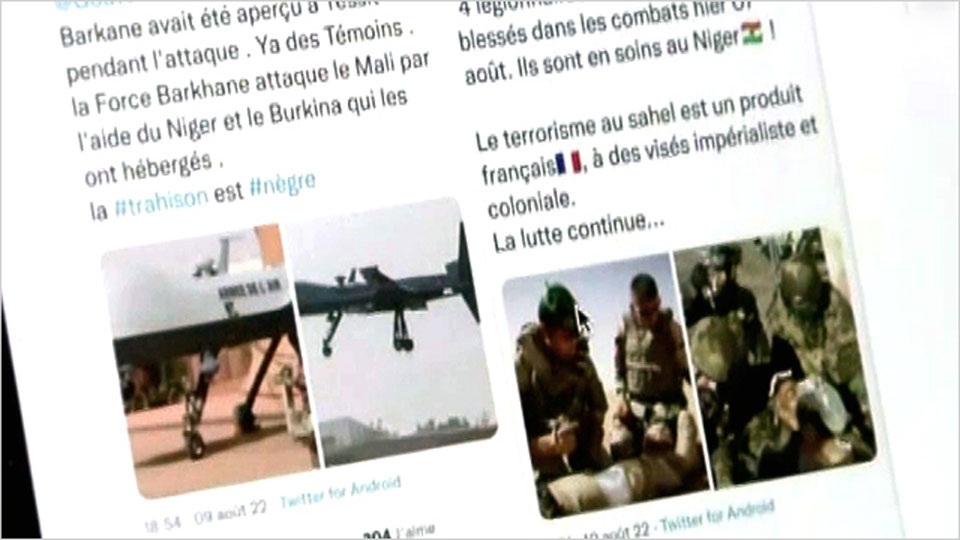

The shift appears to be fueled by social media. Accounts with tens of thousands of followers churn out posts criticizing France and calling for stronger ties with Moscow.

We visit a pro-Russian group in Burkina Faso to learn more. We're welcomed by one member whose T-shirt features the flags of both countries. Another man even sings a song praising Russia.

They say they've gained 10,000 supporters in the past six months. Your correspondent is told the group's activities are entirely funded by donations, though the members we meet deny receiving any direct support from Russia.

Finding hope on social media

Much of the group's success is down to a sense of desperation in Burkina Faso.

"All we want is a country that helps free ours from terrorists. I hope Russia will save us," says Sibiri Bamogo, who fled to the capital after extremists attacked his hometown in the north three years ago. He says they killed his uncle, and he cannot return home.

Bamogo says he found hope on social media. And he shows us a video clip with a photo of Putin and Macron. The narrator says, "France is providing weapons to extremists and is being criticized. Putin is ready to help you."

To us, it's simply ridiculous. But we can't say that to Bamogo -- whose story illustrates just how easily pro-Russian narratives can resonate with the vulnerable.

And there are many vulnerable people. Bamogo is one of about 1.9 million who have been internally displaced in Burkina Faso.

Concerns rise over misinformation

As pro-Russian content proliferates, so do concerns about misinformation. Officials at FasoCheck, a local fact-checking organization, say posts like the one that struck a chord with Bamogo are commonplace.

They show us some other examples. One from August says France worked with extremists to attack civilians in Mali, but features an image the French military used five years ago for public relations.

And a video claims to show French forces supplying weapons to extremists. In reality, the footage is of an NGO using a helicopter in a conservation area.

"These types of posts are meant to spread false rumors about France, to arouse hatred of the country," says one official at FasoCheck. "And they're used to meet Russia's diplomatic purposes."

Mark Duerksen of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies even suggests key members of the Russian government could be involved. "The campaign to spread misinformation is systematic, with various layers of intermediaries involved," he says.

"Russian officials are helping to disguise the links between the campaign and the Kremlin using increasingly shrewd tactics."

'Grabbing onto what we can'

Pro-Russian sentiment is taking root in Burkina Faso, and attention is focused on how close the government decides to get with Moscow.

"Some people compare Russia with the West, but we don't want to hear from those who don't try to help us," says Foreign Minister Olivia Rouamba. "To pull ourselves out of this tight spot, we have no choice but to grab at twigs -- however thorny."