'Season of turmoil'

The regime of former Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos ran from 1965 to 1986, including nine years of martial law starting September 21, 1972. Marcos said his aim was to stamp out communism.

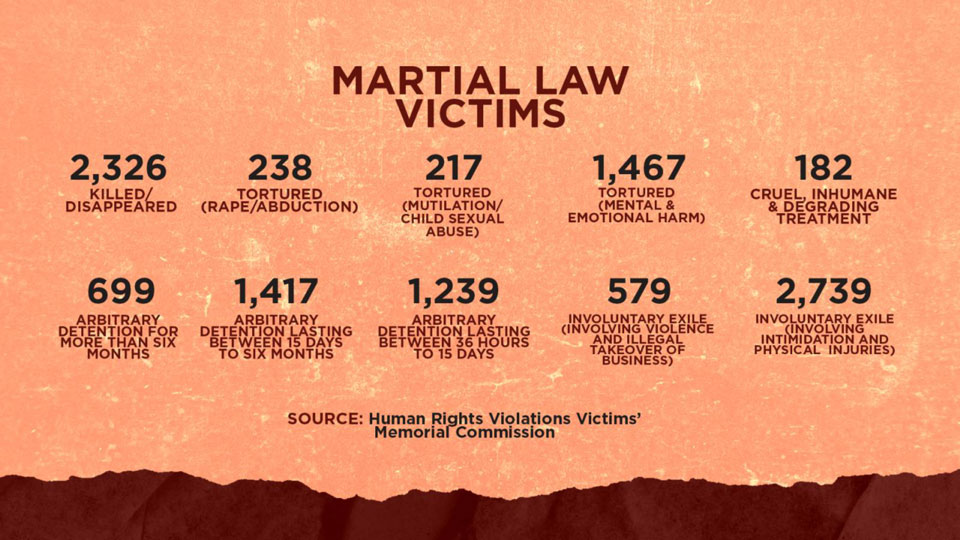

But the years of military rule saw state forces commit widespread human rights violations against government critics and ordinary citizens. Official Philippine data shows at least 2,326 people were killed or disappeared, 1,922 were tortured and 3,355 were illegally detained.

Amnesty International's figures are much higher. Over the same period, it has documented cases of imprisonment involving 70,000 people, 34,000 cases of torture, and 3,240 murders in the form of extrajudicial killings.

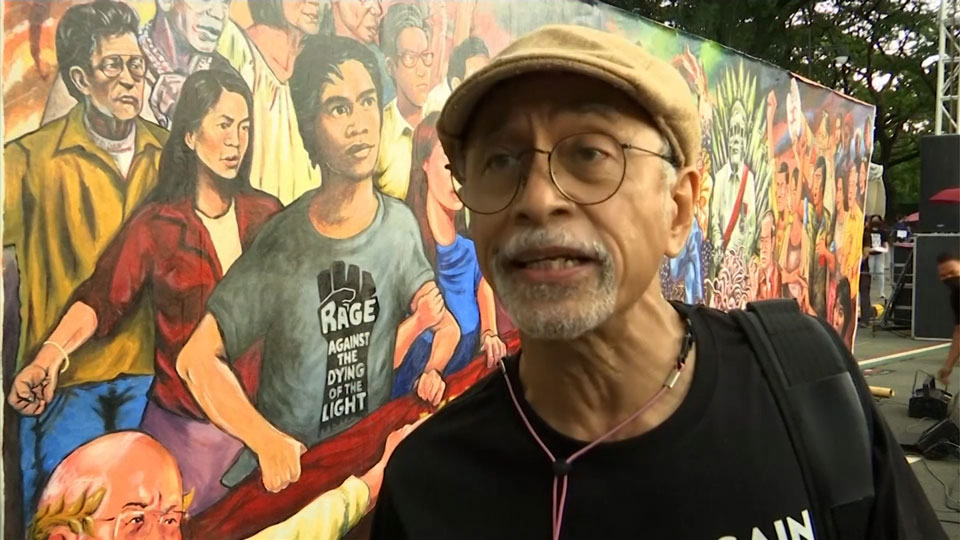

"It was a season of turmoil," says 70-year-old torture victim Bonifacio Ilagan. "Everyone who as much as dissented against the president was considered an enemy of the state. It was martial law, there were no niceties, no arrest warrants."

Torture and abuse

During his early 20s, Bonifacio was a student activist. He says his heart raged with a fire that surpassed his age: his love for his country. He spent most of his youth at rallies, raising his fist in defiance against all forms of injustice.

But in April 1974, the authorities caught up with him. An intelligence unit raided the safe house where he and his friends were printing newspapers critical of the government. They were arrested on the spot.

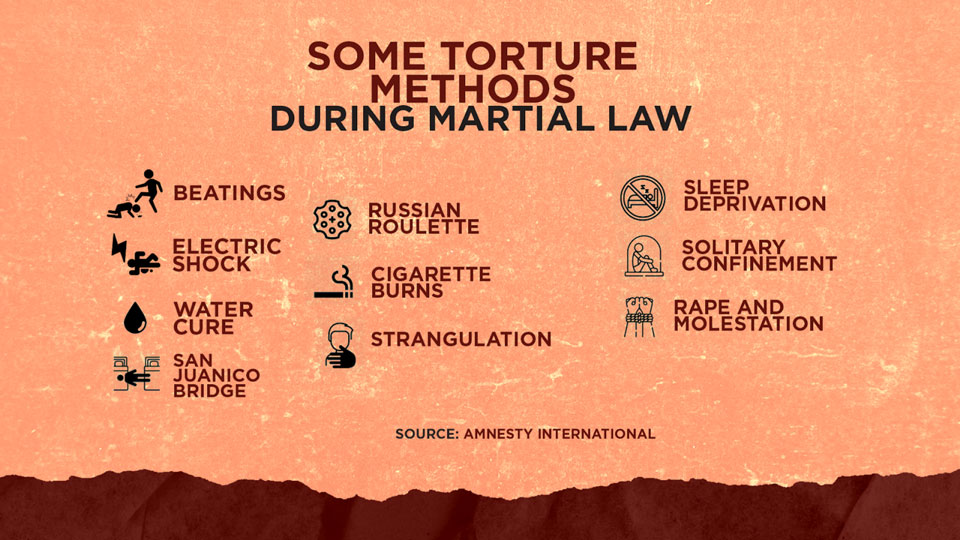

Bonifacio was taken to Camp Crame, now the headquarters of the Philippine National Police in Manila. Inside his prison cell, he was subjected to unspeakable cruelty. His captors inserted a stick inside his penis, forcing him to name other activists he knew. Bullets were placed between his fingers and his hands were squeezed so tight, he could feel his bones breaking.

For Bonifacio, there were only two kinds of days inside detention: bad and terrible. Sometimes, on a whim, his captors burned the soles of his feet with a clothing iron. Interrogators would force him to lie between two beds with only his head and feet supporting him. They would ask questions and punched his stomach if he remained silent.

The torture method was called the "San Juanico Bridge," named after a 2.16-kilometer bridge the late Marcos built as a gift for his wife Imelda for Valentine's Day. What many considered a symbol of romance became entwined with Bonifacio's darkest days.

"The torture lasted for months. And there were many forms," Bonifacio recalls. "I could no longer take it. One day, I urinated blood."

Bonifacio was held captive for two years, enduring excruciating psychological, physical and emotional abuse. But the most painful episode took place outside his prison cell.

In 1977, nearly a year after his release, his younger sister Rizalina vanished. Like Bonifacio, she was also an activist. Her disappearance became a fresh nightmare for Bonifacio, who spent many years in a fruitless search. No trace of Rizalina has ever been found.

Concerns over historical revisionism

Fifty years after the declaration of martial law in the Philippines, the dictator's son Ferdinand Marcos Jr. is now the country's top official. He was elected in a landslide victory in June.

The younger Marcos has always expressed respect and admiration for his father in speeches and interviews. He has urged Filipinos to learn from what he hails as the late president's values. He denies there was a dictatorship.

"What my father wanted to do was something that was honorable, something that was noble, and that was of service to his country and his people," Marcos Jr. says.

In an interview days before he addressed the United Nations General Assembly in September, the president insisted it is inaccurate to call his father a dictator because government policies during his term were drafted only after consulting stakeholders.

Marcos Jr. also defended his father's decision to declare martial law, claiming the proclamation was necessary to counter communism.

In August, a film depicting the last three days of the Marcos administration was released in cinemas around the world. It was funded by the elder sister of Marcos Jr.

The movie rewrites history in depicting the Marcos family as heroes who made the difficult decision to leave behind their lives in the Philippines to prevent further bloodshed in anti-government protests. In reality, Ferdinand Marcos was overthrown in a people's uprising, and he and his family were driven into exile.

Moves to rehabilitate the former president's reputation have angered some Filipinos, especially victims like Bonifacio.

He warns of the dangers of historical revisionism, not only for the Philippines but also globally. He says if we allow those in power to erase dark chapters of history, "peoples of the world will continue to suffer fascism and tyranny," and abusers can escape accountability.

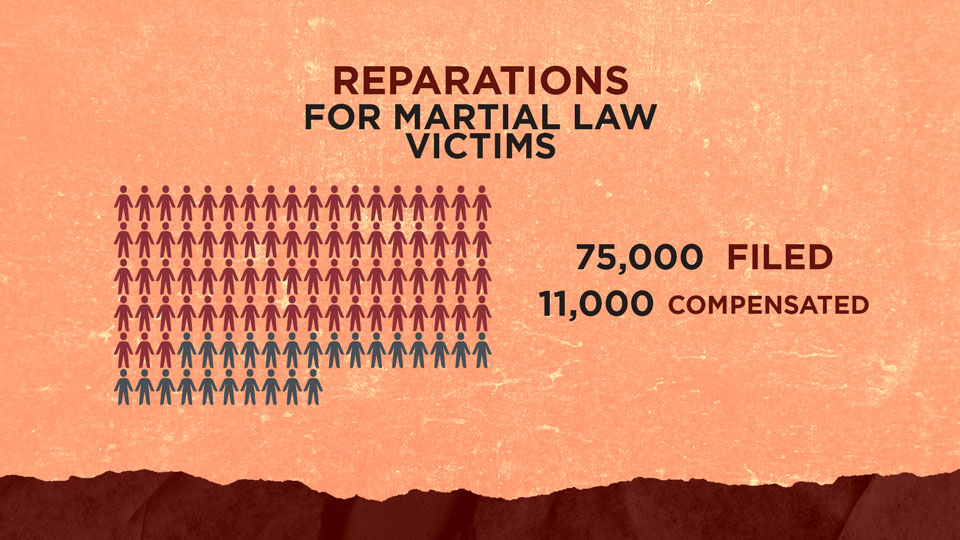

Since his imprisonment and torture at Camp Crame, Bonifacio has been helping others who suffered as he did. Efforts to sue the government for compensation are ongoing. So far, 75,000 victims have filed complaints, but less than 20 percent have received reparations.

Preserving real history

In the face of continuing attempts to whitewash the martial law era, people who refuse to forget are challenging misinformation, including what circulates on social media.

One of them is 20-year-old Karl Patrick Suyat. He is a co-founder of Project Gunita, a citizen-led online archive. The project was launched a day after Marcos Jr won the presidency, out of fear that historical records would be destroyed, revised or forgotten.

As a son of an activist and grandson of a political detainee, Suyat is dedicated to preserving his family's memory and the truth about martial law.

"They use film, they use social media, to distort history. We're going to fight them on the same platforms and on other platforms, where they will not expect us to fight their lies," Suyat says.

Project Gunita's materials are mostly sourced from collectors who have donated or sold archival materials from the era. The group's digital archive displays PDF copies of books, newspapers, magazines and pamphlets.

Bonifacio and others welcome the initiative. "There are young Filipinos who don't know much about history, but who want to know," he says. "As long as there are Filipinos their age, who are willing to know, and to carry the torch, then all hope is not lost."