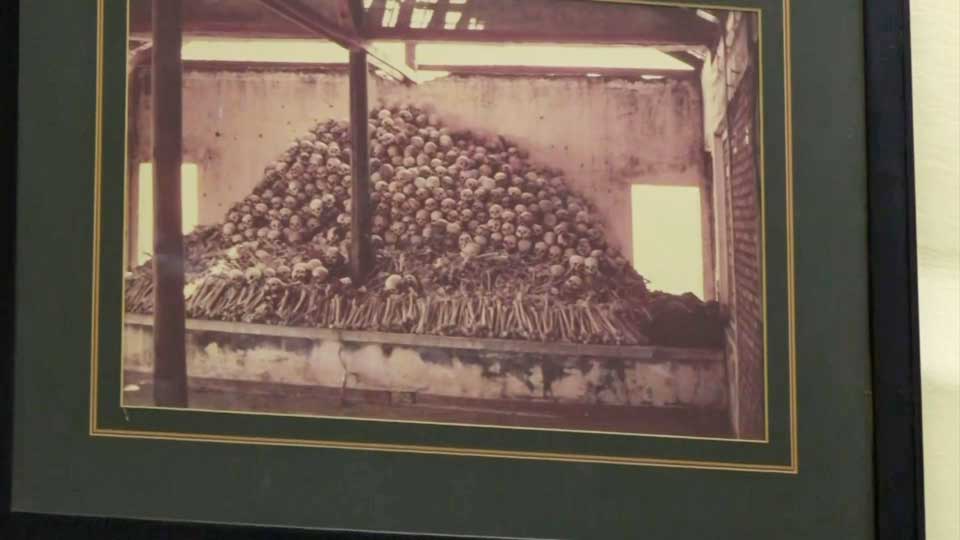

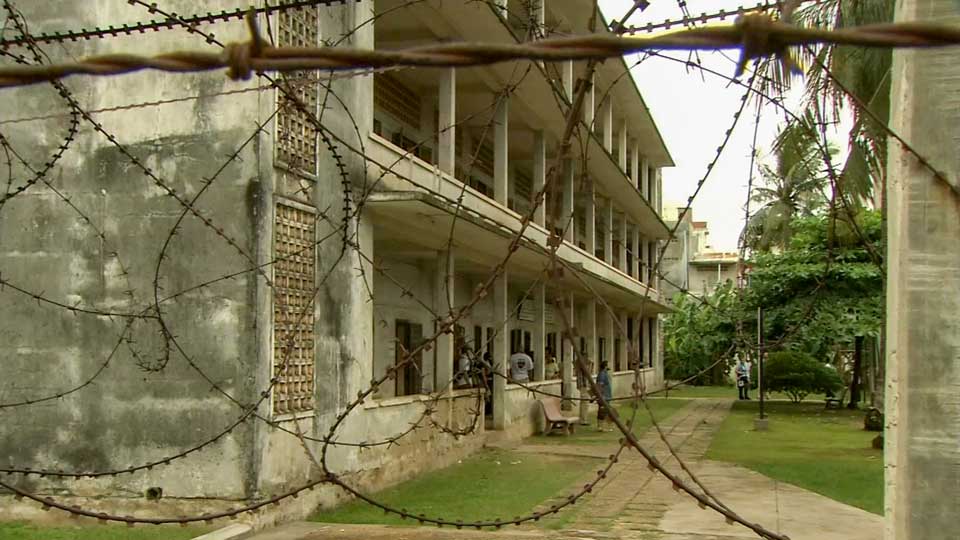

Norng Chan Phal, 53, is one of the few survivors of Cambodia’s notorious Tuol Sleng prison. He was just 9 years old when he and his family were locked up in the one-time school that served as a torture and execution center for those purged by the Khmer Rouge. More than 10,000 people died there.

"They started torturing my mother by kicking and punching her," he recalls. "She was kicked in the back and had her head slammed into a desk, which broke her teeth. Blood gushed from her mouth. I clung to my mother, but they beat her up again."

He and his mother were then placed in separate cells. One day he caught a glimpse of her from the courtyard. It was the last time he would ever see her. Both of his parents were executed.

A final trial

For more than 13 years, Norng Chan Phal has been watching as those responsible for the Khmer Rouge’s crimes stood trial. A special tribunal, established with the backing of the United Nations, prosecuted former members for the genocide that wiped out a fifth of the country’s population.

On September 22, scores of Cambodians gathered outside a courthouse in Phnom Penh as the final leader to be prosecuted heard the result of his appeal. Khieu Samphan, the 91-year-old former head of state, had been convicted of genocide and other crimes. The judge upheld his sentence -- life in prison. Cambodia does not have the death penalty.

Moving forward

The ruling drew a line of sorts under the darkest episode in Cambodian history. The country now enjoys a booming economy, and two-thirds of the population is under the age of 30, born long after the regime was driven from power. But those who lived through the period are increasingly asking: Is awareness of what the country endured waning?

Several organizations are keeping records of the horrors. NGO Prey Veng Documentation Center has been gathering testimonies from survivors, and organizing events where people share their memories with younger Cambodians.

Over the past 20 years, the group has interviewed more than 30,000 people. "They cry when they talk about their experiences," says director Pheng Pong-Rasy. "And they say they remember it all, as if it were yesterday."

Scars that never heal

In the village of Prey Tamau, about three hours’ drive from Phnom Penh, residents usually refuse to talk about the massacres. The pain is still too raw. But some agreed to share their stories.

Vorng Vin, now in his 60s, remembers witnessing executions and seeing people starve to death in his neighborhood. He says he still has harrowing nightmares and insomnia.

"A married couple was taken away for criticizing the regime," he recalls.

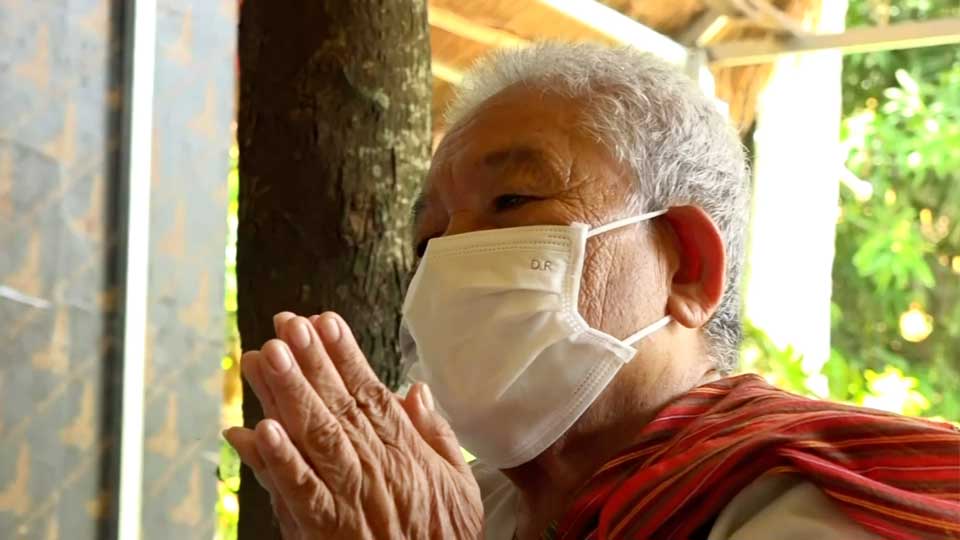

Torng Nhai, now in her 70s, says Khmer Rouge soldiers killed her husband and two brothers. She prays for them every day.

"I’m still devastated by the loss of my family," she says. "If the liberating forces had come just a little sooner, they could have survived."

Prey Veng Documentation Center has begun a program to share stories like these with school children. The aim is to ensure the next generation makes informed choices and can prevent a similar atrocity from happening again.

Decades on from the collapse of the brutal regime, and with the trials now in the past too, Cambodians like Norng Chan Phal and Pheng Pong-Rasy want their country to carve out a brighter future without forgetting the painful past.