Apollo 11 nearly didn't launch

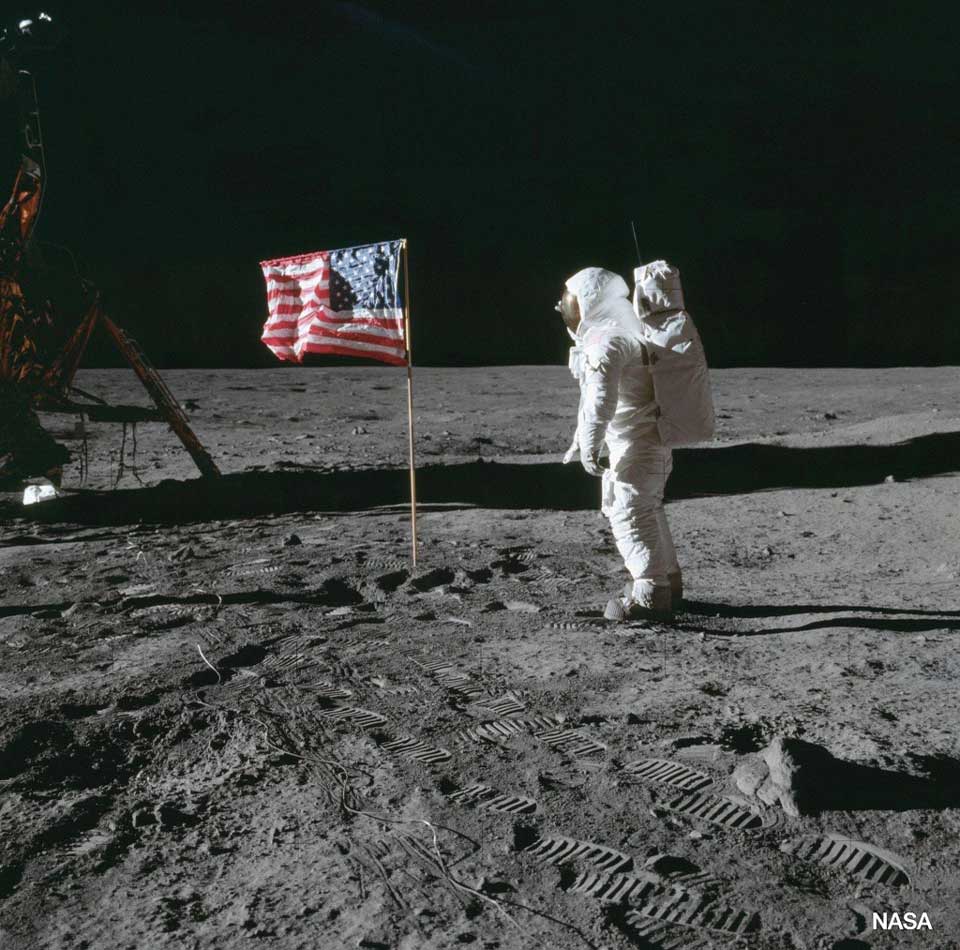

Apollo 11 was the most famous of the Apollo missions. On July 20, 1969, it landed the first humans on the Moon in a race to beat the Soviet Union and establish dominance during the Cold War.

Four days earlier, the Saturn V rocket sat atop Launch Pad 39A with approximately 1 million spectators along the beach anxiously waiting to see if anything would go wrong. At T minus 2 hours and 45 minutes, just before astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins arrived at the pad, the launch commentator announced, "We have a leak in a valve located in a system associated with replenishing liquid hydrogen for the third stage of the Saturn V launch vehicle."

A NASA Ask Magazine article on "Explosive Lessons in Hydrogen Safety" notes that, "Even small amounts of liquid hydrogen can be explosive when combined with air, and only a small amount of energy is required to ignite it."

While it may sound like an incredibly bad idea to let people anywhere near the massive Saturn V liquid hydrogen tanks, the Red Crews were standing by to fix the types of problems that require humans to physically approach the rocket while it's fueled. It's a dangerous job, and Red Crew technicians are accompanied by a safety lead who tries to ensure they don't blow themselves up.

The crew spent some time tightening the bolts around the faulty valve on the mobile launcher -- the tower connected to the rocket. After they left the pad, the team at the firing room console turned the hydrogen flow back on, but… the leak was still there. Without the full tank of liquid hydrogen, Apollo 11 wouldn't launch that day. Thinking fast, the Red Crew returned to the pad, filled their helmets with water from the emergency eyewash station, and tossed it onto the frigid valve to warm it up. This would stop the leak, but render the valve inoperable.

The leaky valve was supposed to be used to replenish the fully fueled hydrogen tank, and it ran automated from a giant IBM computer the size of a room. But there's more than one hydrogen valve. The engineers realized they could use the higher-flow main valve to replenish the fuel, but someone would have to very carefully control it manually from the console. Twenty-eight-year-old engineer Stephen Coester wrote the procedure change request, and engineer Jack Kramer, back from the Red Crew, operated the valve controls for the remaining 90 minutes until launch. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Artemis follows in Apollo's footsteps

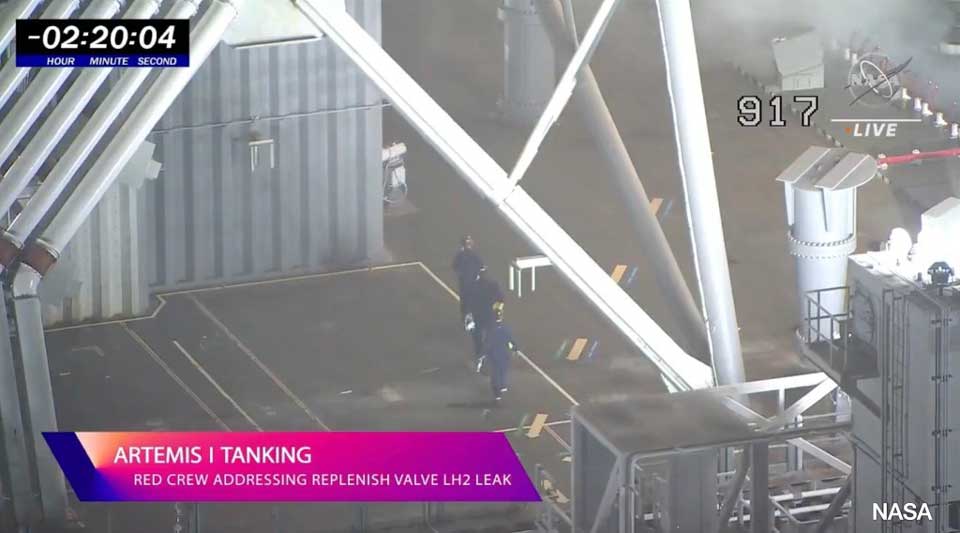

Last Tuesday night at T minus 3 hours and 17 minutes, Artemis I launch commentator Derrol Nail announced, "The launch team is tracking an intermittent leak on the core stage replenish valve. This is on the hydrogen side, location is at the base of the mobile launcher." Here we go again!

According to Mike Bolger, Exploration Ground Systems Program manager, the team discussed whether they should turn off the replenish valve and carefully flow hydrogen through the larger main valve, which had ultimately been the solution for Apollo 11. The cryogenics team did already have a procedure prepared to do that. But due to multiple hydrogen leaks on previous launch attempts and tests, the Artemis team was committed to a "kinder and gentler" approach. So they decided it would be better to tighten up the bolts on the replenish valve.

"There are times when you've just gotta put a wrench on a nut," Bolger explained.

The Red Crew, consisting of two technicians and a safety lead, drove out to Launch Pad 39B and climbed the stairs to reach the leaky valve. Red Crew member Trent Annis later recalled, "The rocket, you know, it's alive. It's creaking, it's making venting noises. It's pretty scary. On Zero Deck, my heart was pumping." They spent some time tightening the bolts, then left the pad. The firing room console turned the hydrogen flow back on, and… the leak was fixed! Phew.

The hydrogen leak, alongside some trouble with an ethernet switch at the US Space Force's radar tracking station, delayed the launch by about 43 minutes. But when the 98-meter-tall rocket finally lifted off into the night sky with an enormous roar and a trail of smoke illuminated by the fiery engines, it was truly a sight to behold.

Will Artemis continue to be an echo of the Apollo program, cut short by changing national priorities and a lack of public support? Or will it chart its own course to a sustainable, international human presence on the Moon and Mars? Time will tell. But for now, Artemis I is finally in space, due to the herculean efforts of thousands of people on the ground, including the three intrepid members of the Red Crew.