Government officials and central bank chiefs in many countries are moving to contain rising prices through aggressive monetary tightening. But that course of action could come at considerable cost. Some experts warn it may slow growth to the point where it triggers a global recession.

The International Monetary Fund has echoed this sentiment, warning that "increasing price pressures remain the most immediate threat to current and future prosperity by squeezing real incomes and undermining macroeconomic stability."

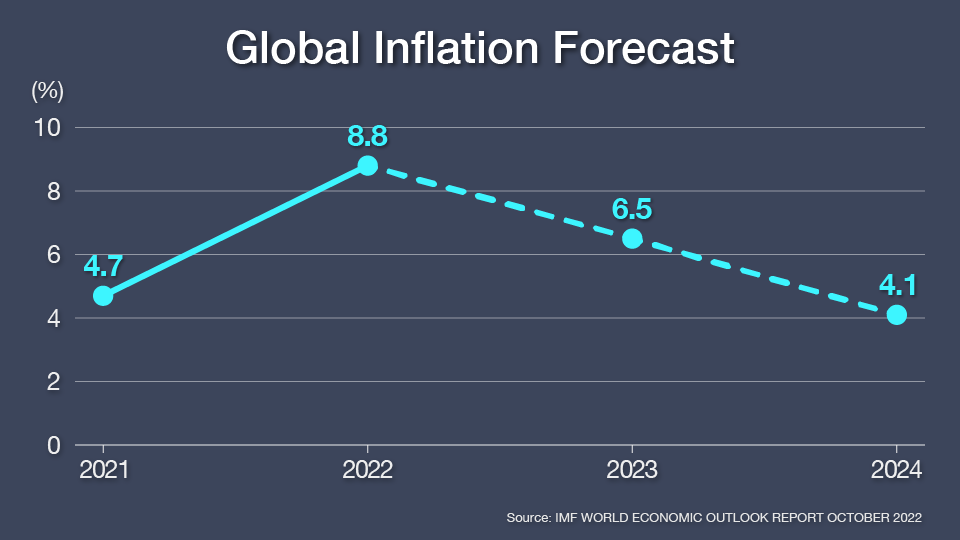

Some figures point to peaks

There are some signs of relief ahead. The IMF forecasts that the global consumer price index will top out at 8.8 percent in 2022, before declining to 6.5 percent in 2023. But the IMF also predicts that it may take more than a year before the index is back down to around 4 percent, where it was in 2021.

The inflationary spike is largely a result of the coronavirus pandemic and the Ukraine conflict, which have combined to drive energy, commodity and food prices to painful highs.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve Board has responded aggressively with a sustained course of monetary tightening. Policymakers are expected to go ahead with a fourth consecutive .75 basis point interest rate hike on November 2, a move that some fear will push the world to the brink of recession. Although the US unemployment rate is steady, the housing market is losing steam—so too, personal spending.

Side-effects felt everywhere

One of the most visible effects of the Fed's rate rises has been the rapid depreciation of currencies across the world. Countries in Asia have been hit especially hard. In Japan, the yen has lost about 20 percent of its value against the dollar since the start of the year.

The carnage on the currency markets has only deepened the global energy crisis. Brent crude oil prices fell nearly 6% between February, when Russia invaded Ukraine, and September. Despite that decline, almost 60 percent of oil-importing emerging and developing economies paid higher prices. That was because over the same period, their buying power plunged as their currencies tumbled.

Change of course in December?

With the specter of recession looming, economists and market watchers are watching the Fed for hints of what's to come. Some expect the central bank will slow its rate hike to .50 basis points as early as December. They point to recent US consumer price index data, which suggests the worst could be over. In June, prices were up 9.1 percent from the same month a year ago. But in September, the increase had tapered off to 8.2 percent.

Still, many others expect the hawkish policy in Washington will remain in place for the time being. They predict the US inflation rate won't ease to half its current level until summer 2023.

Kuroda goes his own way

The US is far from alone in trying to strike a delicate balance between containing using tightening to tackle inflation, and preventing a rapid slowdown.

At the other end of the policy spectrum is Japan, an outlier among the world's major economies.

The Bank of Japan has had a massive easing program in place for several years, and Governor Kuroda Haruhiko has suggested that won't change anytime soon. The yen has fallen to decades-old lows as a result.

Japanese authorities have intervened in the markets twice in recent weeks in a bid to halt the yen's slide, and their moves have paid off—to an extent. If the Fed slows its rate hikes, then that may have the added effect of slowing the yen's fall.

But any optimism must be tempered with a healthy dose of pragmatism. For the global economy, risk factors abound. Tensions between the US and China continue to simmer, and saber-rattling on the Korean Peninsula is another factor with the potential to trigger market woes. These and other considerations all have the potential to cause more chaos on exchange markets, and pain for Japanese consumers.