Business owners face tough decisions

At a small restaurant in Bangkok, staff have been serving up platefuls of khao moo tod (fried pork with rice) from just 25 baht, or 95 yen, for years. Recently the owner made the difficult decision to raise prices by 2 baht across the menu. It was the only way to keep the business afloat.

The manager says the depreciation of the baht hasn't just caused an inflationary spike in ingredients. It has also driven up prices for gas, plastic containers and transportation by around 10%. "There isn't a single product that is cheaper," says the manager. "Everything has become more expensive."

One female customer who has a low-income job says she understands the decision by businesses to hike prices, but that it has forced her to be more careful with her money.

Asian currency sell-off

In late September, the baht sank below 38 to the dollar -- its weakest level in 16 years. The slump has stemmed from the widening gap between the benchmark rates of Thailand and the United States. That disparity has driven currency traders to dump the baht and other Asian currencies for the dollar in anticipation of better rewards, a sell-off that is fueling a relentless strengthening of the dollar and pushing Asian currencies to historic lows.

The Indian rupee and the Philippines peso are both at their weakest ever levels against the dollar. So far this year, the Japanese yen has lost about 25% against the greenback, the Korean won about 20%, and the Malaysian ringgit around 15%.

Because the US currency is used to buy and sell goods globally, the immense strength of the dollar relative to Asian currencies has drastically increased the cost of essential imports such as gasoline and food products, and caused inflation to soar in many countries.

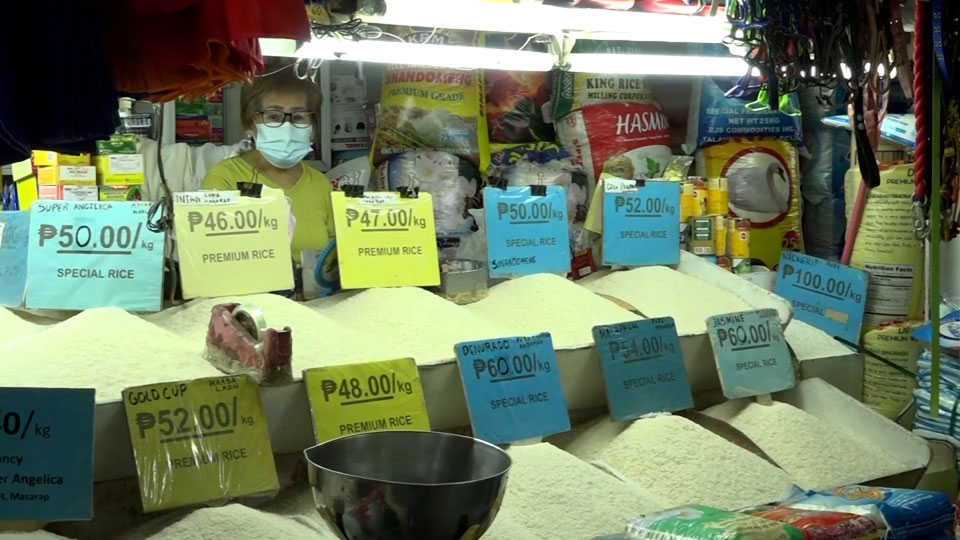

Rising price of rice

Rice hasn't been spared. The Philippines buys about 20 percent of its supply from neighboring countries, leaving it vulnerable to rising import costs. Recent data shows that prices jumped by 2.2 percent in August from the same month last year.

A 47-year-old mother of four says she can only afford to spend the peso equivalent of 68 US cents on a kilogram of rice. "I'm trying to save money by buying rice in smaller portions," she says. "If I buy in bulk, my family eats right through it. But now I'm worried that rice will cost too much when the dollar rises."

Soaring transportation costs

Commuters in the Philippines are also unhappy. The minimum fare for a jeepneys minibus ride has increased by 30 percent since June, the result of a government decision to raise public transportation costs to help drivers and operators cope with more expensive gas and diesel purchases. Gas prices are up by 30 percent since last year, while diesel has leapt by 70 percent.

"My mother tells me to save money because we aren't making enough," says one teenage school student. "The government should lower fuel prices because it's impacting students like me."

Memories of a past economic crisis

The situation has revived memories of the Asian financial crisis that gripped the region in 1997. In that case, the fuse was lit in Thailand, where the central bank ran out of the US dollars it was using to keep its currency stable. The baht collapsed from 25 to the dollar to around 50, stoking panic that rapidly infected other countries in the region.

At the time, Sawat Horrungrueang was the owner of two large Thai steel factories. He went bankrupt almost overnight and was saddled with an enormous debt. He has since paid the debt off and now runs a business with no exposure to currency fluctuations. "I'm much happier these days," he says. "The 1997 crisis killed my company. Now I don't have any business risk."

Sawat says the situation now can't be compared to the 1997 crisis because there are too many other factors at play, including the conflict in Ukraine and the coronavirus pandemic. But he adds an ominous warning: If a major crash is coming, it will happen at a time we don't expect and with an impact we can't foresee.