Amigos is a support group that provides medical assistance to uninsured foreigners in the greater Tokyo area. Executive director Nagasawa Masataka is in regular contact with Mehmet and his family, whose refugee applications have been rejected. That means they have lost their status of residence and thus have no medical insurance and must pay out of pocket for any expenses.

Support groups step up

The coronavirus pandemic has forced many foreigners without residential status to lean on groups like Amigos. Between 2018 and 2021, the organization's annual expenses rose more than 12-fold. It spent almost $200,000 last year, about half of which was for their medical treatment.

"There are lots of people who are struggling without money and are excluded from the healthcare system," says Nagasawa. Many are dealing with serious illnesses, including cancer and diabetes.

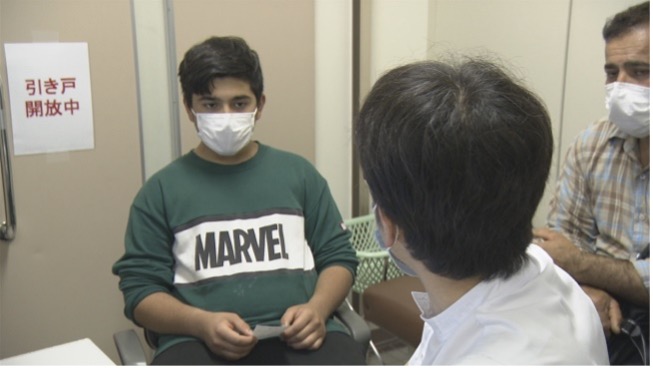

Mehmet has been diagnosed with arrhythmia, an abnormal heart rhythm that can cause cardiac arrest. At the Saitama Cooperative Hospital, Doctor Inaba Osamu says the teen needs surgery.

The cost of surgery

However, Mehmet's father Bayram is unable to pay for the operation. He was told he would have to provide $22,000 dollars in advance. Ever since, Bayram has been in discussions with five hospitals without success. If he was part of Japan's national health insurance, the out-of-pocket expense would only be $400-$800.

In the meantime, Mehmet takes prescription medication to treat seizures. It costs $25 dollars for 10 pills, which is paid by Amigos.

Nagasawa says many hospitals in Japan set higher medical fees for foreigners, in some cases, up to 300% the usual amount, to protect hospitals from ballooning costs in the event of an unforeseen medical situation.

This means uninsured foreigners are often sent away unseen. "Visiting a doctor for a simple cold incurs an out-of-pocket expense of $25 for people with medical insurance," says Nagasawa. "But an uninsured foreigner without income has to pay up to $250 dollars for the same consultation."

Forced to flee Turkey

Bayram, his wife Yuksel and their four children are asylum seekers. The family arrived in Japan five years ago. He says they were forced to flee Turkey: "I was persecuted. My parents were persecuted. I thought things would improve if I had children. But when they started going to school, they'd get: 'You're Kurds. You're terrorists. Don't sit next to me.' We were scared. We had to escape."

Bayram initially received a six-month temporary visa that he kept renewing while applying for refugee status. He found work at construction sites.

Last year, the family welcomed a new member, baby Hasan. Mehmet is now in his third year at the local junior high school and is fluent in Japanese. But he has to hold back during physical education classes because of his heart condition.

Bayram's refugee application has been rejected three times and he and his family have lost their temporary visa. They have been ordered to return to Turkey, but they cannot.

Life in limbo

Losing residency status destroys the basis of living, says Bayram: "You lose your chance to work, you lose access to hospitals, doctors, and banking. I sit at home, my hands and arms tied. I cannot take care of my family. Even my children are scared of going outside."

The situation has put more pressure on Mehmet: "I'm taking care so my heart doesn't start to hurt," he says, adding that he tries to avoid going to hospital because he does not want to be a burden.

There is no official system for addressing the medical needs of the estimated 75,000 or more foreigners without status of residence living in Japan. Immigration authorities say they are ineligible for public welfare, because they are supposed to leave the country.

The Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare has also stepped away from the problem, leaving it to the discretion of hospitals. That leaves people like Mehmet and his family in limbo.

Low-cost medical service

In April, Nagasawa introduced Bayram to the Saitama Cooperative Hospital, one of two hospitals in the prefecture that offers free or low-cost medical services. The scheme was created by the government for Japanese people who temporarily lose access to health benefits, but it has become incidentally valuable to foreigners. If the hospital finds Mehmet eligible, it would cover part of his medical costs.

The hospital is in Kawaguchi, a city with a large foreign community including an estimated 2,000 Turkish Kurds. Many are uninsured. It offers low-cost medical services, but receives no subsidies from the government and bears the entire cost. So, the decision to accept uninsured foreign patients has been expensive. In 2020 alone, the hospital was saddled with unpaid medical bills for 81 patients totaling $82,000. "It's impossible for us to exempt a patient from all of their medical expenses," explains Takemoto Kozo, a case worker assigned to Mehmet. He says there should be a public system that ensures medical care for every person who needs it.

Eventually, the hospital accepted Mehmet into its low-cost program for daily medical services, but it is unable to perform the type of surgery he needs – another major setback.

Losing hope

Mehmet's family faces another uncertainty. The prospect of either parent being detained by immigration authorities at any time because they are refusing to leave the country. Their Japan born baby, Hasan, was the only one to have kept his visa, but it was canceled that day, and he too lost his status of residence. "I kept begging," says Bayram. "But they said we're just supposed to go back to our own country. I tried to show them our hospital documents, but they said they didn't want to see them."

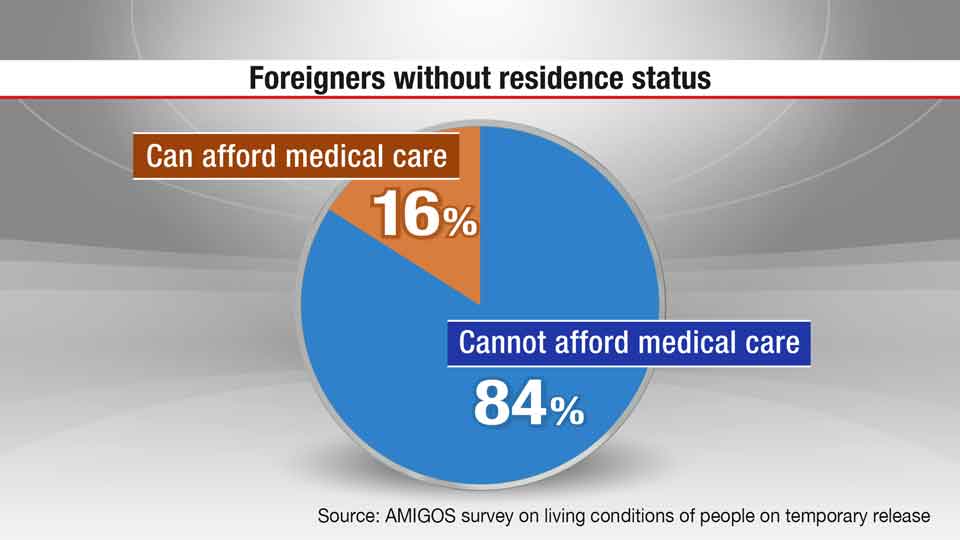

Nagasawa is working to raise awareness of the issue. Earlier this year his organization held a press conference to publicize a survey of 450 uninsured foreigners. An overwhelming majority, 90 percent, described their living conditions as "very difficult" or "painful."

A similar figure reported that financial problems prevented them from visiting a medical institution, and 79 percent said they had an existing illness or injury they could not afford to treat.

To address the situation, Amigos organized a free medical advice session for foreigners in need in Ota, Gunma Prefecture this June. During the session, an emergency occurred: A Nigerian woman with a heart condition suddenly fell unconscious, but doctors struggled to find a hospital for her. Around her that day were about seventy people waiting to be examined. None had medical insurance.

Community support

Despite their rejection by the Japanese government, Mehmet and his family have been warmly welcomed by their local community. Almost every night, Mehmet takes food cooked by his mother to their landlord's house across the street. Ando Kenichi, 79, lets the family stay rent-free.

Ando used to employ Bayram in his building maintenance business. Ando says when back injuries hindered his own ability to work, Bayram saved his small company. The pair became friends.

Ando says it is hard to find Japanese people willing to do manual labor. Many small firms can hire only foreigners. When Bayram lost his visa, Ando was forced to put his business on hold.

"I am in great trouble and the situation is really depressing for an old man like me. If we do not look more toward good people that work more than the Japanese, I think it will be us Japanese who at the end will suffer the consequences. I don't think those white-collar university graduates at Immigration or Ministry of Justice realize how much we need each other," says Ando.

He wants to offer to become Bayram's guarantor with immigration authorities and is considering gathering signatures in the neighborhood for a petition in support of the family.

An anonymous benefactor

At the Saitama Cooperative Hospital, case worker Takemoto and other staff are trying to make a change after their dealings with cases like Mehmet. Discussions are underway with Kurdish community support groups to try to offer better care.

Takemoto feels that hospital staff's lack of knowledge and awareness results in many uninsured foreigners being sent away when solutions could have been found. He is working on a survey of medical professionals to understand the issues.

For Mehmet, there looks to be a happy ending, at least when it comes to his heart condition. An unexpected and unidentified benefactor has come to the rescue. In June, Nagasawa 's organization received an envelope with more than $3,700 inside. An anonymous note stated the money is to be used for Mehmet's operation.

"Just like that, and in this ordinary envelope!" says Nagasawa. He immediately reached out to Takemoto, who in return, informed him that he had found a hospital to perform the surgery.

"I am so glad to hear that my heart will not hurt again," says Mehmet. He is now looking forward to a more active life. "I can do any sport I want."

Bayram is overwhelmed. He knows his son is fortunate. But at the same time, he worries that the underlying problem remains.

"Foreigners need a visa and insurance," he says. "These are basic rights to be able to live. Everyone needs them. To not recognize the basic rights of refugees is to abandon them to suffer and even die."

Nagasawa says people seeking refugee status don't get a safety net until they get residential status, and those who lose that safety net are at the very bottom of society.

"We can't overlook this. We can't simply say they should go home when most just can't. We have a responsibility to look after them, as we live together." he says.