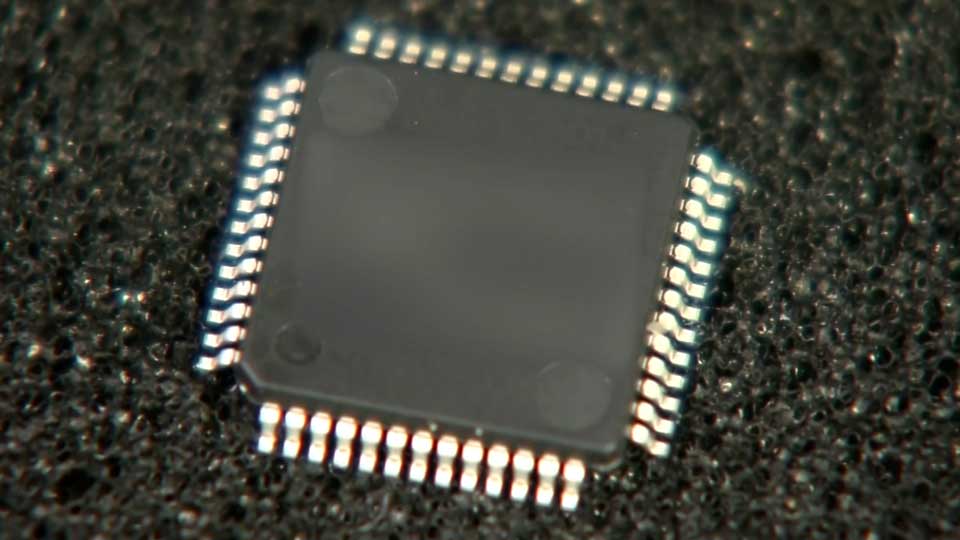

Semiconductors are an essential component in all manner of appliances and devices, from computers and smartphones to medical equipment. They also have many uses in automobiles.

Since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, production has shrunk dramatically, even as demand skyrockets. Japan Research Institute senior economist Nogimori Minoru says the shift to remote working is a key factor.

"The pandemic has seen huge investment in data centers and devices for remote working. As a result, we've seen global demand grow steeply and exceed supply. Home electronics and automobiles are hit especially hard."

China's zero-COVID policy poses risks

Shanghai is a major semiconductor export hub. The Chinese city's lockdown this year cut shipping volumes, but supply chains are edging towards recovery since restrictions were lifted in June.

Still, Nogimori doesn't think supply can fully bounce back. He warns China's coronavirus policy could mean another lockdown at any moment.

"In China, the overall zero COVID strategy is still in place. There is a risk that very strict activity restrictions could continue adversely affecting the semiconductor industry."

Major economies seek solutions

Some nations – and companies – are making their own plans to shore up supply. The United States is looking outside China to work with friendlier governments including South Korea and Taiwan.

"The US and China are increasingly at odds," notes Nogimori. By building closer relations with other Asian nations that produce semiconductors, Washington is seeking to reduce economic security risk.

"'Friend-shoring' is a way of separating global supply chains from external economic coercion. There is great potential in India and Southeast Asian countries," Nogimori explains.

Japan was once a major semiconductor producer, but shifted away from the industry in the 1980s. It is now looking to jump back in with a government-supported partnership with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company.

"Japan can foster a cutting-edge semiconductor industry in the future. Manufacturing equipment and silicon wafers are areas in which Japan has an advantage. There's strong market potential," says Nogimori.

The project will see the construction of a chip plant in southern Japan, with production expected to start in 2024. Output is expected to focus on high-tech industries like artificial intelligence and robotics.

Dark clouds over neon supplies

Nogimori warns the ongoing conflict in Ukraine could cause delays. Ukraine is one of the world's leading exporters of neon, another important material for chip manufacturing. Russia's invasion has left global supplies dangerously short.

"Neon is difficult to substitute in production," says Nogimori. "Major chip firms have decent amounts of stocks for now, but they will bottom out within several months. If the war in Ukraine continues, we will see global chip shortages in the near future. Some firms, including in Japan, have started producing neon. But again, they'll need time to build up."

Nogimori predicts that even if supply chains do recover, the world is at least one year away from meeting the pace of semiconductor demand.