Rising costs

Japan is finally seeing prices rise after over three decades of almost no inflation. Though the increases are not as steep as they are in the United States and many European nations, consumers and businesses are feeling the impact.

"I hate price increases as I'm living on a pension," one shopper told NHK.

A company manager called the business environment "far from ideal."

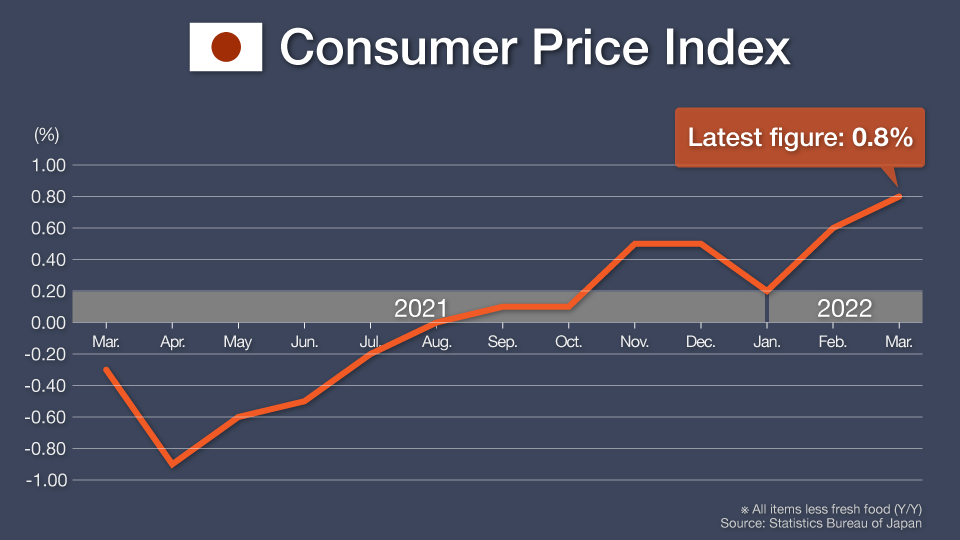

These observations are borne out in the data. Japan's latest consumer price index excluding fresh food, called core CPI, came in at 0.8%.

Experts say the rising prices are mostly due to external factors. Momma Kazuo, executive economist at Mizuho Research & Technologies and a former Bank of Japan executive director, says, "The inflation in Japan is due to price increases overseas." Prices of commodities ranging from oil to flour are rising around the world because of robust post-pandemic demand in the US and Europe, as well as supply constraints exacerbated by the Russia-Ukraine crisis.

Yamamoto Kenzo, another former Bank of Japan executive director and representative of Office KY Initiative, adds, "The inflation in Japan now is due to higher import costs, not domestic factors. A weaker yen is only compounding the issue."

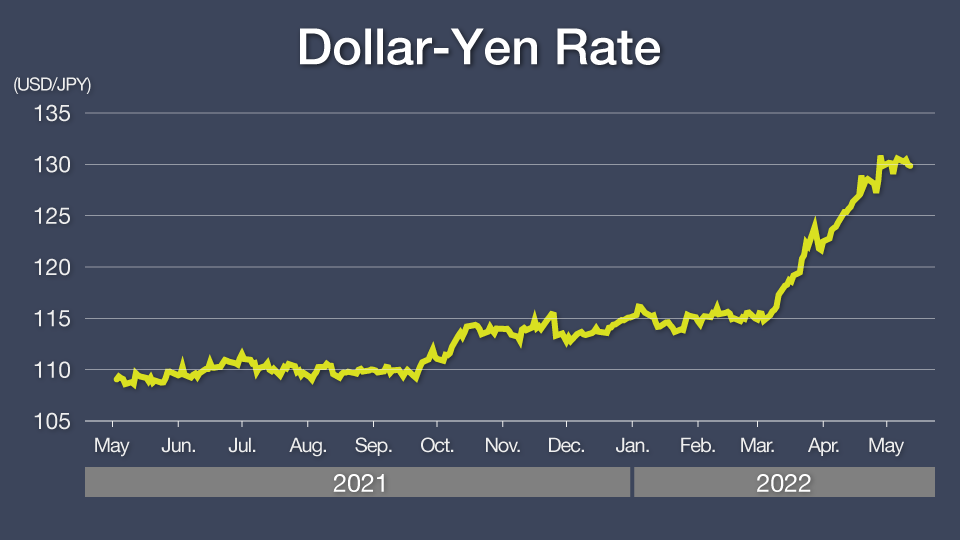

Weaker yen contributes to price increases

The yen has plunged against many currencies in recent months, hitting a two-decade low against the dollar. This is the result of the BOJ's decision to stick with its ultra-easy monetary stance even as its peers, such as the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, tighten their measures. The crux of the BOJ policy is to keep long-term interest rates near zero by purchasing bonds. As rates rise in other countries, investors are dumping the yen in favor of other currencies. This is because assets in countries with higher yields tend to look more attractive to investors.

Like Yamamoto, Momma believes the weaker yen is fueling inflation. "Three-fourths of inflation in Japan is due to surging commodity prices overseas, while one-fourth is due to the weaker yen," he says, adding that this calculation is based on comparing the yen-based import price index with the dollar-based one.

2% inflation target in sight

With higher import costs and a weaker yen pushing up inflation, experts predict the core CPI for April onward will likely hit 2%.

Yamamoto says, "I see a high possibility of core CPI hitting 2% as early as April, with the index going over the threshold in the months after."

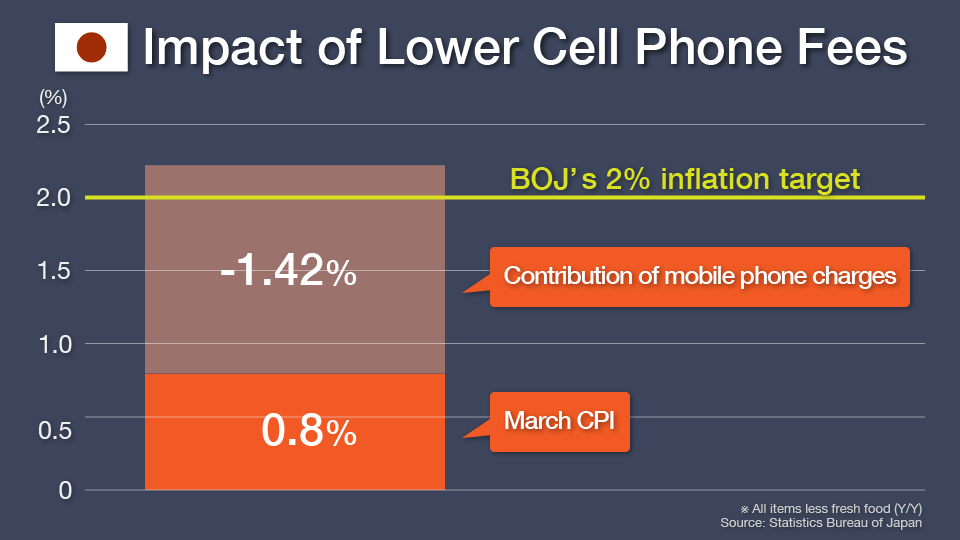

Momma has a similar outlook. "The core CPI should surge in April to around 2%. This is because the effect of lower cell phone fees will dissipate from April onward."

Momma is referring to the effects of Japan's major telecom firms slashing mobile phone fees starting in the spring of 2021 in line with a request from then-Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide. Lower cell phone fees dragged down the March core CPI of 0.8% by 1.42%. If the effect of the lower fees was not taken into account, the March figure would have come in at 2.22%. As the CPI is calculated on a year-on-year basis, figures from April 2022 will not be dragged down by the lower cell phone fees.

This may be significant because the BOJ uses the core CPI to decide policy, and 2% is its inflation target. From April onward, Japan has a high likelihood of reaching the central bank's inflation target.

BOJ policy explained

If inflation hits the BOJ's 2% goal, does it mean the central bank will stop its easing? Apparently not.

BOJ maintains easing

The Bank of Japan, at its April 27-28 monetary policy meeting, maintained its ultra-easy stance. This means keeping short-term interest rates at minus 0.1%, and long-term yields at around 0%. The central bank also signaled that the loose policy is here to stay.

Momma and Yamamoto say the 2% target has no significance on BOJ policy now because inflation is due mostly to external factors. Therefore, achieving the goal would not necessarily mean the Japanese economy is in the state the BOJ desires.

Momma explains, "The price gains in Japan are mostly due to the rise in global commodity prices. For Japan, this just means higher costs; it's not as if the rise in inflation is due to a strong domestic economy."

Yamamoto adds, "Ideally, prices would go up after demand strengthens and wages increase. However, the current rise in prices is due to higher import costs, not wage increases stimulating demand."

Mixed thoughts on easing

Given that nine years of unprecedented easing has not helped the Japanese economy get to where the BOJ wants it to be, how do experts evaluate the central bank's policy?

Yamamoto thinks the ultra-easy policy has been implemented for too long. "Quantitative easing is a shock method of sorts," he says. "It's the same as a powerful drug: it works well in the initial stages, but the effects wear off and it leads to side-effects if used long-term."

Yamamoto cites three side-effects as special causes for concern:

1) The distortion of market mechanisms due to the BOJ keeping long-term interest rates near zero:

"When interest rates are decided by the markets, companies that are not productive or profitable have no choice but to go out of business because they can't borrow money. Meanwhile, growing firms will thrive in a free-rate environment." Yamamoto believes the BOJ's ultra-easy policy has prevented the market from naturally eliminating weak firms and shoring up the strong ones.

2) A lack of fiscal discipline:

"The government keeps issuing bonds on the premise that they will be bought up by the Bank of Japan. That has led to government officials not thinking about revenue when deciding expenditures."

3) The damage to the profitability of Japanese financial institutions:

Lower interest rates mean lower profit margins for banks because they normally benefit from the difference in the long-term rates they receive and the short-term rates they pay to people and companies. "Financial institutions have the important role of an intermediary in the economy, so if their profitability wanes too much, it encompasses the risk of the financial system itself weakening."

Thus, Yamamoto believes the Bank of Japan should gradually stop trying to push down long-term interest rates.

Momma agrees that the central bank should relax its grip on long-term interest rates, but believes now is not the time to do so. "Demand in Japan is still weak, and real GDP is 3% lower than before the pandemic," he says. "If rates went up, it would cool domestic demand even more."

Momma says, "The Bank of Japan has no choice but to continue its ultra-easy policy while watching out for the side-effects." However, he thinks the right time to reduce easing will come in the next two to three years, because the economy has the power to self-improve as individuals and companies work hard to better their situations.

Although Momma thinks the unprecedented monetary easing should be pulled back when the economy is ready, he does say it can be considered a success. The Bank of Japan has been criticized for not making the economy strong enough for inflation to hit 2% due to domestic factors, but Momma notes, "BOJ policy did pull Japan out of deflation and stabilize prices within one year of quantitative easing. As it continued, Japan saw the job market recover and experienced the second-longest period of postwar economic expansion. It can be said that even though 2% inflation wasn't achieved, Japan's economy did become stronger due to the BOJ's easing."

Furthermore, Momma believes the easing over nine years was important in proving something. "The Bank of Japan has, by loosening policy as much as it could, dismissed the notion that inflation was lagging because there wasn't enough monetary easing."

Momma adds that for prices to rise due to domestic factors, structural reforms are needed instead, but he doesn't think inflation needs to reach 2%.

BOJ need not target 2% inflation

Momma stated that the BOJ should shift its focus away from 2% inflation and instead strive for price stability. "There's actually no harm to the economy if it's neither in inflation nor deflation," he says.

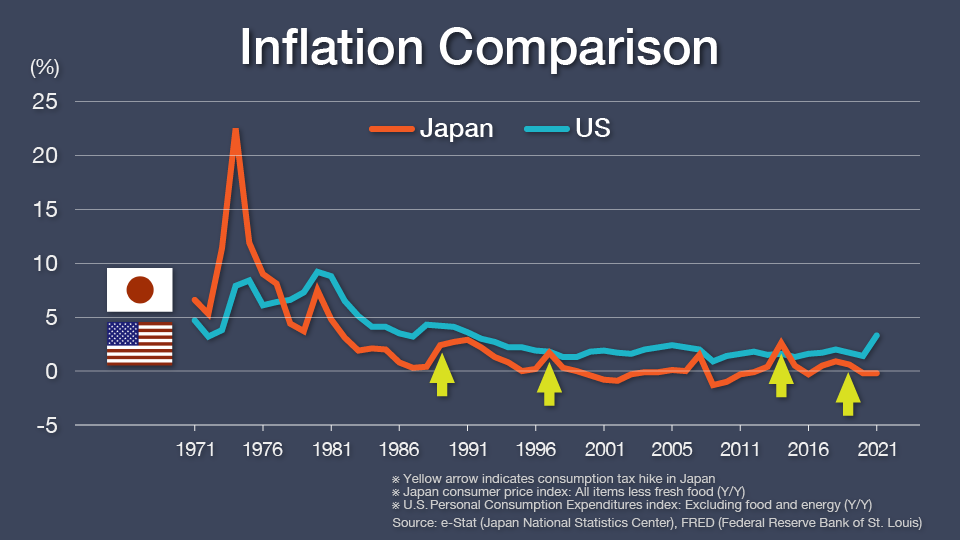

Yamamoto agrees, adding the 2% target is largely out of the BOJ's grasp anyway: "Since 1978, prices in Japan have always been lower than those in the US except when Japan hiked taxes. Prices in the two nations have correlated, with Japan's inflation lower by about 2% on average. This means that the only time Japan's inflation can hit 2% is when the US fails to control prices around its 2% target, like now."

Yamamoto also argues that 2% is an unsuitable level of inflation for Japan anyway. "The strength of the economy, its structure and the state of the jobs market differs from country to country, so the right level of inflation depends on that. For Japan, 2% is too high."

Dissecting Japan's problems

Yamamoto explains that social norms play a role in Japan's economic situation. "Since experiencing stagflation in the 1970s, the Japanese have an implicit understanding that job stability and corporate stability are important," he says. "The public sector, the private sector and individuals all act according to this understanding. Bankruptcy and layoffs are avoided at all costs, so it leads to many inefficiencies within the economy. As a result, Japan is no longer a market-oriented economy with competition." Yamamoto says the social approach needs to change for the economy to grow.

Momma adds that it is difficult for a country to advance economically as it deals with an aging population: "The number of people who can work and be productive are on the decline. There's not much that can be done. However, Japan isn't lagging when it comes to productivity growth per person. In that respect, it's performing quite well economically."

Calls for the government to step up

As for addressing the situation at hand, Momma says there is nothing Japan can do regarding current price rises as they are due to external factors. "Japan can't control oil output overseas or suddenly produce large amounts of wheat," he explains. "However, there are ways to help those struggling from the high costs. Important to note, though, is that those ways are only available to the government. Central banks control interest rates, which can stimulate the whole economy, but that means they cannot target a certain group of people to help. I believe it's the government's job to come up with measures to support those impacted by higher prices and a weaker yen."

Momma adds that central banks can only address inflation when demand is strong. "When price gains are demand-led, as they are in the US now, rate hikes can cool sentiment."

Keeping watch on BOJ policy

The Bank of Japan has gone further with its easing policy than any other central bank at any time in history. Whether it should wind down easing -- and when -- is a matter of debate. Analysts around the world are watching the central bank closely, especially with BOJ Governor Kuroda Haruhiko's term coming to an end in the year ahead.