The DRC is the world's largest producer of tantalum, a mineral used to make smartphone and computer capacitors. Armed groups dominate in the mountainous eastern region where the material is mined. A battle for control has raged on for two decades, taking the lives of more than five million people. The conflict is the deadliest since World War Two.

The United Nations refugee agency says as of November last year, 5.6 million people had been internally displaced. The number of those forced to flee the country exceeds 800,000.

Fittingly, the DRC's tantalum is known globally as a "conflict mineral."

Trade comes at 'great human cost'

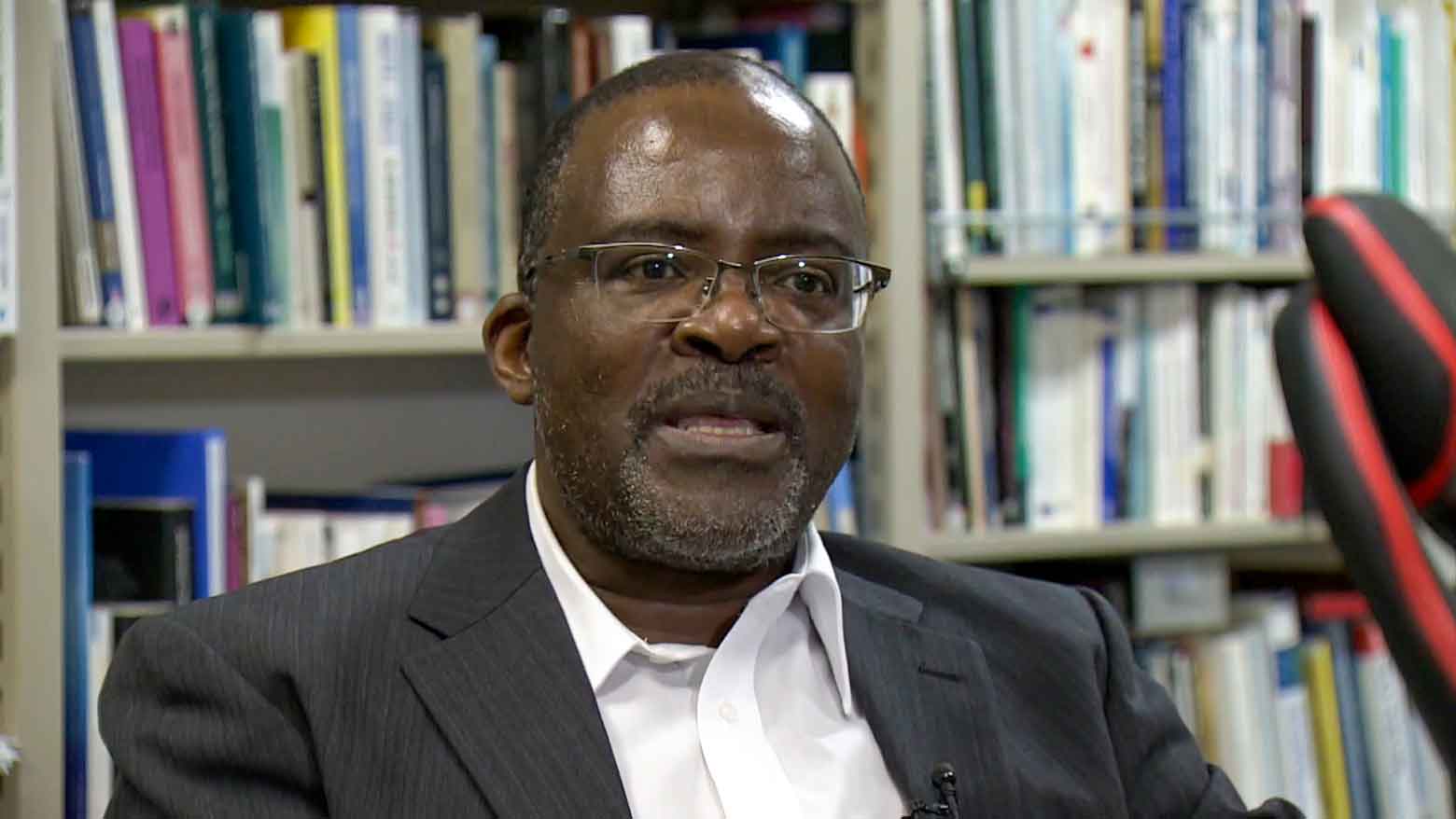

"People in the eastern DRC feel like nobody cares about them, that nobody knows about their suffering," says Jean Claude Maswana, a professor of economics at Ritsumeikan University in Shiga Prefecture.

Maswana grew up in the DRC's capital Kinshasa, and has lived in Japan for more than 20 years. People in the war-torn provinces regularly update him about the conflict.

During a recent conversation with a civilian group leader in South Kivu province, Maswana learned that residents in several villages were forced to leave their homes due to fighting. Some were killed as they fled.

"The exploitation of the minerals comes at a terrible human cost," he says.

Efforts to stop abuses fall short

Some countries have been trying to prevent DRC-sourced tantalum from entering the global supply chain. The US government has required companies to disclose whether their products contain minerals from the African nation since 2010. And the European Union enforces a similar measure.

But tantalum and other conflict minerals such as tin, tungsten and gold are often traded across multiple continents, making it difficult to trace their origins. One survey found that only 6 percent of firms in Japan are able to identify where their materials originally come from.

And even when the routes are known, Maswana says there are no mechanisms in place to hold abusers accountable. He points out that most companies are quite happy, as long as the going is good. "The world has turned a blind eye to what's going on at the source to keep business going," he says.

Hanai Kazuyo, an assistant professor at the University of Tokyo who specializes in conflict minerals, is calling for much stricter regulations. She argues that those in place right now have a limited effect due to smuggling, lack of oversight, and corruption.

"The international community should focus more on monitoring efforts upstream, and also allocate more human and financial resources for that purpose," she says. "Also, companies in the electronics industry should support those efforts."

Refugees give new life to computers

In Japan, some business are taking heed. They include People Port, a startup in Yokohama that wants to end the reliance on conflict minerals. It was founded in 2018, and specializes in the sale of secondhand computers. Four asylum seekers from Africa are among the firm's 12 staff members. They all fled from violence and persecution.

"Just to make one PC, so many bad things happen," says one African staff member who wished to remain anonymous. "Because of war, children are losing their parents. I've seen the bad effects."

Most of People Port's computers contain capacitors made with tantalum. CEO Aoyama Akihiro truly believes refurbishing and repairing old models can help reduce the world's reliance on conflict minerals.

People Port sells them online, and also at pop-up stores around Tokyo. The company has traded more than 3,000 units in the past two years. Aoyama says the prices — refurbished models typically cost half the price of new models — mean demand will continue to grow. He also believes consumers are becoming more conscious.

"I want people to think more about what's behind the products and services they use, and the situations they are connected to," he says. "I hope the story about our PCs becomes a good opportunity to think twice when making choices."

EVs increase demand for cobalt

The global shift toward carbon neutrality is pushing up demand for cobalt, an essential material in the lithium-ion batteries that power electric vehicles. The DRC accounts for about 70 percent of the world's supply, and estimates point to a six-fold rise in demand by 2040.

The country's small, unregulated cobalt mines are notorious for human rights abuses, including the use of child labor.

Another Japanese company is developing ways to source the material more ethically. JX Metals Circular Solutions, located in Fukui Prefecture, has pioneered a method for separating high-purity cobalt from old lithium-ion batteries. The plan is to use the recycled mineral in new EV batteries.

Breaking the cycle of violence

Maswana and Hanai know that efforts like this do make a difference, but they really are only the tip of the iceberg when it come to the degree of human suffering. They hope to see more innovative solutions in the coming years — and crucially, a much bigger push to stop the violence.

"One of the big reasons these sorts of crimes have gone on for so long is impunity in the DRC," says Maswana, meaning that if abusers get away without being punished or penalized, there's no incentive for them to stop. "There needs to be a justice mechanism to start breaking the cycle. Otherwise, warlords will always find a way to channel these conflict minerals into the global supply chain."

The team at People Port feel the same. As a small operation, they take pride in the steps they have taken so far. "The amount we can refurbish may be limited," says Aoyama, "but the story about our products can carry a bigger message to help change the consumer mindset."