Only about half of the country's teachers and students reportedly returned to school this year, where the junta-run curriculum is said to discourage free thought.

The rest are working outside the system.

Elementary school teacher Shar Myar is among 230,000 teachers who are on strike.

It is a risk to take part in the CDM and she has been following reports of an increasing number of her colleagues getting detained.

Fearing for her safety -- and that of her family -- Shar Myar fled Yangon. The 23-year-old is now at a camp for displaced people in Kayah, along with more than 3,000 others.

Children aged 12 or under account for about a quarter of the camp's population. For a long time, they have not been able to go to school.

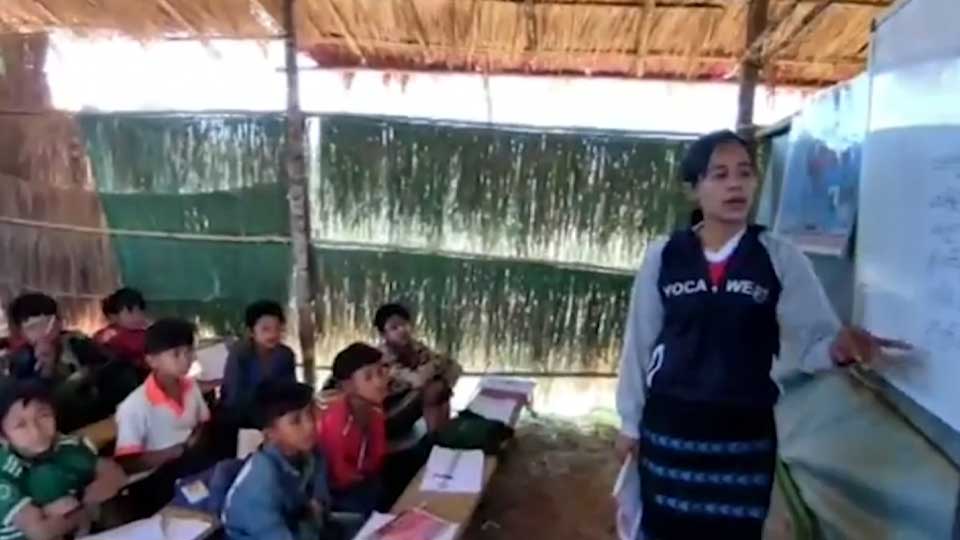

Shar Myar decided to continue her teaching at the camp, joining others who are running classes.

"I noticed that these children have been away from school for so long," she says. Now that schools are open, "at least they will have friends, which helps their overall education and mental well-being."

Shar Myar says camp life is hard. Food and clean water are scarce, and classrooms have been erected amid wind and dust in the mountainous terrain.

"When military planes fly overhead at night, we worry about whether they will bomb and kill us. Some children hide as soon as they hear an airplane sound. They're living in a constant state of fear," she says.

Shifting online

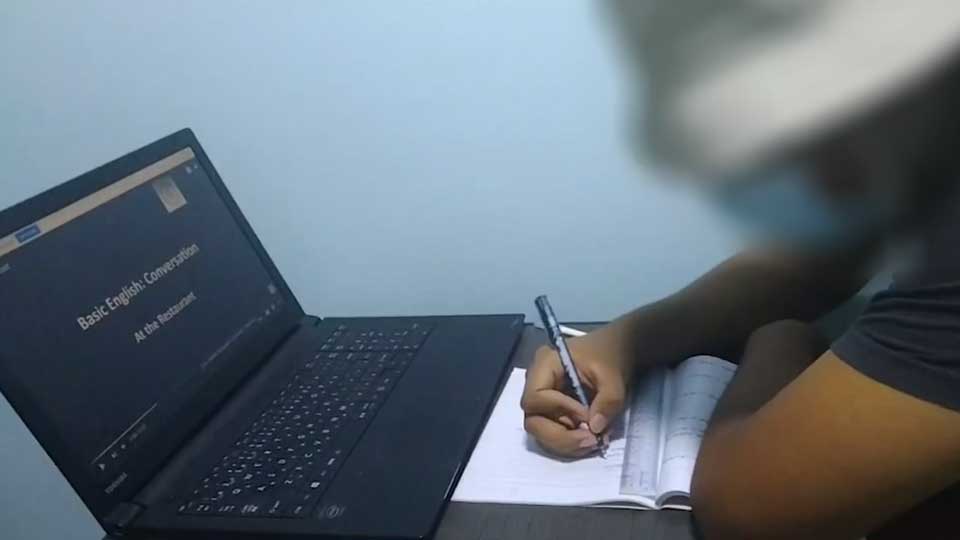

In Yangon, high schooler Yan Aung, not real name, has been taking an online class since November in a program run by democracy activists.

The 17-year-old wants to follow a military-free curriculum that is consistent with democratic principles.

"Under the previous government, our education slightly improved, but now, it's gotten worse," he says.

Yan Aung's preference for online learning is influenced by his fear of the military. Walking to school poses a risk of being kidnapped and taken hostage.

"Every student that is part of the CDM is at high risk of being detained. We may be arrested if they come to our houses and ask our age, and question why we're not in school," he says. "Because my house is near the school, I shut all the doors and windows when soldiers are passing by."

Aside from those day-to-day concerns, Yan Aung worries about what lies ahead.

"If the coup goes on, there's no way in knowing when I'll be able to attend university," he laments.