The support measures have been put in place after health officials could not find a hospital bed last August for a woman who was infected with the coronavirus while eight months pregnant. She was forced to give birth at her home in Chiba Prefecture, near Tokyo, and the baby died.

At the time, Japan was facing a surge of Delta-variant infections. The then Chief Cabinet Secretary Kato Katsunobu asked local governments to ensure infected pregnant mothers get better care.

Pregnant women at the front of the line

Ensuring that pregnant women get priority for vaccinations was one of the first changes. That measure was implemented in late August after several studies, including one published by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, offered assurances that the shots are safe for mothers-to-be and fetuses.

Medical evidence also emerged that women who contract COVID-19 during pregnancy are at increased risk of preterm birth.

Officials in Okayama Prefecture, western Japan, were among the first to act.

"Vaccination is vital to protect pregnant people from coronavirus, as they are at an increased risk for severe illness from COVID-19," said Governor Ibaragi Ryuta. "We are now confident to encourage every pregnant woman to get vaccinated, no matter what stage of their pregnancy."

A full-term woman at a vaccination center in Okayama told NHK that she felt less anxious after receiving a shot. "I was quite worried when I saw the news about the baby’s death in August," she said. "I was also worried about an adverse reaction to the vaccination, but I decided to go ahead with it."

The prefectural government is now preparing to offer boosters. They are available in Japan for those who received their second vaccination shot at least six months ago. Most pregnant women in Okayama are yet to pass that required period, but officials say they will encourage them when the time comes.

Monitoring infected mothers

Vaccination does not offer complete protection against the virus, however, so some pregnant women are still getting infected.

Chiba Prefecture has new equipment to track the health of pregnant women and ensure they can access a medical facility in case of emergency.

By the end of January, more than 30 expectant mothers had been issued with devices that monitor fetal heart rate and contractions of the uterus. The data is automatically linked to medical facilities, where staff can react quickly to any problems.

Prefectural officials have also set up a network that shares information. Instead of having to contact a medical facility one by one to find a hospital bed for a pregnant woman, they can now check with several hospitals at one time. The system continues to alert facilities until one of them offers a bed.

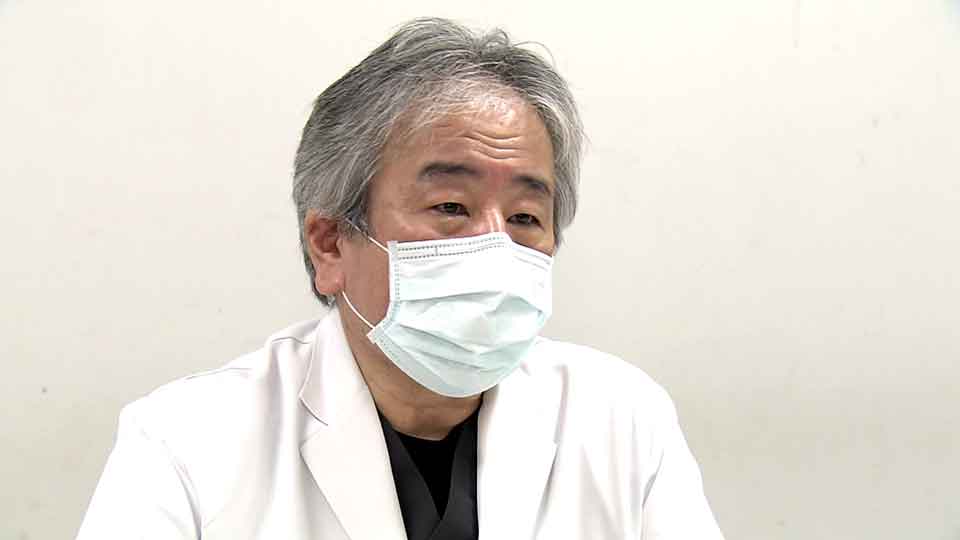

Ohsone Yoshiteru, the director of Chiba University Hospital’s Perinatal Medical Center, says five women have been helped: "We can identify the condition of a infected mother and each facility can decide whether to admit her within 15 minutes."

Limited intensive care beds

While the new measures are helping pregnant women get the help they need, neonatal intensive care (NICU) wards are struggling to meet demand.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, NICU beds were almost always occupied, especially in big cities near Tokyo. The pandemic has made it difficult to find facilities with a vacant NICU bed and a hospital bed for the mother at the same time.

Medical staff need to prepare for the possibility of premature birth or infections in newborns when the mother has the virus. Caesarean sections are being favored for deliveries in those cases, with infection control for medical staff also a consideration.

The United Nations Children's Fund, or UNICEF, reported in 2018 that Japan is one of the safest places to be born. But Ohsone points out that this creates a paradox.

"Japan has one of the highest infant survival rates in the world," he says. "That means the number of days babies spend in the NICU is also high. The longer the bed occupancy, the harder it is to find a bed for new arrivals. We can’t instantly increase the number of NICU beds because we would need more medical staff to cover them."

While officials in some parts of Japan say the Omicron surge appears to have peaked, a large number of patients are still self-isolating at home. That includes pregnant women whose condition and care is of utmost concern.