What is the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons?

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) is the first international agreement to make nuclear weapons illegal. It prohibits the development, production, possession and use of nuclear arms.

The agreement entered into force on January 22, 2021, after securing 50 ratifications. That number has risen to 59 now, though it includes none of the countries that possess the weapons.

Delegates from states that are party to the treaty plan to hold a first meeting from March 22 to 24 in Vienna, although the schedule may change due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, nine countries have notified the United Nations they will attend as observers. Some NATO members, including Germany and Norway, say they may attend too.

The chair hopes Japan will participate

The head of the Austrian Foreign Ministry's disarmament department, Alexander Kmentt, will preside over the meeting, which he says will be "crucial in setting the future direction for the new treaty."

Kmentt said support for victims of the weapons was one of the major items on the agenda, so he is hoping Japan will participate, as the only country to have experienced nuclear attacks.

"Whether or not to participate is for the Japanese government to decide," he said. "But I hope that many states that have yet to ratify the TPNW will come to the meeting as observers."

Hibakusha played a crucial role in the treaty

Elayne Whyte Gomez is a Costa Rican diplomat who was the chair of the negotiating conference for the prohibition treaty.

One of her first moves was to open the debate up to civil participation, allowing people not connected to governments or international organizations to attend the conference. She says the survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, known as hibakusha, played a critical role in this process.

"Let me put it this way, it'll be very hard for me to envision that the treaty that prohibits nuclear weapons could have been achieved without the voices and the living testimonials of the survivors."

International tensions heightening nuclear risk

Supporters of the UN treaty hoped it would give momentum to the push for nuclear disarmament. But five years later, Whyte worries that the threat has grown.

The world's two biggest nuclear powers, the US and Russia, are at loggerheads. China is building its nuclear arsenal, and North Korea continues to launch ballistic missiles.

"We are seeing rising tensions among the powers," says Whyte. "We are at a very difficult moment in the history of the process of disarmament in which we need to see more progress and we need to call on nuclear states to make more progress".

Tale of two treaties

The nuclear powers are firmly opposed to the treaty. The US, Russia, China, France and the UK—who are also permanent members of the UN Security Council—issued a joint statement that supports efforts to prevent the further spread of nuclear weapons. At the same time they maintain that the existence of nuclear arms acts as a deterrence. The statement says they consider "the avoidance of war between Nuclear-Weapon States and the reduction of strategic risks" to be their foremost responsibilities and that "a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought." They insisted they remain committed to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), a different agreement that dates back to 1970, which emphasizes the importance of preventing further spread of the weapons.

It is believed the five powers are concerned the prohibition treaty could replace the non-proliferation agreement as the main focus of the global campaign against nuclear weapons. For those countries, nuclear deterrence is a prerequisite condition for their security policies, and they have no intention of giving up nuclear weapons.

Beatrice Fihn, Executive Director of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), an organization that played a major role in putting the prohibition treaty together, says the two agreements should not be considered mutually exclusive.

"It's just not true that the TPNW weakens the NPT," she says, "and they are perfectly fine to coexist. The NPT is doing fine. The TPNW doesn't harm the NPT. The only thing that harms their NPT is that the nuclear armed states refuse to implement the disarmament obligations, and that has nothing to do with the TPNW. Now that has to do with a nuclear armed state. So when the UK government increases their nuclear arsenal, there is a direct violation of the NPT. That's harmful. When China increases its nuclear arsenals, it's a direct violation of the NPT and it's harming and undermining the NPT."

Citizen activists have crucial role to play

ICAN has been urging nuclear-weapon states that have not ratified the prohibition treaty to attend the meeting in Vienna in March.

On January 22, one year after the treaty took effect, the group called on the French government to participate. Teaming up with NGOs in Paris, it petitioned for support from the French public. The response, however, was underwhelming. Many who were approached to sign were not interested in discussing the issue. Others expressed skepticism. They argued that even in the case of a total ban, some countries would continue to secretly maintain nuclear arsenal.

Nelly Costecalde, an NGO member who took part in the campaign, said one of the biggest problems in France is ignorance. "I think most French people don't even know that the TPNW exists," she said. "The government should at least participate in the first TPNW meeting as an observer and if they continue to criticize the treaty, they should have at least debate with other countries."

Japanese youth play their part

In Japan, the hibakusha are inspiring some young people to get involved in the nuclear abolition movement.

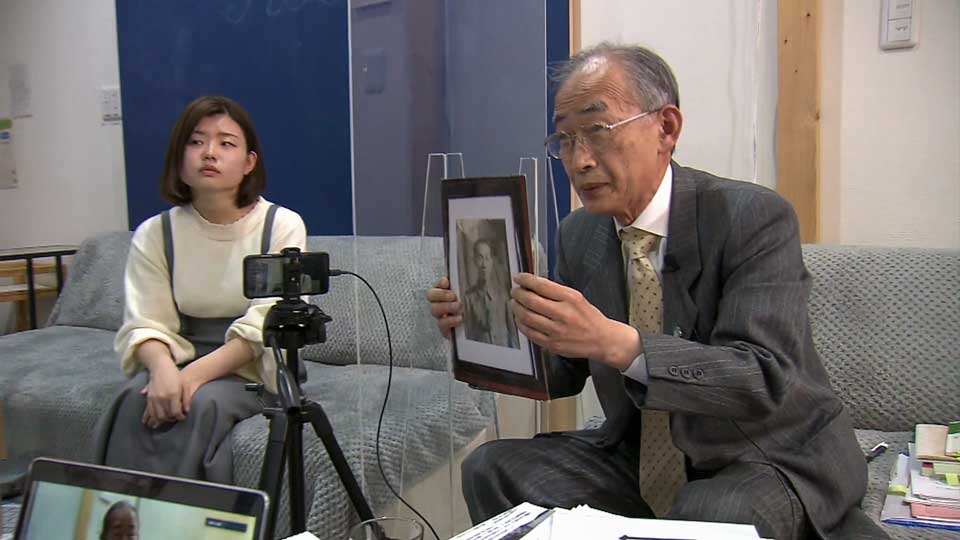

At a recent online event arranged by students in Tokyo, a survivor of the bombings talked with young people about the horrors he experienced.

"Opportunities to listen to their stories are decreasing," said university student Tokuda Yuki. "I feel most young people in Japan aren't interested in nuclear issues. If they listen to the hibakusha, I think more will get involved and start seeing how important it is for Japan to take part in the treaty."

Hamasumi Jiro explained to the gathering that his mother was still pregnant with him when the atomic bomb detonated over Hiroshima. He never got to meet his father, who died in the blast.

All his life, he said, he has suffered from a deep-seated anxiety about how the radiation might impact his health, or the health of his children.

The hardships he has faced have not dimmed his determination to keep fighting. "I'm angry that Japan is not part of the UN nuclear ban treaty. Hibakusha have been telling the world for decades that nuclear abolition is the only way. It's our duty to lead other countries toward that goal. I won't give up."

Tokuda says at the very least, the government should attend the Vienna meeting in the capacity of an observer. "It's really strange that the only country that has suffered from atomic bombings hasn't joined the treaty," she says. "We should be leaders on this. I believe that if Japan chooses to get involved, other countries will be encouraged to follow."