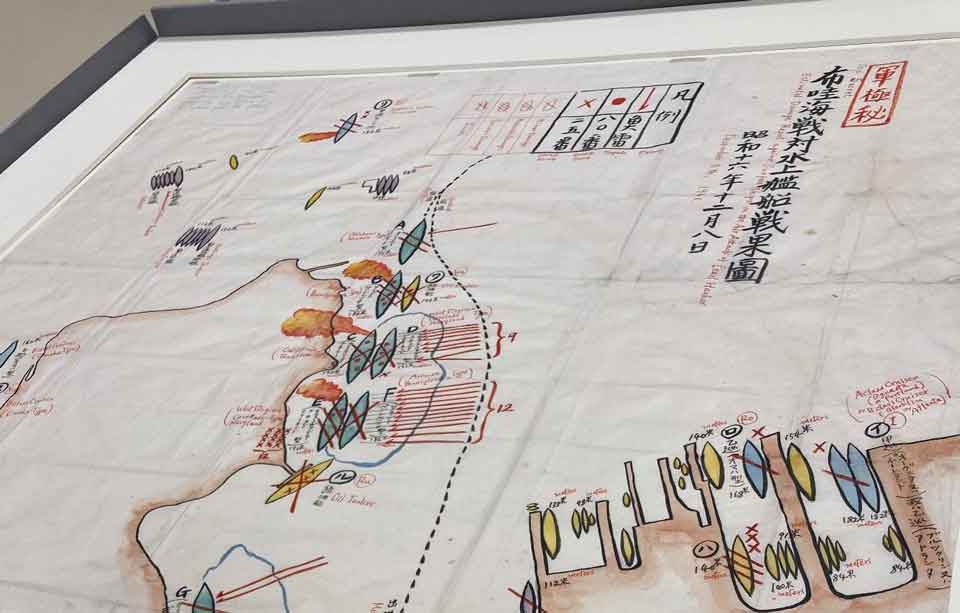

The vivid map pictured above was drawn by Fuchida Mitsuo, the Imperial Japanese Navy captain who led the air raid on December 7, 1941. Showing details of the damage to US forces, the map was used to brief Emperor Hirohito about the attack. It now sits in the Library of Congress in Washington, DC.

The raid sunk or damaged 21 warships and killed 2,403 Americans, including civilians. President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared war against Japan the next day during a speech to Congress. He famously referred to December 7 as a "date that will live in infamy."

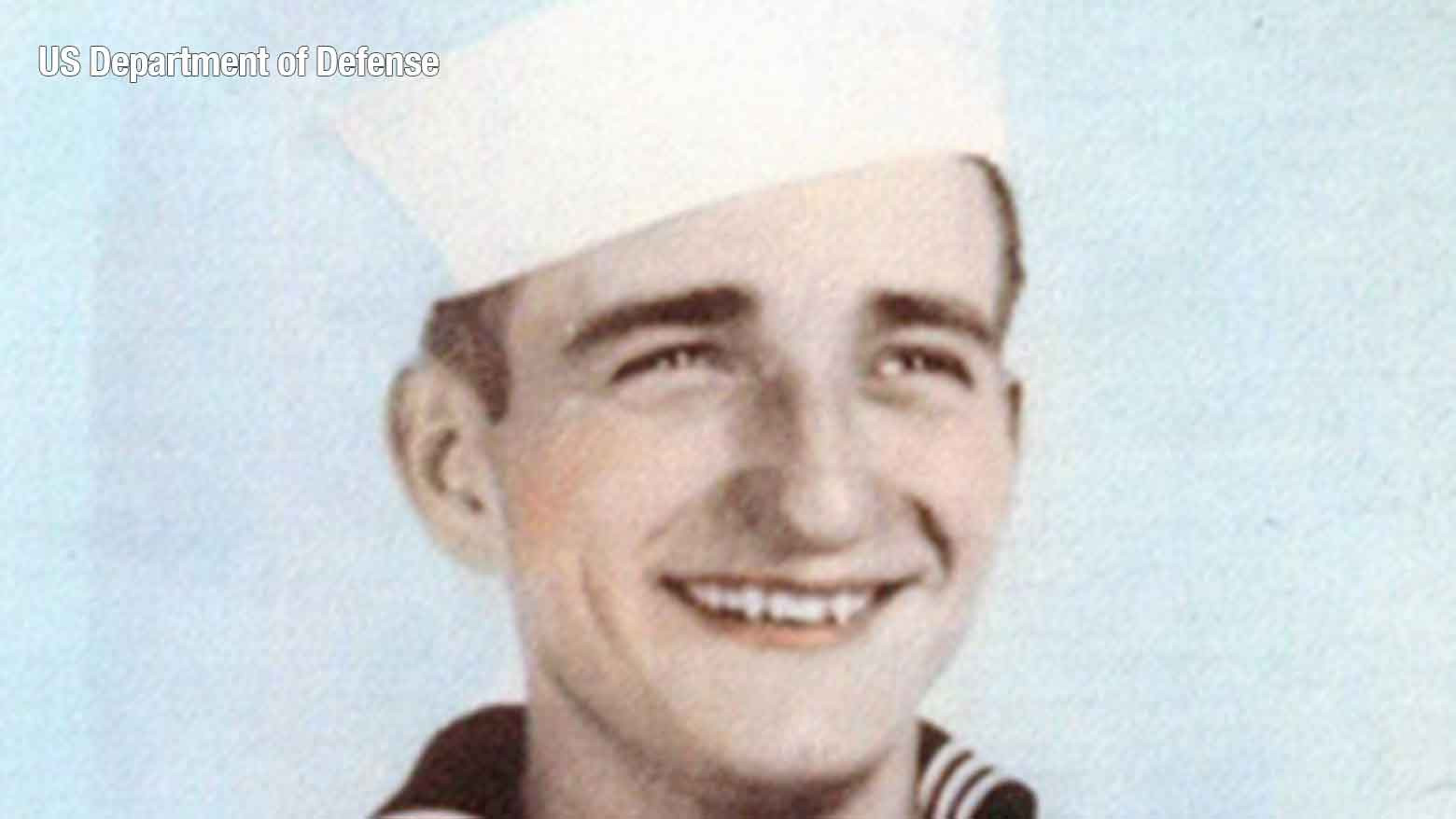

In October last year, a long-awaited funeral for Navy Seaman 1st Class Wesley Graham was held at a cemetery in Augusta, Michigan. Graham was just 21 years old when he was killed in the attack.

One of his nieces, Karen Berzins, broke down in tears at the ceremony.

"This is where he was inducted from and this is where I wanted him to be," she says. "Wesley was born in Michigan, and he is finally being laid to a final rest in Michigan. So, I’m happy. It's miraculous that he can be home after 80 years."

Graham’s remains were identified after nearly eight decades because of the military’s ongoing efforts to test the DNA of Pearl Harbor victims.

Graham was serving on the battleship USS Oklahoma, which was sunk by a torpedo during the attack. The ship was salvaged two years later, but the remains of around 400 crew members trapped inside could not be identified. They were buried together in a cemetery in Hawaii.

A turning point came more than 70 years later. In 2015, technological advances led the US government to exhume the remains and begin DNA testing.

After learning about the plan, Berzins provided her DNA to the military. But she never heard back and was on the verge of giving up when, in 2020, she got a call notifying her that her uncle’s remains had been identified.

Berzins is one of the lucky ones. About half of the remains of those who died in the attack are still unidentified.

Painstaking work

The US military makes every effort to collect the remains of, and perform DNA testing on, troops who die overseas. It still classifies about 80,000 of them as "unknown soldiers."

One of the facilities where the work takes place is Offutt Air Force Base in Omaha, Nebraska. The base currently houses 100 sets of remains. Bones that have been identified — from skulls to hands to feet — are lined up in an orderly manner, and protocols are strict: out of respect for the deceased, no cameras are allowed.

The remains of the approximately 400 unidentified sailors from the Oklahoma include 13,000 bone fragments. After cataloging all the different pieces, forensic anthropologists meticulously gather the bones that belong to the same person.

The remains are covered in oil that leaked from the battleship, and even 80 years later, the odor clings for days to the hair and clothing of the forensic anthropologists who have been working on the project.

The process is painstakingly difficult. It took a long time to sort through the remains, as they had been mixed together when being disinterred. What’s more, the soldiers’ medical records, which could have provided useful data like their height and any dental work, were lost when the ship sunk.

Despite these challenges, the forensic anthropologists have, after six years, managed to identify 361 unknown soldiers — more than 90 percent of the remains.

"Families need closure"

As the work continues, one exception is the USS Arizona, the battleship that suffered the most casualties. More than 1,200 sailors died on the ship — about half of all those killed in the attack.

Because the Arizona was so heavily damaged, it couldn’t be salvaged. The ship is considered the final resting place for 985 sailors whose remains are still inside. The government has no plans to try to identify them.

As a result, the relatives of these crewmembers feel as though the pain caused by the Pearl Harbor attacks has never ended.

Randy Stratton of Colorado is one of them. His father was a crewmember on the Arizona who survived the attack but sustained heavy injuries, with burns over 65 percent of his body. Until his death in 2020 at the age of 97, he never forgot about his comrades who lost their lives that day.

"Family members deserve closure," Stratton says. "Those soldiers are not unknowns; they have a name. And we're going to find out what their names are in honor of these men."

Stratton stays in touch with other USS Arizona families who want their loved ones to be identified, and he’s urging the government to identify the remains, especially of the 80 or so bodies that were recovered and buried but never identified.

Some things change, others don’t

Some of the soldiers who lived through the war held Japan in great contempt even after the fighting ended. Some refused to buy Japanese products or eat Japanese food for the rest of their lives.

However, neither Berzins nor Stratton hold ill feelings.

"Things change and people move on," Brezins says. "For me to not feel OK about a Japanese person would be wrong because they are not to blame for what happened 80 years ago. You’re not responsible for what generations before you have done. We remember what happened so that the bad things in history we don’t repeat, and we learn from them."

Other families who lost their relatives at Pearl Harbor have shared similar sentiments. Perhaps the passage of 80 years has brought about some change. But one thing that remains constant is the desire to bring their family members home.