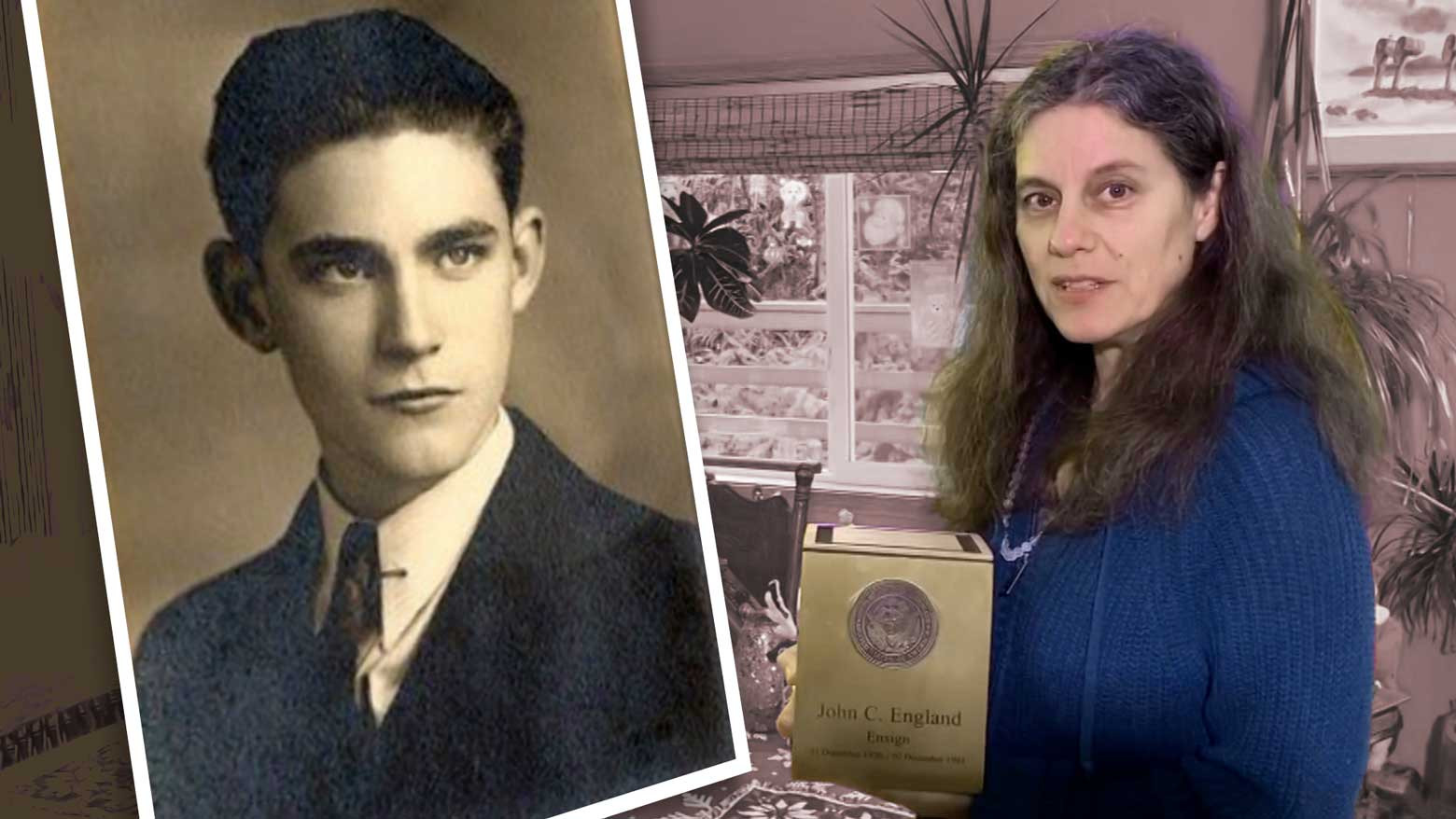

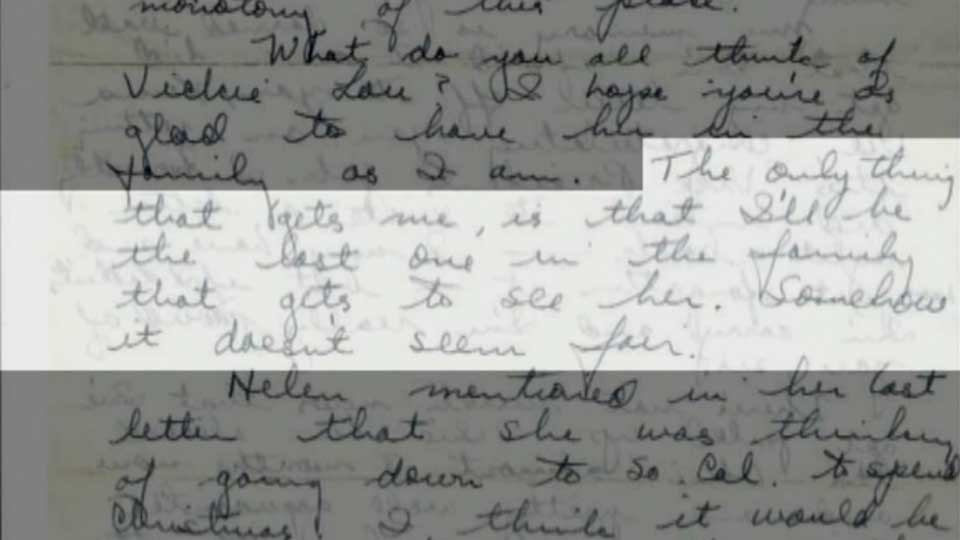

In his last letter to his parents, US Navy Ensign John Charles England asked about his newborn daughter. "The only thing that gets me is that I'll be the last one in the family that gets to see her," he wrote. "Somehow it doesn't seem fair."

England never got to see his daughter. He died two weeks later in the attack on Pearl Harbor.

England was one of 429 men who were killed when Japanese torpedoes blasted through the hull of the USS Oklahoma, causing it to capsize. He initially escaped to the top of the vessel, but went back inside three times to help others. On his fourth rescue attempt, he didn't come out.

He was just four days away from his twenty-first birthday.

Death becomes taboo

The military notified England's family that he had gone missing in action, and that his remains could not be recovered. Such was the grief among his relatives that even talking about him became taboo.

"We suffered in a way that only families left without a sense of closure could possibly understand," says England's granddaughter, Bethany Glenn. "It's a sadness that seems to drape over the generations."

After her mother died in 2002, Glenn received boxes containing letters, yearbooks, pictures and other mementos of her grandfather's life. She spent weeks combing through them, every day learning something new.

She says, "I felt like it was really the first time that I got to know him. I learned that he was a very well-loved kid. He was the class president in high school. He was just one of those guys that everybody loved."

The more she delved into her grandfather's short life, the more determined she became to bring him home.

"JC" found in Hawaii

Despite what the military told the family, the remains of John Charles England, or "JC", were eventually identified and buried alongside other unknown soldiers in a national cemetery in Hawaii.

When Glenn and her family found out, they resolved to do whatever they could to get them back. In 2016, after an eight-year effort involving DNA identification, they received his skull. It was flown from Hawaii in a casket wrapped in the stars and stripes of the US flag.

Seventy-five years after the Pearl Harbor attack, JC had finally made it home. There was a solemn military funeral, where the family laid his remains to rest alongside those of his parents.

Glenn describes the long-awaited moment as a liberating experience: "To be able to have conversations, talk about what he did and feel good about it and bring him back alive so we can give him the proper burial that he deserved and a proper send-off to the universe – that really felt great."

The ordeal was finally over for England's family, but Glenn wanted others to experience the same sense of release that she did.

Work of NPO inspires joint mission

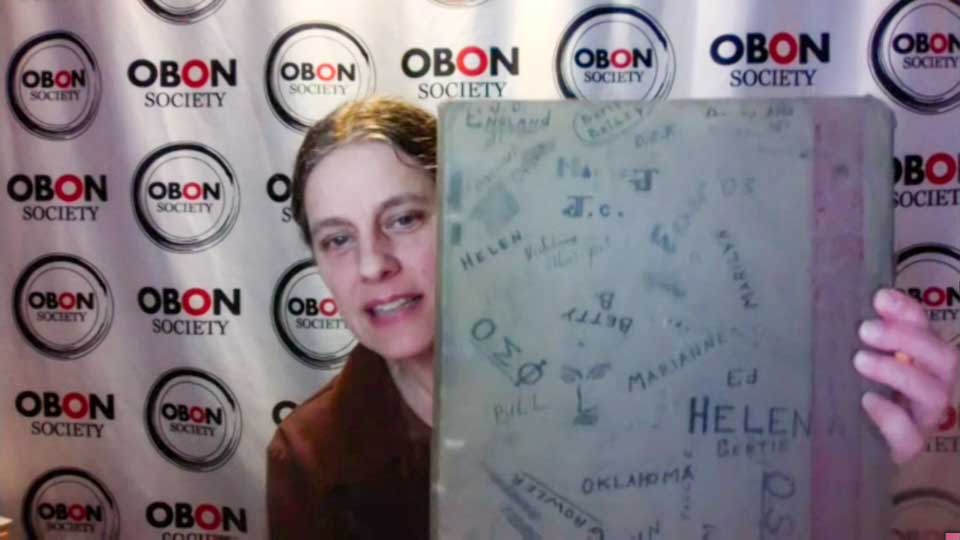

That was when she found out about OBON SOCIETY, a US-based NPO that supports the families of men who never made it back to Japan from the battlefields of World War Two. Members of the group help return personal items such as flags that were souvenired and taken to the United States.

The co-founder, Keiko Ziak, lost her grandfather in the war. It wasn't until many years later, after getting his flag back, that she felt peace.

Glenn says she was "blown away" by the work that Ziak was doing. She got in touch, and before long the two women were embarking on a joint mission to heal wounds on both sides of the conflict.

Over the past decade, they have helped return more than 400 flags to families in Japan. "I do not think there is any difference in the item that is being returned, whether it is bones or a flag," says Glenn. "The end results are the same for every family – they go home with closure and that is what is most important."

OBON SOCIETY has been expanding its efforts beyond Japan and the United States. In the lead-up to the 80th anniversary of the start of the Pacific War, the group accepted an invitation to address an online gathering arranged by a club in London.

Message resonates in Europe

OBON's message resonated with young German Air Force Cadet Philipe dos Santos, who has been researching World War Two soldiers from European countries who have never been accounted for.

He describes the group's work as, "a way of making peace and closing peace too – not only closing the unknown destiny of that soldier who fell somewhere in the Pacific, but also to make the world a little better, too."

In November, Glenn learned that the rest of JC's bones had been identified and sent home, just one day before the 80th anniversary of Pearl Harbor. She made a small shrine for her grandfather, and put the urn containing his remains next to his photo. She says the experience has provided a powerful sense of finality.

Sending off 'the kid'

Glenn made special plans for the Pearl Harbor anniversary. Instead of attending a ceremony or watching war-related TV specials, she would put on JC's favorite movie, "Gone with the Wind," with him by her side. Later, she and her family would take him on a road trip to visit the places where he grew up, and meet people whose lives he touched.

Glenn explains, "The first time, when we buried his skull, we had a very military funeral, which was good in that he was honored as the war hero. But this time around, we're going to celebrate the kid in him, the playful and the funny and fun-loving kid that he was."

Glenn points out that the families she's helping in Japan represent a tiny fraction of the people impacted by conflicts all over the world. At the same time, she says every case of closure brings humankind a little closer to peace.

Also watch: Families Find Path to Reconciliation (08:37)

Dec.8, 2021

A-Bomb Survivor's Lasting Legacy (08:42)

Dec.6, 2021

Reexamining Wartime Discrimination in Hawaii (12:03)

Dec.7, 2021

Peace Fuels Bond between Children of Sister Cities (08:44)

Dec.9, 2021

Warning Signs Ignored on the Path (09:49)

Dec.10, 2021