With world leaders gathering at the COP26 summit in Glasgow, it's becoming increasingly clear that we're already living with the consequences of climate change. U.S. journalist David Wallace-Wells, in his famous 2017 essay "The Uninhabitable Earth," broke down some of the effects we're dealing with: a 50-fold increase in extreme temperatures since 1980; collapsing ice shelves in the arctic; 10,000 deaths per day — right now — due to fossil-fuel pollution.

Scientists with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concur with his reporting. Their recently released Sixth Assessment Report found, among other things, that the past decade was the hottest in 125,000 years, and global sea levels have risen eight inches over the last century, with the rate of increase doubling since 2006.

On the West Coast of the United States, residents are already living with one of the most destructive consequences of climate change: increased wildfires.

Two fires in three years

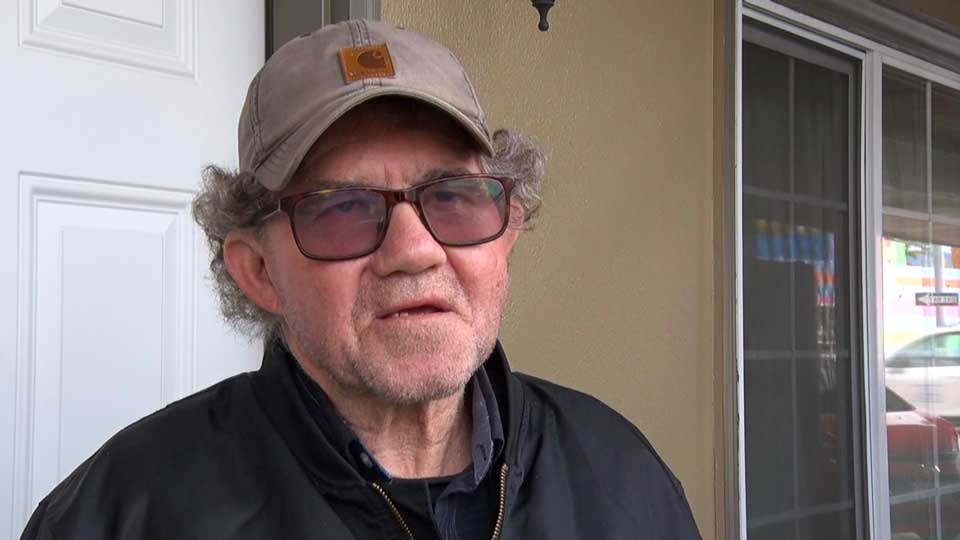

Fred Bailey lives in a converted motel room in Medford, Oregon. The room was provided to him by a local nonprofit called Rogue Retreat, which was originally founded to assist homeless residents of Oregon's Rogue River region. But after a series of wildfires devastated the area, the group decided to focus some of its efforts on helping survivors.

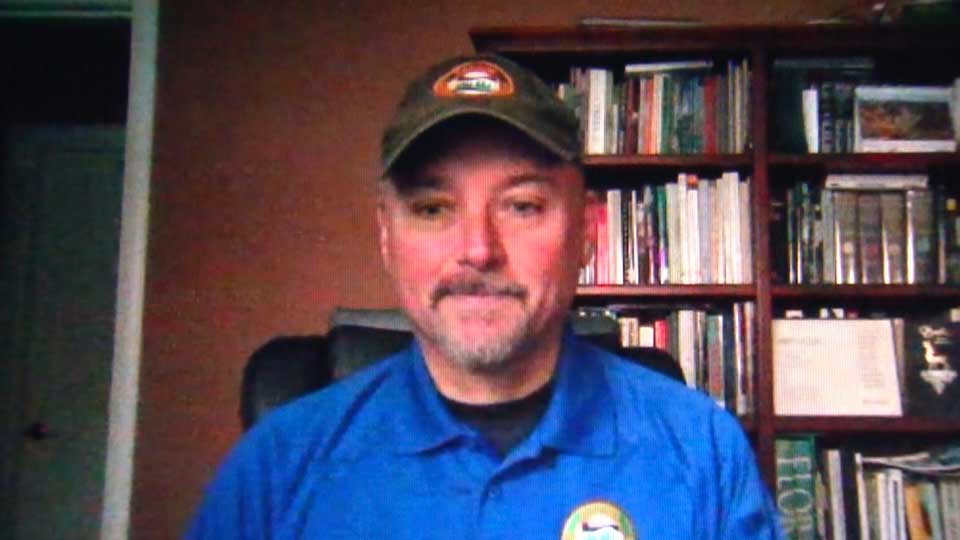

"We were already in a rental crisis in this community, so there wasn't enough affordable housing before the fires," says Matthew Vorderstrasse, Rogue Retreat's development director. "And so when we ended up losing 2,500 additional homes [in the fires], it really exacerbated the housing crisis that we are in."

Bailey moved into the motel after last year's Almeda Fire destroyed his trailer home. But that wasn't his first experience with such a tragedy: His wife died in a fire in the same area in 2017.

"We've all been through a lot," he says. "We were doing really good until all this happened. I just try to keep my mind off of it and go do other things, you know. Being around people, I try and go to church three times a week just to be around people."

Year-round fire season

Bailey's experiences — losing a loved one, losing a home — are, sadly, becoming more common on the West Coast. Data provided to NHK by the Oregon Department of Forestry shows a three-fold increase in the average number of acres burned each year since the 1990s.

"These dry summers, preceded by a dry spring, can create conditions that make it very difficult for firefighters to stop and control a very large fire once it gets going," says Jim Gersbach, a public affairs rep for the forestry department. "We have seen a rise, an increase in the amount of acres burned, pretty consistently decade by decade. And we do feel that a warmer climate globally is having an impact in Oregon and that we are seeing these drier conditions."

Up and down the West Coast, the picture is similar. Eighteen of the 20 largest wildfires in California's history have occurred during the past two decades; the top eight have all come during the past four years. The US Department of Agriculture recently announced that it has done away with the concept of "fire season," because a hotter climate means fires are burning all year round.

In California, that is literally true: The National Park Service (NPS) tells NHK that trees in Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Park that caught fire during a wildfire last year were still burning when park rangers returned to the forest this year. Tony Caprio, a fire ecologist for the NPS, says he's only seen that phenomenon one other time in his career, after a devastating fire in the park in 2012.

2.4 degrees

Regardless of any actions we might take today, the climate problem is certainly going to get worse. Human activity has already warmed the planet by about 1 degree Celsius. If every nation meets its COP26 targets for emissions reductions by 2030, that will result in a rise of about 2.4 degrees, according to a recent analysis of the final agreement.

But climate scientists consider any warming above 1.5 degrees to be potentially disastrous for human society. And it's unlikely that every nation will live up to its COP26 pledge, given that most countries are failing to meet their emissions-reduction promises from the Paris Agreement.

The burden to reduce emissions falls heavily on countries like the US that have historically produced the most pollution. Countries that have undergone swift development, like China and India, must also quickly pivot to clean energy if we hope to keep global warming to a manageable level. What we do over the coming decades, and whether we're able to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels, will determine what kind of world we pass on to future generations — in fact, it might determine whether there's anything left to pass on at all.