At first glance, Guantanamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba looks just like any other US military facility. There's a McDonald's, a shopping mall, and a bowling alley alongside ordinary-looking institutional buildings.

In the middle of these sleepy surroundings, though, sits the detention camp that's become one of the most notorious prisons in the world. The Guantanamo base has been widely criticized for being the site of human right abuses, including torture and indefinite detention.

Soon after the 9/11 attacks, Guantanamo became one of the front lines — along with Afghanistan and Iraq — of the US government's "War on Terror." It was meant to house the "worst of the worst."

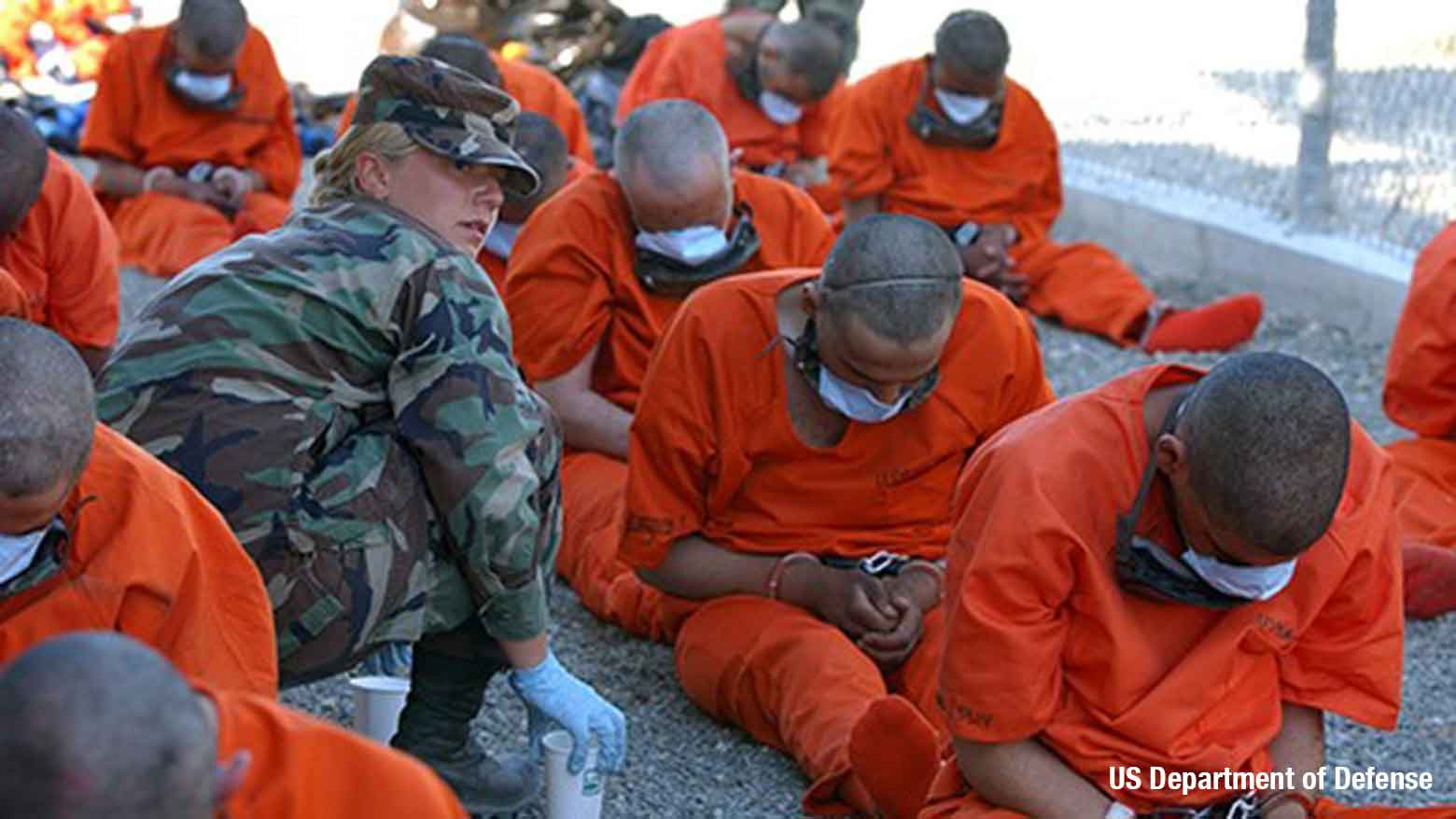

When we visit almost 20 years later, a salty breeze blows off the Caribbean and overflowing weeds poke through the metal fence of Camp X-Ray, where the iconic pictures of the first detainees — wearing orange jumpsuits, shackled and blindfolded — were taken.

All video footage that we shot was subject to inspection before we left, and a good amount had to be deleted for "security reasons."

"I don't know what it means to be in my twenties"

Mansoor Adayfi wears a bright orange scarf, the same color as the jumpsuits worn by Guantanamo detainees. He spent 14 years imprisoned in the facility and was released without ever being charged. He was 33 years old when he became a free man in 2016.

"I don't know what it means to be [in my] twenties," he says in the fluent English he learned in Guantanamo. "The prime time of your age is lost there."

"What would a normal kid or boy in [his] twenties do? Be it job, married, kids, or start a business. We did not have any of that." Instead, his twenties were nothing but torture, he says.

Adayfi was born in Yemen, and his goal of studying abroad led him to visit Afghanistan as a research assistant in 2001. According to his account, he was captured by a local warlord and handed over to the US. He believes he was sold to the CIA for a bounty that the Americans set up for anyone suspected of having ties to al-Qaeda or the Taliban.

Interrogators, who mistakenly believed Adayfi was a former Egyptian army commander involved in recruiting for al-Qaeda, besieged him with questions: "Where is bin Laden? Where are the nuclear targets? What is the next target?"

"I didn't know," Adayfi says. "[They] just force you to repeat the answer they want to hear."

His denials were met with physical and psychological abuse: beatings, stress positions, genital touching, cavity searches. One of the abuses was dubbed the "Frequent Flyer Program." It was designed to deprive detainees of sleep by subjecting them to a beating in their cells, then leaving them alone just long enough to fall asleep before again being beaten, restrained, and transferred to another cell. This process lasted weeks.

After 14 years, Adayfi was released with neither an apology nor an offer of compensation from the US government.

He was unable to return to Yemen because of the ongoing civil war. US forces sent him instead to Serbia, where authorities agreed to accept him. They delivered him there just as he had been brought to Guantanamo — blindfolded and in shackles.

"Miscarriage of justice"

Adayfi isn't the only Guantanamo detainee whom the US government failed to charge with a crime or involvement in terrorist activities. In fact, his case is similar to most. A former US military official told us the reason: Detainees could not be charged based on testimony they provide under duress.

In 2003, Stuart Couch was appointed as a prosecutor at the military tribunal for a high-profile case against a Guantanamo detainee. Outraged by the 9/11 attacks, he wanted justice to be served and eagerly accepted the assignment. The copilot on United 175, the second plane to strike the World Trade Center, was his close friend.

"We were keenly aware that the legal prosecution effort we were conducting was as much a way of prosecuting the war on terror and going after our enemies, as in other respects, ground combat," he says. "The enormity and the historical context of it was significant for me."

But things took a surprising turn on his visit to Guantanamo, when he happened to witness the abusive treatment of other detainees. In a dark interrogation cell, he saw an inmate handcuffed, shackled to the floor, and blasted with heavy metal music and strobe lights.

"The moment I saw it, I was outraged," he says. "I was shocked. And I was angry. I was disgusted because somebody above my pay grade said, 'Let's do something outside the box.'"

"This is a country that believes in the rule of law."

As Couch did some digging, it became clear that confessions from detainees were obtained through mistreatment and abuse and therefore not reliable enough to hold up at trial.

He knew abusive interrogation techniques did not work because he had experienced them firsthand. As a Marine pilot, he underwent training on how to deal with being captured by the enemy. The exercise involved torture-like psychological and physical abuse.

"There was not sufficient evidence to convict him," Couch says of the detainee he was assigned to prosecute. He wholeheartedly believes in the old legal saying: "There's one thing worse than a guilty man going free, and that's an innocent man going to a jail."

"[The Guantanamo legal system] has been unsuccessful at the least, and a miscarriage of justice at the worst," he says, adding that the military tribunals were a "facade" to justify cruel interrogations instead of holding accountable those responsible for the 9/11 attacks.

The numbers bear this out. Of the 779 Guantanamo detainees held since 2002, more than 730 have been released. Of the 39 that remain, only 12 have been charged in the military tribunal and just two have been convicted.

"The one who laughs in the end laughs the most"

That raises a question: Has Guantanamo made the US safer?

Adayfi has an answer: "No, I don't think so."

He believes Guantanamo has only incited anti-American sentiment among some Muslims. He says militants have used the prison as an example of how the US treats people of the Islamic faith. The orange jumpsuits have become a symbol of anti-American sentiment; indeed, the militant group ISIS dressed foreign journalists in similar garb before executing them.

Last month's events in Afghanistan underscore that point. On the day the capital Kabul fell under Taliban rule, a former Guantanamo detainee, Gholam Ruhani, was among the fighters who stormed the presidential palace.

Another former detainee reposted video and took to Twitter to mock the US. "When Ruhani was in Guantanamo, he told a US soldier, 'The battle is not over yet. The one who laughs in the end laughs the most.'"

Among the Cabinet members in the Taliban's interim government, four are former Guantanamo inmates.

According to the US government, 17 percent of detainees have "return[ed] to terrorist activities" after their release.

"Guantanamo hasn't finished with us yet"

The stigma of Guantanamo still haunts former detainees. The Serbian government has Adayfi under constant surveillance, and a local newspaper once referred to him as a "terrorist." He's been restricted from traveling or obtaining a driver's license. When some new acquaintances realize Adayfi is a former detainee, they ask him to delete their numbers from his mobile for fear of getting into trouble.

"That name [Guantanamo] implies you deserve to be there, you have done something, [and] that you are a terrorist," he says. "At Guantanamo I was fighting for freedom, but here I am fighting for my life."

"Guantanamo has not finished with us yet."

"You have the choice"

Adayfi is trying to make up for the time he's lost. He goes to college in Belgrade — something he long aspired to do — and is working on a thesis about the reintegration of former Guantanamo detainees into society.

He says he doesn't feel resentment against the US government, but that "those emotions we have — anger, hate, grudge — they all exist in our heart."

"You have the choice," he says of moving forward. "[If you] imprison yourself at this stage, you are destroying yourself."

At the end of our interview, Adayfi explains that he always wears a bright orange scarf, reminiscent of the orange jumpsuit, because if he comes to hate the color, it means he is still imprisoned by Guantanamo.

"The orange is just a color," he said as he touches the scarf.