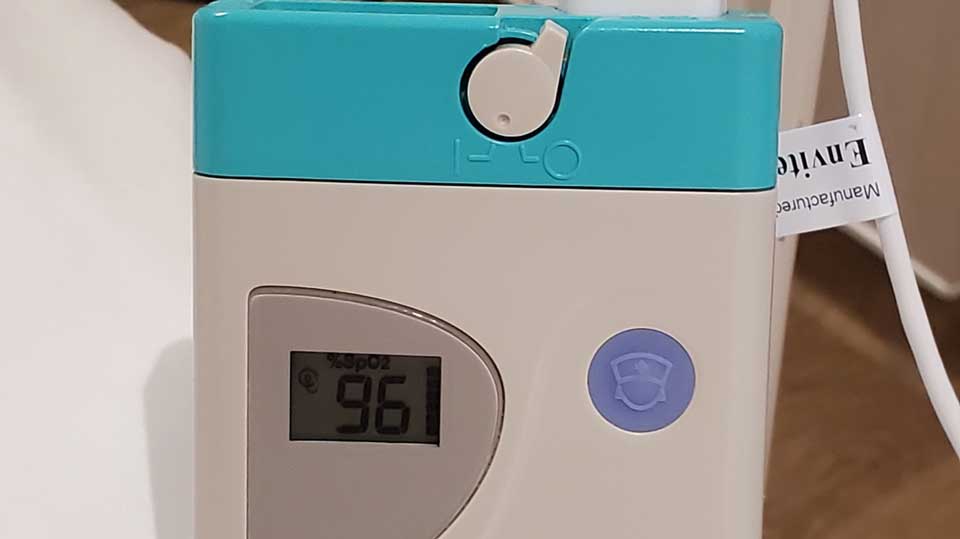

Electronic sounds beep through the night. A device to monitor my blood oxygen saturation level is clamped to my fingertip. Aged 53, I find myself hospitalized for one month with coronavirus pneumonia. For almost a week, I was in a medically induced coma as a ventilator breathes for me. Here is my story, day-by-day:

The beginnings of COVID-19

Thursday, July 15

Number of new cases in Tokyo: 1,308

I feel heavy, with pains in my back, but no fever. I attend a regular online editorial meeting about an online NHK politics magazine. Because I received my first COVID-19 vaccination yesterday, I attribute my symptoms to the shot.

Saturday, July 17

Number of new cases in Tokyo: 1,410

I wake up with a temperature exceeding 38 degrees Celsius. Fearing it is the coronavirus, I visit my regular medical clinic to take a PCR test. The doctor tells me: "We will inform you of the result in one or two days. Take good care of yourself."

I live alone in an apartment in Tokyo because my wife came down with an illness several years ago and is cared for at her parents’ home. I usually visit her on Sundays. I explain to my father-in-law that I won’t be coming this weekend. I take some medicine, rest in bed, and cook some meals. My appetite is normal.

"You tested positive."

Monday, July 19

Number of new cases in Tokyo: 727

I can’t stop thinking about whether I have coronavirus. My phone rings in the morning and it’s the doctor from the clinic. "You tested positive. We will inform the ward’s public health center."

No one that I’m in close contact with is infected, and I have no idea how I’ve been infected.

An official at the health center instructs me to stay home until July 27. I tell them that I would prefer to recuperate at one of the hotels that has been repurposed for coronavirus patients. But the official says my voice sounds like I am well and asks me to remain at home. I get only a vague answer when I ask if the hotel rooms are fully occupied.

I report to the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG) follow-up center that monitors the condition of people convalescing at home. I need medicine to bring down my fever, so I consult with a doctor online. It’s a service that I’ve been referred to by the public health center.

Soon afterwards, I get a call from a pharmacy to tell me my medicine will be delivered at around 3pm. After the designated time, I check that there is no one near the mailbox, and step outside to clear it. I’m in a relatively good state.

Tuesday, July 20

Number of new cases in Tokyo: 1,387

I receive a delivery of items I ordered online, including frozen food and bottled water. To avoid contact, I tell the delivery person to leave the package outside the door. A colleague also drops off some supplies that I collect in the same way. They’ve included a good luck charm from a nearby shrine. I recall we had made a New Year visit there together.

Waiting for monitoring equipment

Wednesday, July 21

Number of new cases in Tokyo: 1,832

My fever of over 38 degrees persists, but it comes down when I take medicine. Disappointingly, I haven't received some items the public health center said would be delivered by today. They include a pulse oximeter to measure my blood oxygen saturation level.

I call to check and am told to expect delivery by Friday. I am growing increasingly anxious as I am unable to monitor key data that relates to my condition.

"Get me to hospital"

Thursday, July 22

Number of new cases in Tokyo: 1,979

My waking temperature is more than 38.5 degrees. I have a headache and have lost my sense of smell. I have trouble cooking a meal in the kitchen and it’s clear that my condition is worsening.

My mother, who lives far away in Nagano Prefecture, calls. She is worried about me and has sent me some home-cooked food. I have to tell her that I’ve lost my sense of smell and taste – and I can barely tell the difference between vegetables and meat.

I check my temperature a total of 13 times. My fever stays high and my breathing is getting shallow. I file a request for hospitalization with the public health center, but by the time I call, arrangements for today have finished. I’m told I need to wait until tomorrow. I feel exhausted, and frustrated about the delay in handling my request. I am also concerned that my case won’t even be dealt with tomorrow, so I call the TMG hotline. Their advice is to call an ambulance if I get worse.

I wonder what is happening to my body. I’ve never had a fever last this long. I am 170 centimeters tall and weigh 84 kilograms. At medical checkups, doctors always encourage me to lose a little weight. I am a bit out of shape partly because I had surgery on my right knee a while ago. Some time back, my blood pressure was high, but it has been normal for about five years. I quit smoking 18 years ago. But I drink alcohol at home almost every day, except of course since I developed this fever. I don’t have any underlying conditions and, until now, I have never experienced any serious illness.

My body temperature remains at 38.5 degrees or more. I am unbearably hot, so I drink a lot of water and lower the temperature on the air conditioner. Nothing’s helping. I put icepacks on my neck and armpits, and the ice melts fast.

I feel like I can’t move anymore. I am struggling to understand why this is happening and how the virus is raging through my body. I desperately want to be hospitalized. Shortly after 7 p.m., my temperature tops 39 degrees. I consider calling an ambulance, but stop short when my fever comes down a little. I try to sleep, but can’t.

Calling an ambulance

Friday, July 23

Number of new cases in Tokyo: 1,359

Around 1 a.m., my temperature is back to 39 degrees. I decide to call an ambulance at 1:20 a.m. It arrives about 25 minutes later. Three members of the ambulance crew arrive wearing protective gear. They check my blood pressure and blood oxygen saturation level, which is 92 – well outside the healthy range of 95-100. The crew says they will work out where to transport me, but the process takes a long time.

It is an agonizing wait. The crew asks me to reconfirm that health officials told me to call an ambulance. My brain is foggy but I wonder what would happen if I wasn't able to do that. I overhear one of them saying, "The ward is arranging hospitalization", and things start to move. I am in the ambulance with sirens blaring shortly after 3 a.m.

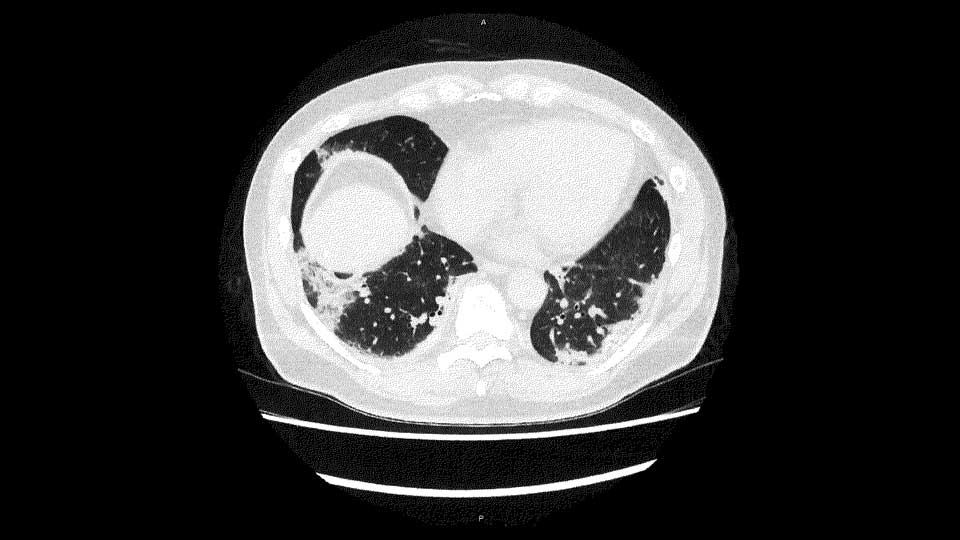

My first ambulance ride lasts about 15 minutes. It seems like I am being taken through a hospital entrance set aside for coronavirus admissions. I undergo a series of examinations, and a doctor has a grave tone when she explains: "You have developed pneumonia due to coronavirus disease. You will be hospitalized to receive treatment." I tell the doctor that I understand and appreciate the decision. The doctor says I have been diagnosed with pneumonia because parts of my lungs appear white on CT scan images. She explains that inflammation appears white, while normal parts are dark.

The hospital staff who are in contact with COVID-19 patients like myself are all wearing protective suits, including face shields and goggles. There is even a person tasked with operating the elevator. I am taken to a COVID-19 ward shortly after 4 a.m. My room has space for four patients, and I am one of two.

Treatment plan

Saturday, July 24

Number of new cases in Tokyo: 1,128

The treatment for pneumonia begins in earnest. The plan that’s outlined has me in hospital for one week. The inflammation is going to be contained with drugs such as steroids, and nasal tubes deliver oxygen to make breathing easier.

I ask the doctor if I'm infected with the Delta variant. He replies, "We don't check which variant it is, because that doesn't affect treatment." I accept that explanation. The back pain I had earlier has disappeared and I feel a little more comfortable. But my blood oxygen saturation level remains low.

Pneumonia advances

Sunday, July 25

Number of new cases in Tokyo: 1,763

The doctor comes to me with the result of a new CT scan. I wasn't expecting what he is about to tell me: there is inflammation in much of my lungs and there is a possibility I will be transferred to the ICU. On his way out he tells me, "Pneumonia caused by the coronavirus advances at a furious pace." His words hit hard and my anxiety goes through the roof.

Relocated to ICU

Monday, July 26

Number of new cases in Tokyo: 1,429

I am instructed to lie face down to allow my lungs to widen which should make it easier for me to breathe. But my blood oxygen saturation level is 86 and falling. My condition does not improve even after the oxygen supply is increased.

In the evening, I am moved to a COVID-19 ICU where the staff are wearing so much protective gear all I can see is their eyes.

Will I ever wake up?

Wednesday, July 28

Number of new cases in Tokyo: 3,177

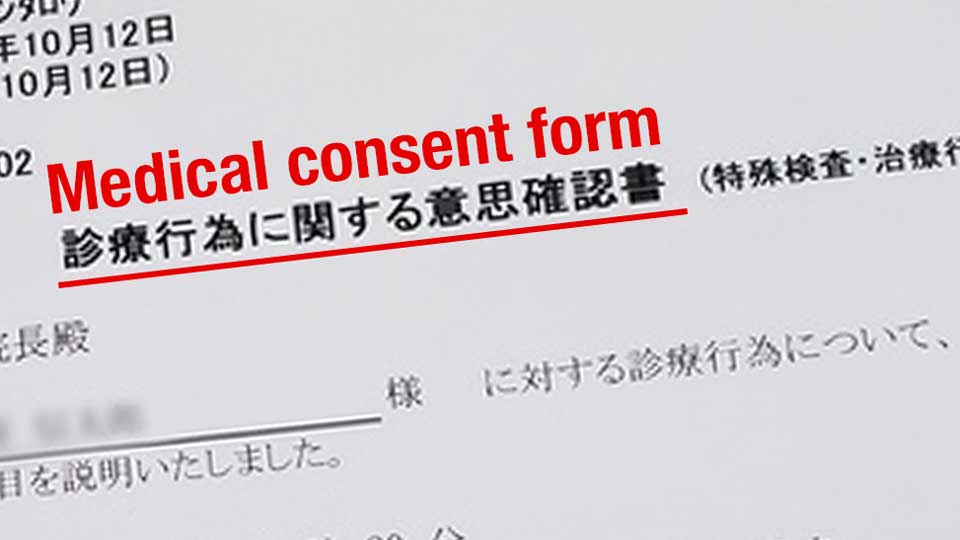

The atmosphere is tense in the ICU, but nothing has prepared me for what I am about to hear: "You have severe pneumonia so we are going to put you on a ventilator for treatment. To relieve the pain of intubation, we will administer sedatives to put you to sleep."

I ask how long the induced coma will last: "It depends on the patient, but usually a few days. Please sign this consent form."

When I contemplate what lies ahead, I am paralyzed with fear. Will I wake up alive? I have never felt more scared in my life.

I have a conversation with a nurse that I don’t remember myself but is related to me later. I tell her that I’m involved in NHK’s election coverage and explain that I hope to be well in time for the August 22 Yokohama mayoral election.

With that, I am sedated and placed on a ventilator. That means I am listed as one of the growing number of people classified as seriously ill with coronavirus.

As the ventilator assists my breathing, anti-inflammatory drugs and nourishment are delivered through an IV line. There are tubes inserted into my stomach and ureter, and my legs are covered by a massage device that prevents blood clots.

Later, I ask a doctor what kind of condition I was in. She says: "In your case, pneumonia had worsened and you were unable to breathe properly. We put you on a ventilator because we judged that otherwise your entire body would be affected by hypoxia and your life was in danger."

Imagine what could have happened if I had been forced to wait longer to be hospitalized. It’s a scary thought.

Regaining consciousness

Monday, August 2

Number of new cases in Tokyo: 2,195

When I wake up, I can see many doctors and nurses. I have been sedated for six days. "The condition of your lungs has significantly improved. You put up a good fight. This is good news."

The hospital has notified the emergency contacts I listed - my parents and my supervisor at work - that I have come off ventilation. During that time, the doctors and other staff reported my condition in detail, over the phone. Because ventilated patients cannot communicate themselves, family and other close contacts receive frequent updates.

While I feel grateful for the care I am receiving and for the thoughtfulness of the people looking after me, I am painfully aware of the burden I am placing on hospital staff. One of my problems is that I have lost my sense of date and time. There is no clock in the hospital room. Because I handed in my watch and smartphone, I keep asking the nurses what time it is.

I realize the Tokyo Olympics must be in full swing and ask a nurse about the Games. She turns on a television for me. I try to watch but it’s too much and I end up switching it off. Normally I enjoy watching sports and would be glued to the screen. But I just don’t feel like it.

Relapse

Tuesday, August 3

Number of new cases in Tokyo: 3,709

As my condition stabilizes, the nurses help me make phone calls to my parents, my in-laws and my boss. Everyone sounds surprised to hear from me and I am happy to offer them some reassurance that I am going to be ok.

I am moved to a general ward. Nasal high flow therapy is being used to help my breathing. Oxygenated air is being delivered through tubes inserted into my nose. The sound it makes is like a strong, howling wind. I am able to open my mouth, so I can talk. I feel like I am ready to work on getting well enough to be discharged from hospital.

But the coronavirus won’t be subdued. A young doctor tells me, "Your oxygen levels aren’t getting better as we’d hoped," and once again, I am faced with the prospect of ventilation. The doctor’s phone rings and it is his supervisor on the line. I hear my condition being discussed and it seems they want to avoid a second ventilation because it places such a burden on the body.

The leader of the hospital’s coronavirus team comes to see me. "We thought your pneumonia would keep on improving, but there are signs of a relapse," he says. "We still have a lot of approaches to treat you and we’ll try to work out what’s best. Let’s overcome this together." I reach for his hand and he reciprocates with a handshake. Even though he is wearing gloves, I grab his hand tightly, grateful for the human touch.

Struggling with hallucinations

I am returned to the ICU and for the next three days am on tenterhooks, constantly worrying that I will be put back on the ventilator. The nights are especially tortuous and I’m starting to see things. The hallucinations include thick curtains dropping around me, and overlapping moons. Every time I try to sleep, I see kaleidoscopic patterns and get the sense that people are surrounding and moving around me. The coronavirus is taunting me. I exhale deeply to try and blow away an invisible enemy. I am scared to go to sleep because I’m worried I may never wake up.

My fever is high. I ask for two ice packs, and rest with one under my head and another tucked into my right armpit.

Nightmares

Wednesday, August 4

Number of new cases in Tokyo: 4,166

I am in a single room in the ICU. Above my head is a monitor that shows blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen level. The blood pressure monitor automatically takes a measurement once an hour. I have an IV drip for high-calorie infusion and there’s a tube inserted in my arm to take blood samples.

There’s also a device for the nasal high flow therapy, and nurses keep coming and going to adjust the flow of oxygen and to change my position on the bed. They always look busy.

If my condition worsens, I might require the use of a ventilator again. What kind of risk would that pose? I remember the doctors wanting to avoid its second use. As I try to sleep, once again I imagine crowds of people moving around. I tell myself it’s not real and stop myself from pressing the nurse call button.

As the night shift nurse comes into the room, I ask her if I am losing my mind. She offers some calm reassurance. "Judging by your responses, you are all right," she says. "Even if you see weird things during the night, try to accept it as part of the experience during your treatment, and be strong."

The nurses are there for me 24 hours a day. They are not only providing care directly related to my treatment, but will occasionally stay to talk. Although they face an enormous workload – plus the risk of becoming infected themselves – they are bright and lively. I am deeply impressed by their skills and attitude.

Thursday, August 5

Number of new cases in Tokyo: 5,042

My blood oxygen saturation level is back up to about 95. I am spared from a second ventilation and am now out of danger. "Don't you come back," smiles a nurse as I leave the ICU for a second time.

A three-week rehabilitation program follows before I am finally able to leave hospital. The doctor who discharges me has some words of warning: "Be careful of the virus, since you can be infected again. In addition, be aware that the same kind of treatment that you had may no longer be available. Medical resources are running out. Even if an ICU bed is available, we are lacking the medicine needed to operate the ventilators."