In Bangkok’s hospitals, intensive care units approached 90 percent capacity in late August. On one day in July, they were fully occupied. Health experts said there could soon be a shortage of key equipment, including ventilators, as the number of severe cases spikes.

Nearly 20 percent of Bangkok's residents live in densely populated slums, where it is harder both for authorities to enforce lockdowns and for people to comply with these measures at all. And to make matters worse, access to healthcare is limited. As a result, the COVID-19 fatality rate in these low-income areas is higher than elsewhere in the Thai capital.

One woman, whose mother was infected with the coronavirus, said she tried to call for an ambulance, but was told to wait until the symptoms were more severe. Unsatisfied, she contacted Zendai, a new organization that helps low-income people access PCR tests and finds them a hospital bed if need be. Its staff took her mother straight to hospital.

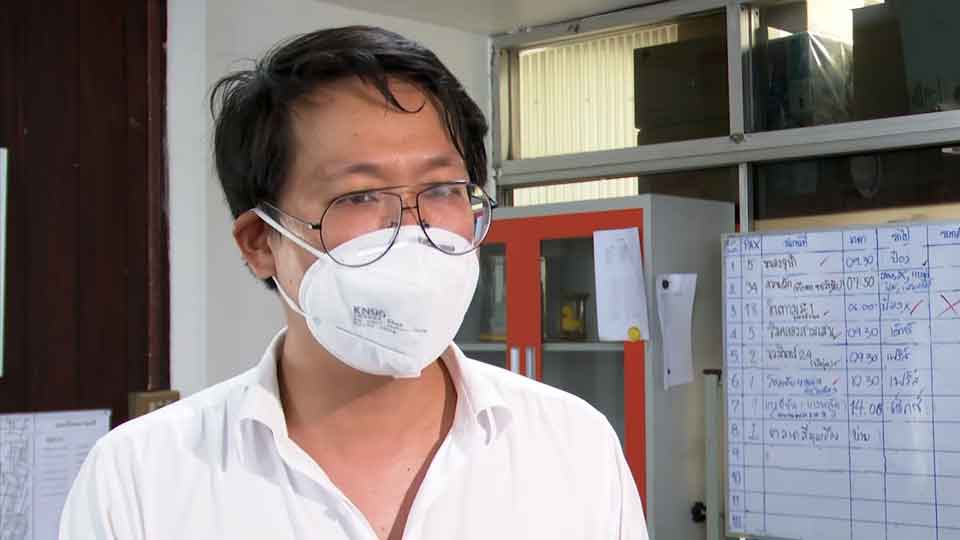

Zendai was founded in April by 33-year-old lawyer Chris Potrananda. The organization takes its name from the Thai word for "thread." Its 150-strong team of volunteers includes doctors, retired civil servants and ordinary citizens. Every day, it sends teams to low-income areas and transports people with symptoms or a high-risk of infection to a PCR testing site. Most days, the staff work late into the night trying to find hospital beds for as many infected people as possible.

Potrananda wants to expand Zendai's activities to cover all of Bangkok's disadvantaged areas. "There is a clear difference in access to healthcare. If you have money or private insurance, you can walk into any hospital, and you won't be rejected," he says. "But I believe if everybody helps, we'll be able to get through this crisis."

"Up For Thai" is another organization working to help low-income people in Bangkok. The volunteer group, founded by local celebrities, distributes lunches and survival kits to slums and factories with high infection rates. In early August, the group opened a 145-bed community isolation centre for severe cases to reduce the burden on hospitals.

Slow vaccination rollout

The growing infection rate and death toll is stoking anger over the government’s handling of the pandemic, particularly with regard to its slow vaccination rollout. Only 15 percent of the country’s population is fully vaccinated at the beginning of September. Earlier this year, most people received China’s Sinovac vaccine, but a domestic company is now producing AstraZeneca shots under license and the government is trying to procure more vaccines from overseas. As part of that policy, it has joined the COVAX Facility, an international framework for fair vaccine distribution.

For many people this amounts to too little, too late, and they are holding demonstrations calling for the Prime Minister's resignation on an almost daily basis, despite the risks of infection.

Some of those protests have turned violent, with police officers using tear gas and rubber bullets, and demonstrators setting fire to a police station.

The stricter anti-virus measures appear to be doing little to placate people infuriated by the pace of the vaccine program. As one protestor put it: "The government should show their sincerity by trying to import vaccines to help the people, and to rebuild the country's economy."