My reporting starts with a call I got from one of my sources. His son had been hospitalized for over a year with pediatric cancer.

He told me that a documentary filmmaker was coming to his son's hospital in Tokyo, and asked me whether I'd be interested in reporting on it.

I had never heard of the filmmaker before. But I watched her documentary, and thought it would make an interesting story.

Amazing strength of children

It's called "Everyday Heroes" and tells the story of five French children who suffer from life-threatening illnesses. The movie isn't a tear-jerker; it shows the kids as they are. For example, one girl talks about having pulmonary hypertension, and having to carry pumps in her backpack wherever she goes. She's candid; she doesn't hold back about her struggle.

There are other moments that show the kids sobbing, but mostly it shows them having fun, playing with friends.

The film shows the kids' strength, but it doesn't make them out to be trying to be tough. I think the message is that kids are born with the strength and will to enjoy every moment of life, even if they suffer from serious illnesses.

Julliand is driven by the death of her children

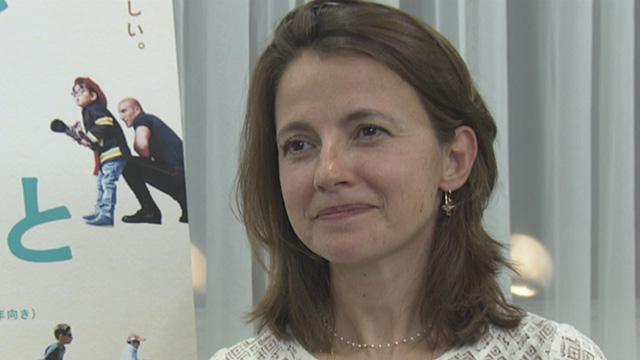

I met with the director, Anne-Dauphine Julliand, at the hospital. She was in Japan to promote the movie's release.

Julliand lost two young children of her own to serious illnesses; that was why she wanted to make the film. While promoting the movie, she met with Japanese children and doctors. She wanted to talk to people who were going through something similar to what she had experienced.

Before visiting the children's ward, Julliand went to a short stay unit, where seriously ill children stay and receive care.

Most of the children here are connected to tubes. Some are in the terminal phase of the diseases.

The facility alleviates the parents' heavy burden of continuously looking after their kids. The staff works to create an environment where the children can be who they are, and play as much as possible.

Julliand met a 2 year-old boy who takes nutrition through tubes. A staff member told her that the boy likes to bowl, and that once he starts, he never stops. Julliand told me this is an example of the strength shown by these children. When an adult goes through severe treatment, it is often difficult for them to find enjoyment elsewhere.

Julliand told the staff that she admires them for treating the children as if they didn't have serious illnesses. She says that in hospitals in France, she rarely sees facilities like this.

Toddler battling cancer

Julliand then went to the children's ward where she met Ayame, a 2 year-old girl fighting pediatric cancer.

She was with her mom, playing with blocks. As Julliand spoke to her, Ayame seemed to be trying to make sense of what was going on. She was looking into Julliand's eyes, sometimes glancing over at us, too.

Both Ayame and her mom were wearing masks. They wear them to block infections. The mom said it prevents her from showing Ayame how she feels, but that her daughter has learned to read her expressions just by looking into her eyes. Film sparks discussion

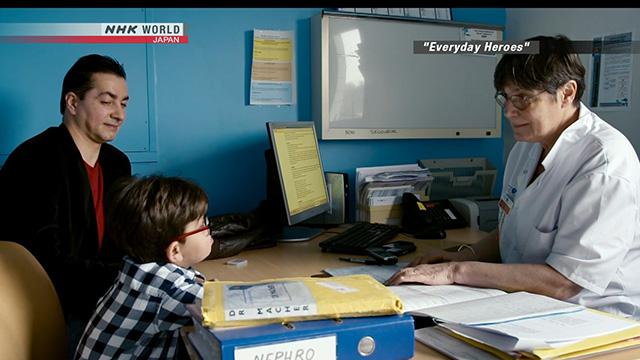

Julliand later attended a roundtable discussion with Japanese pediatricians. One of them brought up a scene in the movie that particularly struck him. It showed a conversation between a doctor and a boy. The doctor tells the boy the name of the disease he has been diagnosed with.

The doctor tells him how serious it is, what needs to be done to beat it, as well as the associated risks.

The pediatrician told Julliand that in Japan, doctors tend to downplay the seriousness of diseases, leaving things vague to put children at ease. He said that he sometimes tells kids they are simply infected by some kind of germ.

Julliand responded by saying adults need to trust the kids. She said they are capable of accepting reality, that they are more mature than adults think.

She recounted her own experience of talking to her kids. She said that when she told them of their diseases, they both cried. They were 2 and 4 years old. But she said soon after, they were playing again. She stressed to the doctors not to turn their backs on the children.

Teen survivors share raw emotions with me

I used to make half hour-long documentaries on pediatric cancer, and I learned then that children can pick up on what adults are holding back.

The survivors I met told me that when they were in hospital, they would wake up in the morning and see nurses changing sheets and cleaning up nearby beds. They said they could tell that one of their roommates had died, even though the nurses wouldn't say anything. They didn't ask the nurses about it because they knew they were holding back.

They told me that the next thing that came to their minds was, 'Am I going to be next?'

They experienced this when they were still in their early teens.

I also think not telling children the truth has adverse effects on the kids after they get well. Through my reporting, I've met a lot of survivors who find it hard to tell people that they had pediatric cancer. They think it puts them at a disadvantage if they confess to an employer or a significant other.

Some doctors cite adults' reluctance to be frank to their children as one factor that leads the kids to believe they shouldn't talk about their diseases when they grow up. Julliand told me she doesn't blame Japanese doctors because she thinks it's a mindset held by many adults in general. When they avoid telling children the truth, they do it for themselves, not the kids. They want to avoid the uncomfortable moment of telling them the truth.

I meet another "hero"

While I was filming Julliand's visit to the hospital, I ran into a former colleague. He used to host a show at NHK.

He had always been interested in how to improve social welfare services. He made several documentaries highlighting the issue.

Eventually, he quit to become a care manager. Leaving a career at a major TV network, and jumping into the welfare world, known for the hard work and long hours, must have been a tough decision.

But as I watched him work, it was obvious how much he enjoys it. He feels great doing what he's doing.

It convinced me that people with a passion for welfare are the ones out there supporting these children. But at the same time, I felt that they shouldn't be the only ones doing the hard work.

Society as a whole has to shoulder the burden. I learned through this reporting that we have to trust the children and bring them on board in the fight against these diseases.

What can I do?

I think everyone can do something to help the children. If you have time, you can join a volunteer group that cares for kids with serious illnesses. Or, if you have money, you can donate.

Being a journalist, I want to listen to the voices of these children, their parents, their doctors and caregivers. I want their voices to be heard widely, so people can at least be aware of the suffering they go through, and the issues that need to be addressed.

Through my work, I hope to search for what needs to be done to make the children's fight against life-threatening illnesses a little easier.