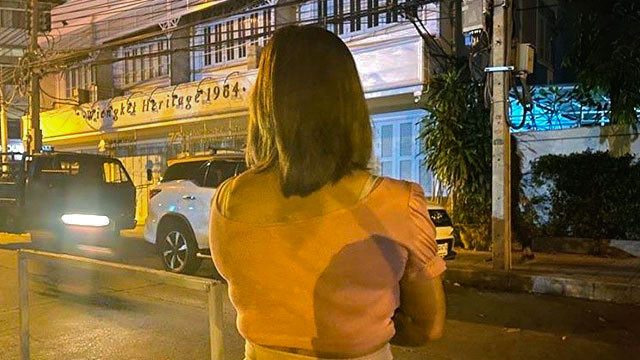

Aueng is from a rural farming region in the country’s northeast. Her 9-year-old son still lives there with her parents. She spoke to NHK on the condition of anonymity.

“I don't want anybody, not my parents, not my son, to know what I am doing,” she said. “But nothing is a secret forever. Part of me thinks they will find out eventually.”

Before the pandemic, Aueng earned about 730 dollars a month, most of which she sent back home. She also bought gifts for her son, and says that watching him play during their video calls is her greatest source of joy.

Prostitution is technically illegal in Thailand. But according to SWING, an organization that protects the rights of sex workers in the country, Aueng’s story is no exception. Women from rural areas move to major cities like Bangkok in search of employment. Due to lack of opportunities or misfortune, many end up working on the street.

But the coronavirus pandemic has meant that sex work is no longer a reliable source of income. The industry has been hit hard by the lack of foreign tourism, traditionally a major customer base. SWING surveyed 941 sex workers in January: 75 percent of respondents said they could barely afford a single meal a day; 45 percent said they did not have a place to live.

The Thai government has provided subsidies to those who have lost income due to the pandemic. But in many cases, sex workers are not eligible. Surang Janyam, the director of SWING, says the government must expand the qualifying parameters for assistance.

“They get no help because their work is considered illegal,” Surang says. “But they have to work and we should recognize what they do as an occupation. The crisis is affecting them the same as everyone else, and they should be able to receive assistance, like everyone else.”

Aueng has since found a new job at a restaurant and given up the sex work.

“Doing this once in my life was more than enough,” she says. “The only good that came of it was that I earned some money. But I don’t want to hurt myself. My dream is to live with my son again. That's all I want.”