“Chinese projects will be negatively impacted by the coup.”

Ebara Miki: How do you think this coup will affect Chinese interests in Myanmar?

Yun Sun: I don't think we have seen the end of this coup yet. We don't yet know how it’s going to end, whether there is going to be violence, a clash between the people and the military. If we’re hoping for the best-case scenario, maybe there will be a political deal between the people and the military. To judge how this coup is going to affect China's national interest is a little bit premature.

But based on what has happened in the past 24 days, the ramifications or the impact on China is manifested in terms of the hostile public opinion that we are seeing out of Myanmar. Many Burmese people believe that China is behind the coup and China has been supporting the military. We are seeing souring public opinion in Myanmar against China. That's number one.

Number two is that the international community is also asking a lot of questions and putting pressure on China to do more about the situation, to the extent that China agreed to a UN Security Council press statement [expressing “deep concern” over the military takeover and calling for the immediate release of Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint], and to the extent that the Chinese ambassador to Myanmar had to come out and clarify that China does not support the coup. I think the international and diplomatic pressure is the second largest impact with regard to China.

A third effect is a little bit further down the road, maybe in six to 12 months, which is what is going to happen to Chinese projects in the country. On the ground, we know that, under the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, Beijing has planned a series of economic cooperation projects with the NLD government. This is not to say that the military will not pursue the same projects. In fact, I think the military will be more than eager to work with China on these projects because now, with pending international isolation and sanctions, their choices are going to be limited. But to what extent will China be willing to carry the uncertainty in terms of the investment environment and against international pressure, which is going to be a huge, unpredictable factor? I do not think that the Chinese economic projects are going to progress as a result of the coup. Actually, I think they are going to be negatively impacted.

“Myanmar is important to China because of its location.”

Ebara Miki: What is Myanmar’s strategic importance to China?

Yun Sun: That's a good question. There are different answers but in my analysis, Myanmar is important for China not because of what the country itself can deliver. When we look at the economic cooperation between the two countries, yes, Myanmar has natural resources, some hydropower resources, mineral resources and energy, oil and especially natural gas exploration off the coast. But these are all really limited. And if we look at market size, the Burmese population is somewhere around 52 million people, sizable for Southeast Asia, but not the most significant in the bigger picture.

Myanmar is important for China because of its location, because of what Myanmar can connect China to. We know that Myanmar sits on a critical location between South Asia and Southeast Asia. It’s also one of two countries to offer China direct access to the Indian Ocean. The other is Pakistan. By comparison, the security risks in Myanmar are relatively low. So China looks at Myanmar as primarily a connective hub, a transportation network to not only South Asia, but also Southeast Asia as well as the Indian Ocean, which is why key Chinese projects in Myanmar, either the oil and gas pipeline or the Kyaukphyu seaport, all represent ways to connect China with the rest of the world.

Ebara Miki: Beijing has described the bilateral relationship as the “Sino-Myanmar Community of Common Destiny” . What does that mean?

Yun Sun: That is a political term that carries significance. I actually think that even without a “Community of Common Destiny”, China was due to pursue a very close relationship with Myanmar because of its strategic location. But for China, what happened in Myanmar between 2011 to 2015-16 represents a major shift in bilateral relations. It was a period when people believed that China lost Myanmar to the West because of democratic reform, and also because of the suspension of the Chinese Myitsone dam project. It was a period where China's influence in Myanmar seemed to wane.

I think in China’s mind, it has always been a priority to regain that influence, to regain the favorability of the Burmese government, and show that China will not lose in Southeast Asia vis-à-vis the West, especially the United States.

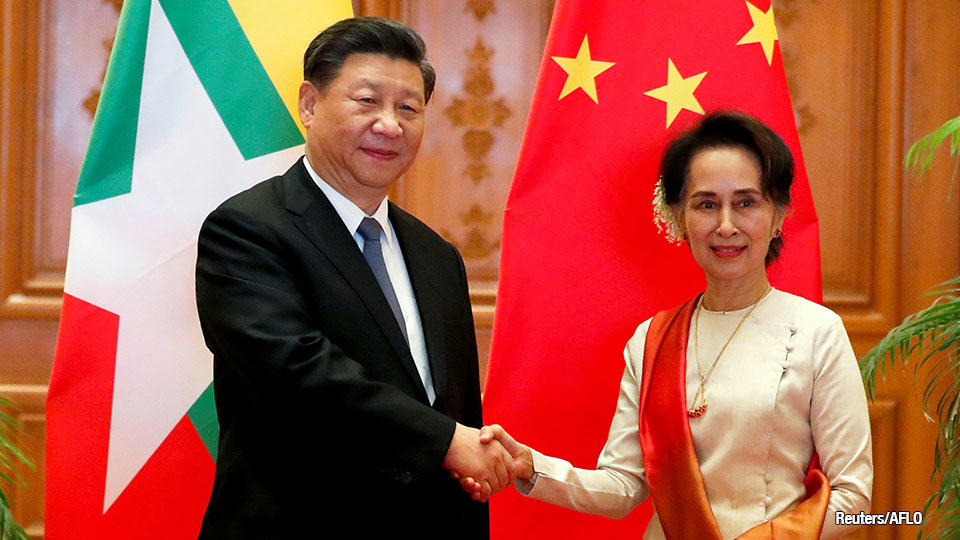

I think another factor about this “Community of Common Destiny” is the Rohingya crisis. We all know that because of the Rohingya crisis, the refugee issue, the NLD government and Aung San Suu Kyi faced increasing international sanctions and criticism. During this period, China stood firmly behind her, supporting the Burmese people and government, including the military. It was an opportunity for China to rebuild its influence and to regain the trust of the Burmese people. So, I think when China talks about the “Community of Common Destiny,” there are multiple layers of political significance. And the strategic location of Myanmar is only one of these considerations.

“China prefers Myanmar as a normal and stable country.”

Ebara Miki: So what you’re saying is that it doesn't really matter to China whether the leader is Aung San Suu Kyi or the military commander-in-chief?

Yun Sun: No, it matters significantly. If China had the choice, it would prefer for Myanmar to be a relatively normal and stable country. A Myanmar under the rule of the military is neither normal nor stable. The situation in the country has a huge effect on what projects China can pursue. There is actually a huge difference between the NLD government and the military for China and what it is trying to do in Myanmar.

But the problem is this is no longer China’s choice. Beijing may not like the coup, but it cannot do anything to reverse or stop it. If China doesn't have a choice, then China will have to work with whoever is in power. And that's exactly what we're seeing today.

Ebara Miki: What can China do now to affect the situation?

Yun Sun: There are things that not only China, but also Japan or India or the international community at large can do. People are looking at the UN and ASEAN to see what they do about the situation.

But the first issue is: Do countries share a consensus on what needs to happen in Myanmar? And when I look at the countries’ preferences and what they're trying to push for, I see a very wide spectrum of options on the table. For example, is it our goal to completely reverse the coup, to make things go back to the status quo? Or are we aiming for a new status quo, a caretaker government and a political deal between the NLD and the military? For us to move forward, the first question should be not what China can do, but what is our goal overall.