The government unveiled its proposed changes earlier this month. The revisions would allow certain foreign nationals who have been subject to deportation orders to stay with family members or supporters. They are currently held in government detention centers. The measure is also proposing an alternative system to detention that limits the number of people at these centers by appointing individuals and support groups to house detainees and help them maintain a connection to society.

Last September, the UN Human Rights Council specified that Japan's long-term detention policy—which sees some people detained for years—violates the International Covenants on Human Rights.

The number of detainees has dropped by more than half as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, with authorities releasing people to try to limit the risk of an outbreak. But according to the Immigration Bureau, there were still 527 people in detention as of June 2020, including 232 who had been held for more than six months and 47 who had been held for more than three years.

Arikawa Kenji, director of the Arrupe Refugee Center, an independently run shelter in Kanagawa Prefecture, says using the proposed alternative could help to avoid unnecessary detentions. But he points out that it leaves many questions unanswered, such as the legal responsibility of the shelters if a detainee runs away, or who shoulders the burden of medical fees as most foreign detainees are ineligible for welfare.

The revision also shortens the re-entry ban from five years to just one if they return home at their own expense. The idea is to encourage detainees to leave the country of their own volition, but the law gives no assurance that people will be allowed to re-enter Japan at the end of the ban.

The revision also adds controversial provisions to the law. The authority can levy criminal penalties on people who refuse deportation orders. In addition, it proposes deporting asylum seekers who have applied for refugee status three or more times, a measure which some believe violates the principle of non-refoulement, enshrined in international human rights law, that those applying for refugee status cannot be returned to a country in which they could be subject to inhumane treatment.

"The revision makes the law even worse," says Ohashi Takeshi, an attorney who has handled immigration cases for over 20 years. He adds that the overall design to the system, which is to force people back to their countries, has not changed.

Solidarity Network with Migrants Japan, a network of over one hundred support organizations, says the draft falls short because it does not abolish the principle to detain people who refuse deportation. It also adds that the proposal does not address the underlying problem of Japan's immigration policy which is the fact that the country accepts fewer than one percent of asylum seekers. This is the lowest among developed countries.

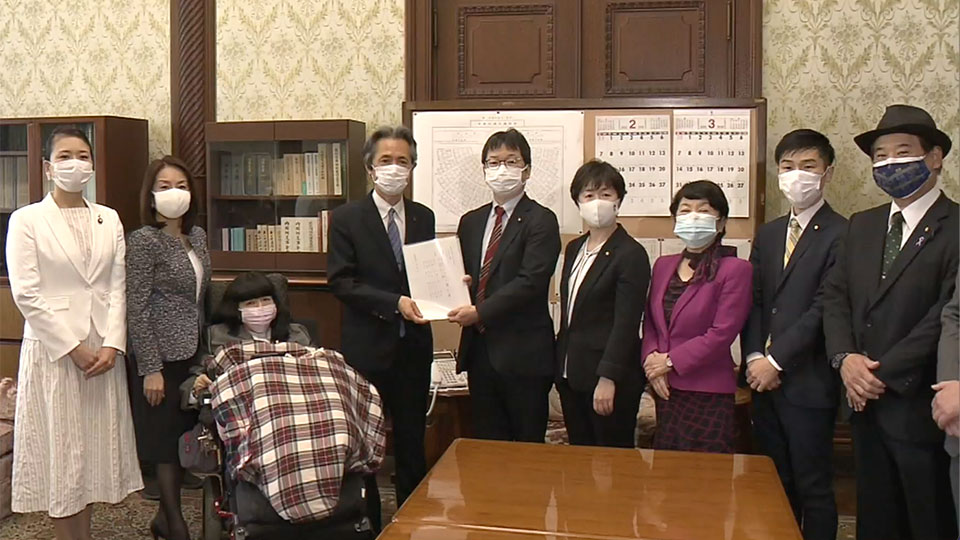

The opposition parties have submitted their own revision, saying the government draft doesn't adequately protect the rights of foreign nationals. Their proposal would make a court order necessary for detention and limit its extension to six months at most. It also recommends setting up an independent expert committee to examine refugee applications.

Ishibashi Michiro, a member of the Constitutional Democratic party, says Japan must revise its policies in accordance with the standards set by the UN and the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, which it signed 40 years ago.

"We hope our proposal influences the debate to protect the rights of foreigners and changes a system to something more appropriate for Japan as a member of the international community."

Both the government draft and the opposition proposal are expected to be on the agenda in the current Diet session.