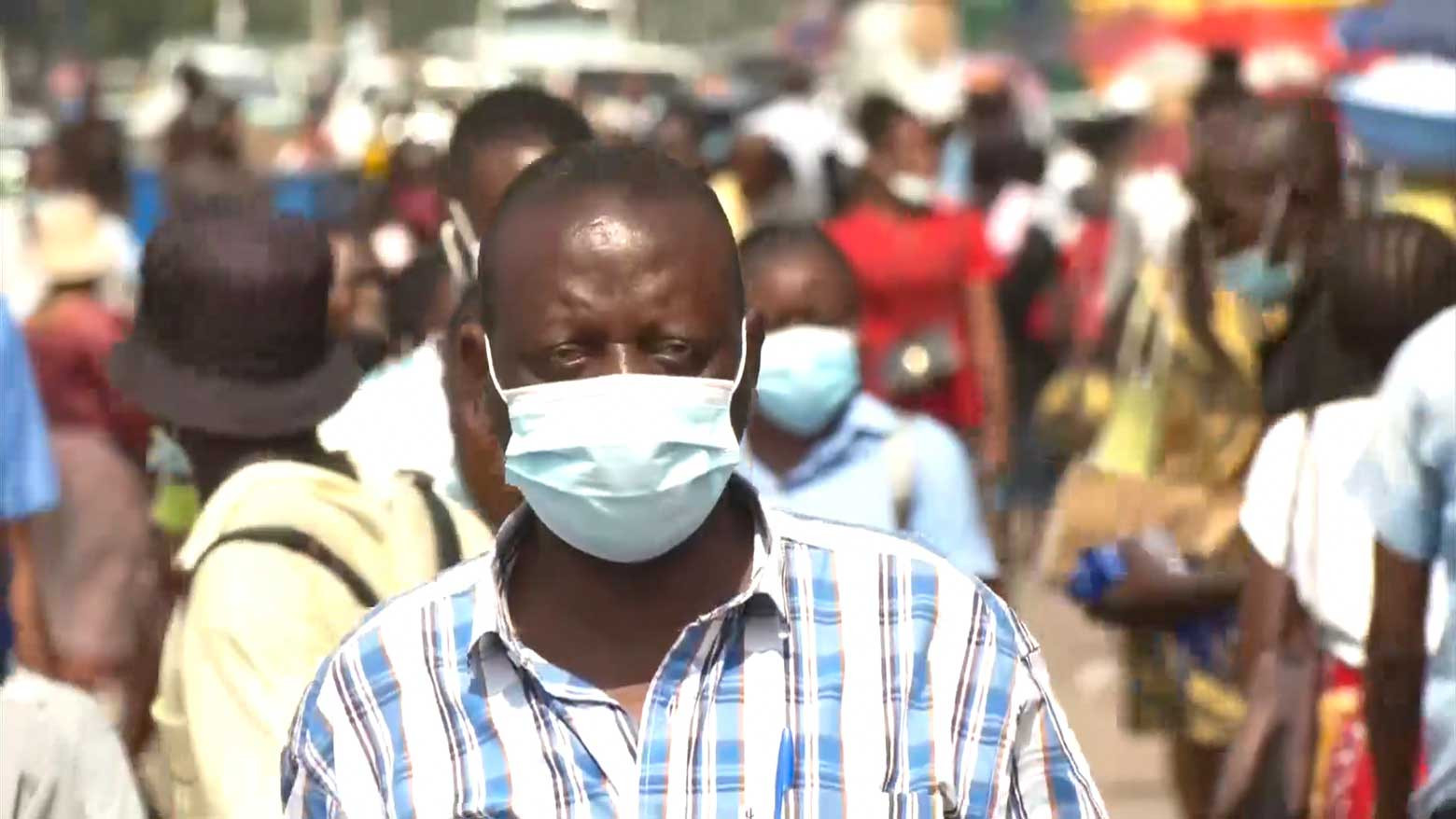

Grim prospects for Africa

Cases in the Republic of the Congo are hovering around the 8,000 mark. PCR test sites are packed in the capital, Brazzaville. Quite a few people say they want to get vaccinated, but the central African nation is finding it hard to act. Reasons include a lack of funding.

Medical personnel are increasingly worried. Michael Kombo, who works at a testing site, says people on the frontlines must be inoculated first. "It's always important to get vaccinated. We are in contact with patients all the time. It's not easy. There are some who accidentally spit on us when we do the tests."

Meanwhile, an analysis by the international organizations including Oxfam shows that some countries have secured a lot more vaccines than its population. It says Canada has purchased enough to cover its population five times over.

In contrast, it shows that only one in ten people will be able to get vaccinated this year in 67 nations, mainly in developing economies unless urgent action is taken.

"If we look at the picture today, it's quite starkly inequitable," says Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, the World Health Organization's regional director for Africa. "It is a situation that is highly regrettable, and not in the spirit of global solidarity," she continues. "There's no country that can shut itself off, survive on its own and then find that it's okay."

Moeti points out that the pandemic can't be stopped if only developed nations press ahead with their vaccination campaigns.

One refrigerator

India's vaccine rollout began in January. The government aims to have 300 million people, including medical personnel and those aged 50 or older, inoculated by summer. Millions have already had theirs – but the situation is far different in some remote parts of the country.

Prabir Chatterjee is a doctor at a hospital in a rural part of West Bengal. He says getting enough doses is one thing, but being able to actually administer them is quite another. Vaccines must be transported from a medical hub more than 20 kilometers away. They need to be stored in a freezer, but the hospital has only one home-use refrigerator. What's more, electricity supplies are unstable.

"You can keep medicine in it, but it is not the best thing for vaccines," the doctor says.

The hospital doesn't have enough doctors, either. Only two are on hand to handle about 13,000 residents. Vaccinating everybody is likely to disrupt the facility's regular services.

The doctor says 20 doctors must be assigned to the region before anything else. Otherwise, he warns it will probably take three years for 70 percent of the locals to be vaccinated.

The Indian government is providing free vaccinations for 30 million people including medical staff and police officers. Details are yet to be revealed for other citizens. Some people fear they may have to pay.

Tuhin Dutta, who runs a metal processing business in West Bengal, was unable to work for six months last year due to the pandemic. He used to earn about 280 dollars a month, but that suddenly dropped to zero. If vaccinations aren't free, getting his entire family inoculated will be difficult. He's concerned that rural areas may get left behind.

"Not to my knowledge has someone been vaccinated in our area," he says. "There is a high possibility that more vaccines will be provided to cities, where there are more people."

Ensuring fair distribution

The COVAX Facility, an international project works to ensure the fair distribution of vaccines worldwide, including in developing nations. The WHO is one of founding entities, and 190 economies are currently taking part, but supplies of coronavirus vaccines are yet to begin.

Dr. Seth Berkley, the CEO of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, is one of the project's leaders. He's urging countries to cooperate, as opposed to what's happening now.

"What we've also known is that many wealthy countries, because you don't know at the beginning which vaccines are going to work, have bought many more than is needed to cover their populations," he says. "So in that case, we're also working with countries to hopefully be willing to donate some of those doses or give up their manufacturing spots so we can have more equitable distribution."

COVAX aims to start rolling out vaccines this month, and supply its first 150 million doses by the end of March.

Currently, global coronavirus cases exceed 100 million. More than 2.2 million people have died. Dr. Berkley says the pandemic cannot be stopped if vaccines aren't available to everybody in every nation.

"If you have large parts of the world that do not have vaccines, and therefore the virus is circulating without any stopping at all, then that puts everybody at risk."