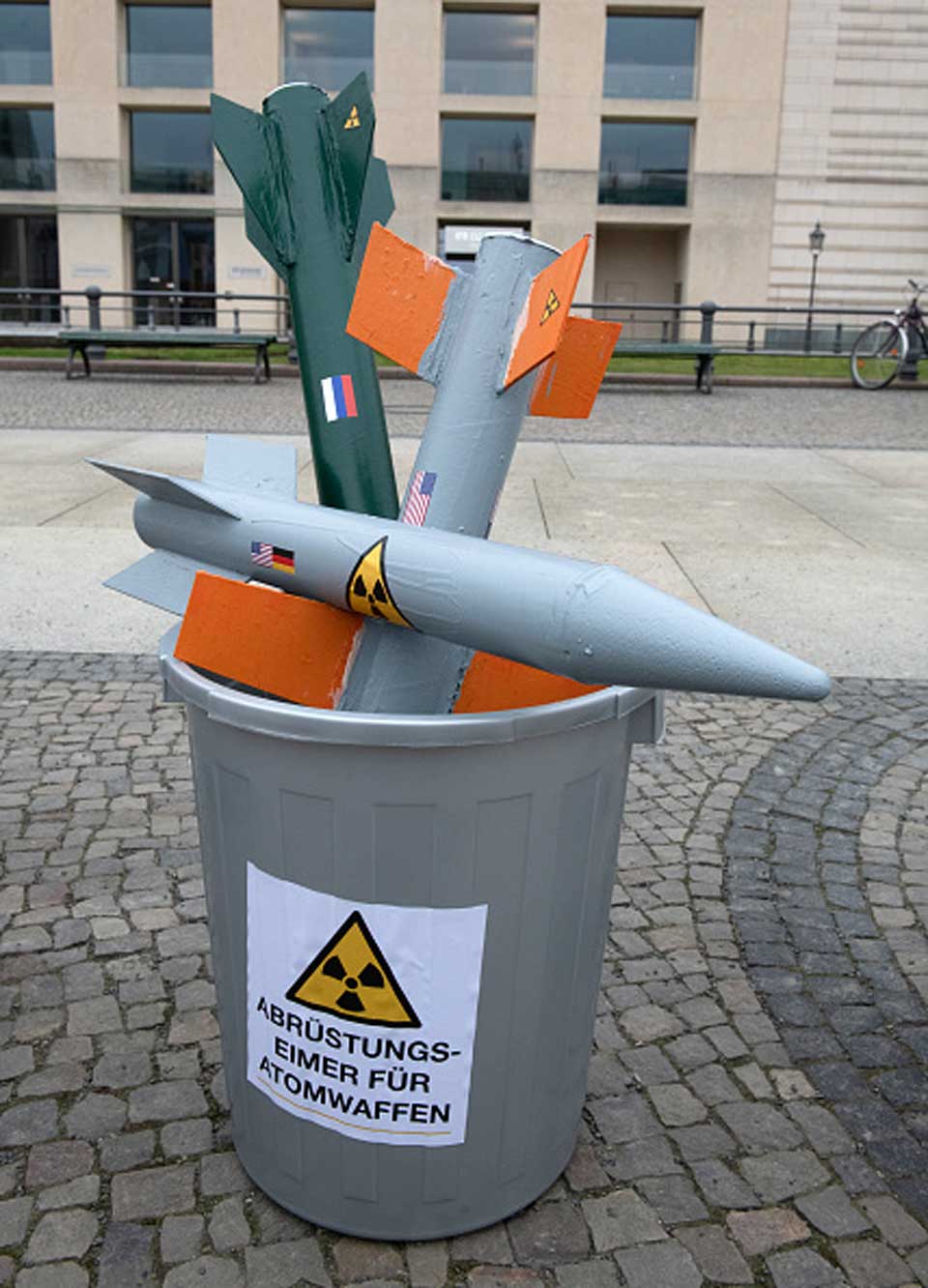

However, enthusiasm is dampened by the fact that not a single nuclear power has signed on to the treaty. Even NATO members and Japan have withheld their support, saying that TPNW doesn’t do enough to address global security concerns. Without the participation of so many countries, the prospect of meaningful nuclear arms reduction — not to mention elimination — remains a pipe dream.

As the world struggles to battle the coronavirus, the issue of nuclear arms has faded from our collective consciousness. Yet the fact remains that nuclear powers still hold 13,000 of the weapons in their arsenals. And they are not just an abstract danger.

In recent years, Russian President Vladimir Putin threatened to use nuclear weapons against Ukraine, and former US President Donald Trump mulled launching them against North Korea. These major powers, as well as China, are not reducing their arsenals; on the contrary, they’re updating and improving them.

The world continues to be ruled by the nuclear deterrence theory, which posits that no country would dare launch a first strike because a retaliatory attack would ensure its own destruction. Thankfully, nuclear weapons have not been used since the World War II. But there’s no guarantee that a current or future leader will never deploy them.

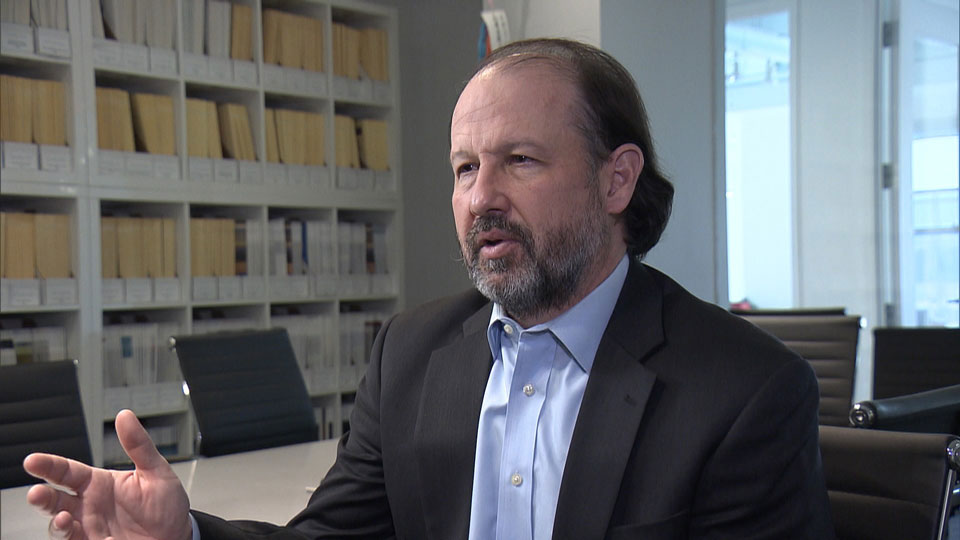

Does this mean the TPNW is meaningless? Not necessarily, says Daryl Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association, a prominent think tank in Washington, D.C. He believes two factors have the potential give the treaty some teeth.

“When the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty went into effect in 1970, there were very few participating nations, and until the 1980s, not even half of the UN member countries joined,” he says. “The TPNW differs from the NPT in that it was negotiated among more than 120 counties. As a result, I believe more than 100 nations will ratify the treaty in a short timeframe.”

Kimball points out that the treaty enjoys broad popular support.

“In discussions among NATO member countries, the majority of people advocate for the abolishment of nuclear arms. Most people argue that Spain can ratify the treaty… I think a turning point will come when NATO member countries that accept nuclear arms [within their borders], as well as those that don’t, ratify the treaty, making it universal.”

Kimball is referring to a decision last year by the Spanish Parliament to recognize the potential of the TPNW to free the world of nuclear arms. Belgium has also begun to regard the TPNW more positively.

Yet not a single NATO member is seriously considering participating in the agreement, and there are no prospects of any nuclear powers joining. This situation persists despite the encouragement of countries that support the treaty, as well as the advocacy of NGOs like the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons.

The goal, instead, is to universalize the opinion that nuclear arms are dangerous, as support for the treaty grows around the world. Advocates hope that this will pressure nuclear powers to pursue disarmament.

Kimball says he’s hopeful that the incoming US administration of President Joe Biden will take a more proactive stance.

“President Biden has a deeper knowledge and experience with the threat and control of nuclear weapons than any other US president in history,” he says. “It is obvious that he will work toward nuclear disarmament and a nuclear-free world. The Biden administration will probably not support the treaty and has not made any pledge to sign it, but it is possible that it will declare that the TPNW will contribute to a shared vision of a nuclear-free world.”

What, exactly, is ahead for the treaty? Within one month of joining, member countries must report to the UN Secretary-General whether they are in possession of nuclear weapons. The UN Secretary-General has also invited signees to attend a meeting to discuss how the treaty will be implemented.

“[The UN] has a responsibility and role to play in addition to ratifying [the TPNW],” says Nakamitsu Izumi, the UN Under-Secretary-General responsible for arms reduction. “We are preparing to implement it properly.”

Nakamitsu says signees have already started discussing how and when to meet, and what their top priorities should be. The treaty permits non-signatory countries to participate as observers, and several have already indicated interest in attending. Nakamitsu believes these countries can play a key role in determining the treaty’s success or failure.

“There are voices in Japan that support its participation as an observer, and I truly hope this becomes a reality,” she says. “I think that Japan, as the world’s only nation attacked by nuclear weapons, should not pass up the opportunity to participate in the dialogue about the treaty.”

Nakamitsu also welcomes Japan based on its role as a mediator between countries that possess nuclear weapons, nations that fall under their umbrella, and non-nuclear states.

Unfortunately, members of organizations in countries that are enjoy the protection of nuclear powers fear the treaty will widen the gap between nuclear and non-nuclear states. They say that in the final stages of the ratification of the TPNW, there were several instances of nuclear powers working behind the scenes to pressure non-nuclear powers to not ratify the treaty.

Whether the treaty will advance, stall, or set back nuclear disarmament efforts depends largely on an NPT Review Conference that is scheduled for August at the UN. This is because the five nuclear powers charged with nuclear disarmament under the NPT are all signatory nations of that treaty.

When considering the path toward disarmament, therefore, the NPT and the TPNW must not stand in opposition; instead, they complement one other. This puts a large burden on the United States, a nuclear superpower, as well as the UN and Japan, which will liaise and mediate on both sides.