The Republic of Kiribati is located in the central Pacific Ocean about 4000 kilometers southwest of Hawaii. With the population of over 110,000 people, the country's main industries include fisheries and the production of copra, the meat from coconuts from which coconut oil is extracted.

In the 1950s through the early 60s, the United States and United Kingdom carried out a series of nuclear testing on Kiribati. It was part of a bigger project happening throughout the Pacific, where more than 300 nuclear tests were conducted over half a century.

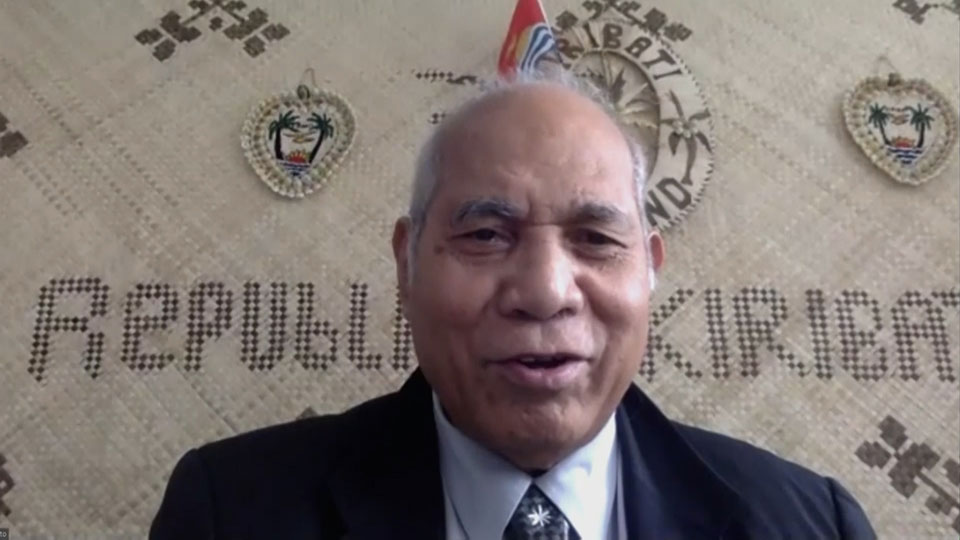

Teburoro Tito is the former president of Kiribati and the current UN Ambassador. Kiribati was the 28th country to ratify the accord, and Tito was one of the members behind the drive. "The moment has come when humanity has a big hope for the future. This is just a start," he said of the occasion.

Tito's interest to nuclear disarmament led Kiribati joining the UN in 1999. But it was a visit to Hiroshima -- the first city to be destroyed by an atomic bomb -- that had a lasting impact on Tito. He remembered visiting the peace museum and said he was shocked to learn what happened 76 years ago.

"We should never allow that to happen again. I don't want anyone to suffer like that. We must learn from the mistakes we make," Tito said.

Fifty-two states have ratified the treaty so far, surpassing the 50 necessary to come into force. However, the nuclear powers and nations such as Japan that fall under the US nuclear umbrella have not joined the treaty. In Pacific nations, the treaty also proved controversial for some.

In Kiribati, it is said that there are still dozens of victims affected by the nuclear testing, and hundreds of their descendants. Little is known about the victims though, and researchers across the world continue to investigate the effects.

The UN treaty requires state parties to assist victims and remediate the environmental affect from the use and testing of nuclear weapons. It also makes obligatory international cooperation and assistance. Tito hopes the treaty will help usher in a new era of support for Kiribati's victims and ensure no one else suffers.

"We will collectively work to convince nuclear states and Japan. We have to tell them that they have to join for the sake of their children and children's children. For the sake of humanity," Tito said.

While Kiribati may be just a ripple in the ocean, the country is hoping that making enough waves will steer the major nuclear powers and umbrella nations towards a nuclear-free future.