"Help me! Help me!” “This is too much!”

A video recorded last year by immigration officials shows a distressed detainee screaming for assistance as he is held down by several guards. According to the immigration bureau, the man was restrained because he had become emotionally unstable and broke the rules.

The man in the video is Deniz, from Turkey. He says he faces persecution in the country as a member of the Kurdish minority. Deniz arrived in Japan in 2007 and has repeatedly applied to be recognized as a refugee. Years later, he is still waiting. He has been married to a Japanese woman for nine years.

Years in detention “broke him”

Deniz has been ordered to leave Japan but he refuses, claiming he would not be safe back in Turkey. He spent a total of more than five years in detention. He says the hardest thing was not knowing if, or when, he would be released.

Under Japanese regulations, once someone is ordered to leave the country, they can be subject to detention until they agree. But international law prevents asylum seekers from being forcefully returned to their country. These laws have created a situation in which asylum seekers can be held indefinitely.

The detention period can have a harmful effect on physical and mental health. Deniz was diagnosed with depression, became dependent on medication, and made several suicide attempts. This March, he was granted a provisional release but has found it difficult to return to normal life. His wife says that when they talk about his situation, he gets despondent and wonders out loud if he is better off alive or dead. She believes the years in detention “broke him”.

United Nations levels criticism at Japan

Deniz’s lawyers reported his case to the UN. It was considered by the UN’s Human Rights Council that sent a brief to the Japanese government in September urging a review of long-term detention policy. Deniz wants the government to respond, and hopes to change something for those who remain inside immigration facilities. As of June this year, nearly a third of the detainees in the facilities had been held for more than a year.

The UN claims that Japan is threatening physical safety and freedom as laid out in the International Covenants of Human Rights. Its brief to the Japanese government points to the current system that allows people to be detained indefinitely without cause. It also criticizes the current rules for lacking judicial review – and violating international law – and urges Japan to put proper judicial process in place, and set a maximum period for detention.

The official position from the Immigration Bureau is that detentions are carried out appropriately under Japanese law. But with stricter entry controls being implemented in recent years, the extended periods faced by some asylum seekers are a growing concern for detainees as well as immigration officials.

“What’s the difference between me and other kids my age?”

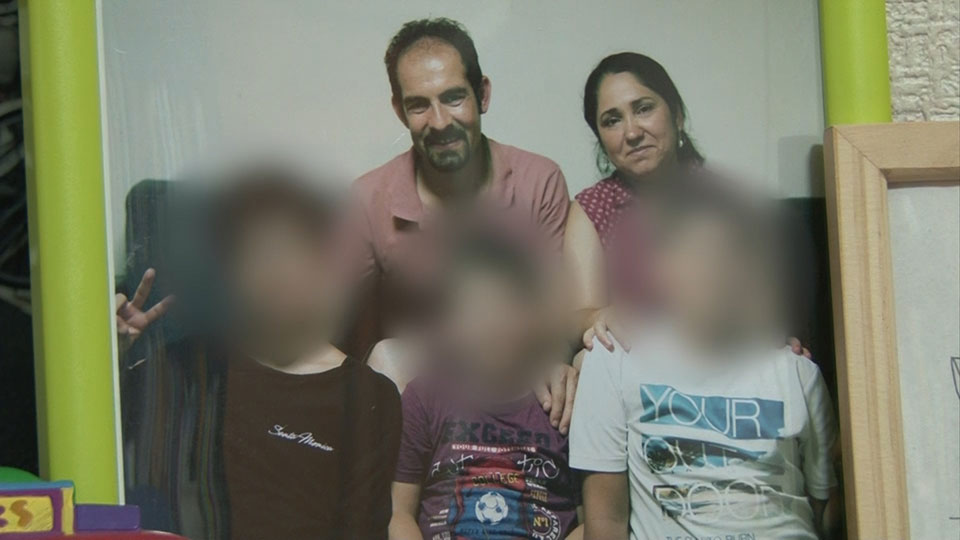

Some would-be refugees have children in Japan who also face uncertain futures. Mehmet, another Kurd, was detained for a total of 20 months. He has applied for refugee status four times over the past 16 years but is yet to be approved. His wife and son joined him in Japan and their family has grown to include two more children.

Mehmet’s eldest son, Mustafa*, is 16 years old. He was brought to Japan at the age of two and has attended local schools. He communicates in Japanese and barely speaks Turkish. He is now in high school and hopes to become a game programmer in Japan. But like the rest of his family, he is under an order to leave the country with a current immigration status of “provisional release.”

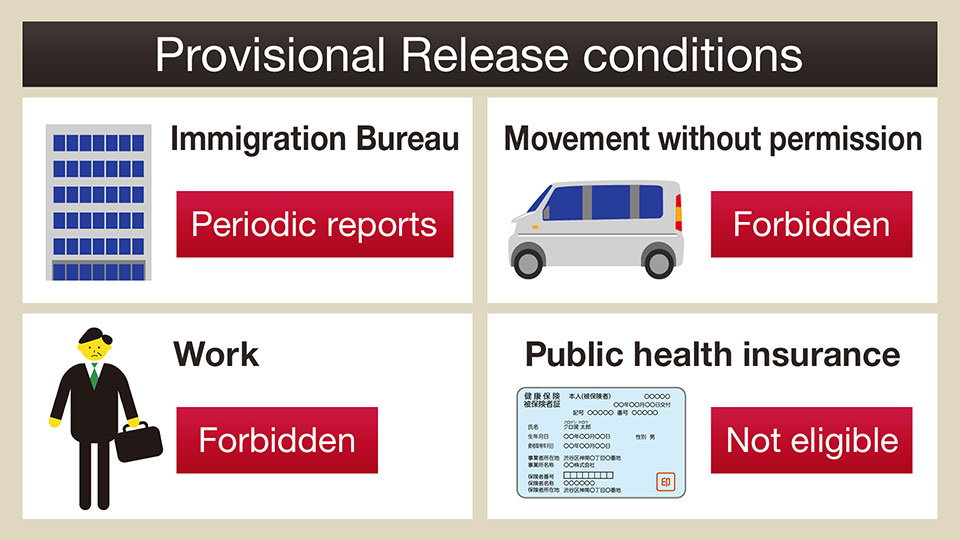

People with this status have to report periodically to immigration authorities. They are not permitted to work and are ineligible for public health insurance. Mustafa’s family has no way to earn a living and is dependent on financial help from relatives and support groups.

There are around 300 children in Japan like Mustafa. Minors do not face detention but Mustafa is worried about what will happen to him and his brothers when they reach adulthood. He sees the situation as unfair, asking, “What’s the difference between me and other kids my age?”

Special residence permits, a possible solution

Last year, Mehmet resorted to a last option, going to court to ask for special residence permits for himself, his wife, and his sons, hoping the court shows sympathy toward their situation. It’s an unlikely course of action as the number of successful applications has decreased by 90% since 2004. And some experts say the courts need to be more flexible.

Suzuki Eriko, a professor at Kokushikan University in Tokyo, says the situations of long-term illegal families alter considerably over time and that the government must take these changes - as well as those in immigration policy - into consideration when ruling on special residence permits. She believes that allowing residency status for long-term illegals is key to resolving the issue.

Japanese panel proposes harsher penalties

The death last year of a Nigerian detainee on hunger strike prompted Japan’s government to set up an expert panel to suggest a new approach. The panel’s proposals are the basis for discussions about a revision of the immigration control law that will take place possibly as soon as the next Diet session in 2021.

The recommendations include reconsideration of individual circumstances when setting the length of detention or deportation, and clarifications on special resident permit decisions. The panel also suggests alternative mechanisms to detention, but fails to address how people with provisional release status can sustain a living. There is also no mention of a maximum time limit for detentions.

Furthermore, the panel’s proposals take a tough approach that include possible criminal penalties for people who refuse orders to leave the country, and possible deportation for people who have made three or more applications for refugee status.

Many families like Mehmet’s who have children born in Japan are already beyond the three-application threshold, meaning they could face criminal charges and deportation. Such penalties could violate international law.

At the same time as authorities crack down on so-called illegal residents, Japan’s government has been enacting new policies to allow more foreigners to work in the country to offset the effects of a rapidly shrinking population on the labor force. Critics say the detentions and restraints on long-term residents who are already well integrated in their communities is not only a contradiction, but counter-productive to Japan’s economic future and its role in the international community.

(* name has been changed to protect identity.)