Yang Min’s only daughter contracted the virus at a hospital where she was admitted on January 16 for another illness. On February 6, she died from COVID-19. The mother, also infected, learned about her child’s fate after returning home.

Back then, rumors about the danger posed by the virus were only just starting to appear. Yang says she initially dismissed them as groundless – based on a state-run television report about a person who was questioned for spreading false information.

Now, she blames herself. “If I hadn’t been so trustful, my daughter wouldn’t have died. She was everything to me. I can no longer hear her voice, and it’s all because of my ignorance.”

Seeking answers and accountability, Yang started a sit-down protest outside a local government building. She was forcibly removed.

She began exchanging information on social media with other bereaved families, but many feared the authorities would come down on them hard. Like the protest, Wang’s online quest became a lost cause.

“For the authorities, life is eternally joyous. But for us, it’s terrible. Them and us – we’re in totally different worlds,” she says. “Officials should at least explain to the victims’ families who covered up the situation about the virus, and why. That way, the deceased can rest in peace and their relatives can maintain a mental balance.”

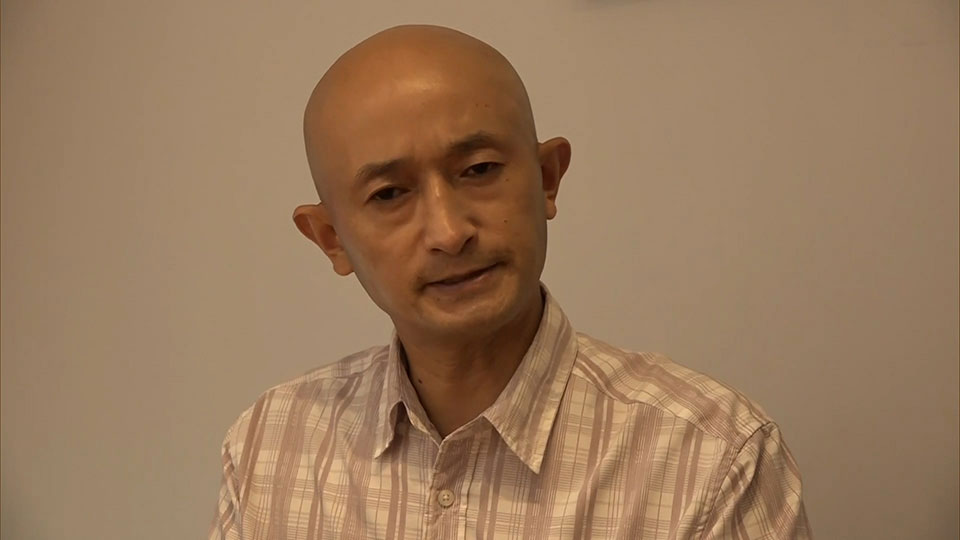

Wuhan native Zhang Hai had moved to the southern province of Guangdong due to his job. His 76-year-old father, who joined him, was taken to the hospital on January 15 after taking a fall. Zhang says his father was told he could receive surgery for his broken bones back in Wuhan. What’s more, the cost would be covered with public funds, in part because his father was a veteran soldier with a family register in the city.

The virus was believed to be spreading quickly in Wuhan at the time, yet Zhang still drove his father to the city. He’d taken heed of the local authorities, who insisted there was no need to be on alert because human-to-human infections had not been confirmed.

The surgery went well – with one fatal caveat. His father was diagnosed with the virus. By February 1, he was dead.

“I felt like I’d driven my father to his death,” Zhang says. “I regret what I did. If I’d known the situation in Wuhan was that grave, I’d have never taken him. I’m so angry at the authorities.”

Zhang decided to sue Wuhan. He wanted compensation and an apology, but with hardly any explanation at all, the court told him there would be no suit.

“If those responsible go unpunished, officials will try to cover up serious problems again. It’s us, the ordinary folk, who’ll suffer,” Zhang says. “I love my country, and the Communist Party. That’s why I’ve been pursuing accountability. The authorities can keep pressuring me. It won’t stop me from getting those involved in the coverup to take responsibility.”

The Chinese government says more than 50,000 people have contracted the virus in Wuhan. The death toll exceeds 3,800.