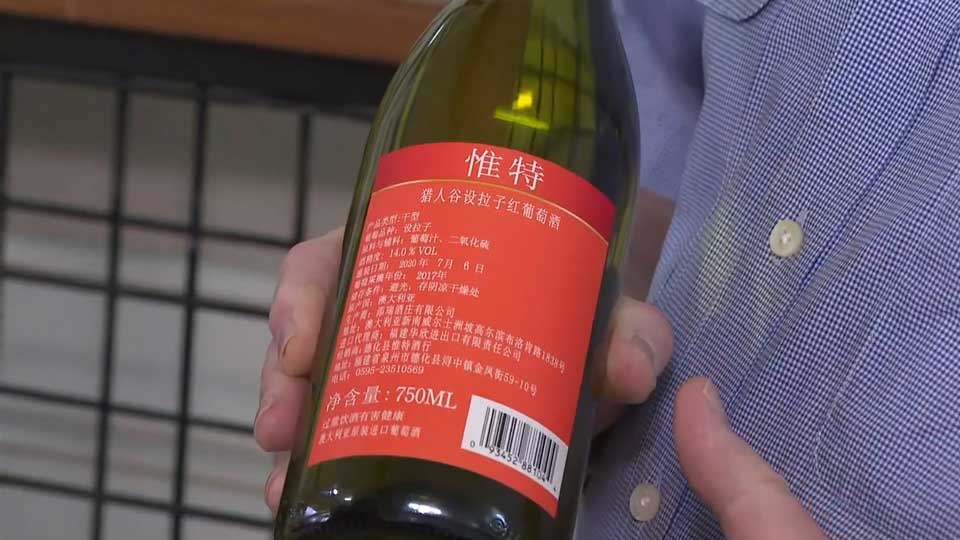

Bruce Tyrrell's family has been making wine in Australia's Hunter Valley for more than 160 years. His products are popular around the world, but his biggest foreign market by far is China.

"Almost 50% of [our output] is going to mainland China," he says. "But more importantly, it's continued to grow in value. Of all our export markets, it's the one with the highest average price per bottle."

But Tyrrell has been watching Australia's relationship with China unravel and says he is now rethinking his company's strategy.

In August, the Chinese government launched an investigation into whether Australian winemakers had "dumped" wine at low prices. Beijing says it may increase tariffs, pending the outcome of the investigation.

Years of weakening ties

The tariff threat is amongst a number of recent actions stemming from a spat that goes back to 2016, when Sam Dastyari, an Australian politician with links to Chinese donors, gave a speech backing China's claims to disputed territories, contradicting his party's stance. The incident raised concerns about Chinese meddling in Australia's politics and prompted Canberra to introduce legislation banning foreign interference in domestic affairs. But that law has been less than successful. In November of 2019, media reports claimed that a Chinese-Australian man, Bo Zhao, had been approached by Chinese spies to run for federal parliament. He reported the overture to Australia's security services and was later found dead under mysterious circumstances.

Australia has taken a more assertive approach toward its biggest trading partner this year. Prime Minister Scott Morrison called for an investigation into the origins of the coronavirus, calling for China's cooperation and transparency.

Three months later, Australian foreign minister Marise Payne and defense minister Linda Reynolds visited the United States for talks with their counterparts. The two countries declared they would work together to confront China and "reassert the rule of law" in the South China Sea.

China responded with measures aimed at Australia's economy. In May, Beijing halted imports of some Australian meat products, citing violations of customs requirements.

Soon after, it imposed extra tariffs on Australian barley, saying the grain was being imported at significantly low prices.

China accounted for more than a quarter of Australia's foreign trade in the 12 months through June last year. It has been a key factor in Australia's nearly 30-year run of economic vibrancy—a run that came to an abrupt end when the coronavirus pandemic hit.

As ties between Australia and China worsen, Tyrrell is looking for other markets for his wine. He says Japan, South Korea and Vietnam are the most promising options.

"I think anyone who's doing business in China at the moment is being careful," he says. "Australia has taken a position that we're not going to be pushed around. We'll see what happens. It'll slow down sales for sure."

According to Professor James Laurenceson, director of the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology Sydney, Australia needs to find the right balance between embracing and pressuring China.

"We're not going to choose between America and China," Laurenceson says. "That's not in Australia's national interest. We'll work with China, we'll work with America when their respective interests align with Australia's."

He adds, "China is the number one trading partner; it's not a sensible thing to start a trade war with your number one trading partner."

Impact on general public

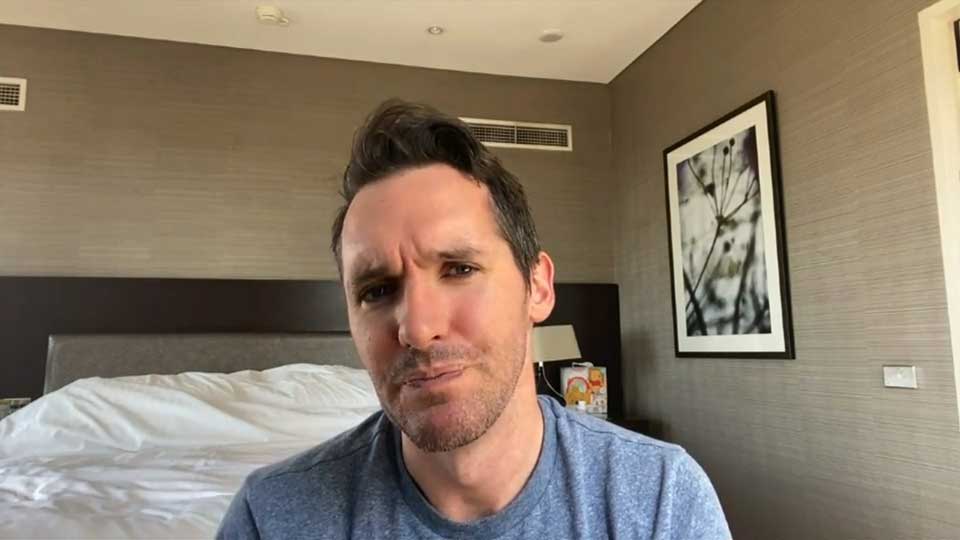

Last month, Beijing suddenly took aim at Australian journalists based in China. Authorities issued exit bans to Bill Birtles of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and Michael Smith of the Australian Financial Review, telling them they would not be allowed to leave the country. Both men took refuge on Australian diplomatic soil, while diplomats negotiated the lifting of the bans.

Birtles says he thinks the move was made in retaliation for an investigation by Australia's security agencies into suspected cases of Chinese interference in Australian domestic politics.

"It certainly was very noticeable to us that it was likely related to the Australia-China relationship," he says.

The incident came just a month after Cheng Lei, an Australian citizen and longtime anchor for China's state-run English news service was detained without charge. And last year, a Chinese-Australian writer, Yang Hengjun, was arrested in China for alleged espionage. He was charged earlier this month.

Laurenceson says these cases suggest the tensions between the countries are starting to affect ordinary members of the public.

"When you have journalists detained, then of course there's other groups in Australian society worried too," he says. "I'm expecting many Australian academics now will question whether they are willing to travel to China. People-to-people ties get affected as well. That's a disappointing development because historically people-to-people ties had been a real strength of the relationship."

Tyrell believes that ultimately, diplomats will find a way to salvage the relationship because it is not in the best interests of either country to damage trade relations.

"If you leave the sensible people to it, you'll normally come up with an answer that suits both sides, which is what we have to do," he says.

But in the meantime, he'll be looking to other markets for his wine.