In 2008, China faced a plastic problem. As the country’s economy developed, plastic bag use had become ubiquitous. Retailers gave them out for free, and because they were thin and tore easily, many consumers would throw them out in the streets after a single use. The problem was dubbed “white pollution” and the government took action. It banned the production and use of thin plastic bags and ordered retailers to start charging for bags of a thicker quality.

Just one year later, the government hailed the seismic impact of the surcharge. According to the National Development and Reform Commission, the number of plastic bags used at supermarkets and other retailers had fallen by almost 70%.

However, nearly a decade later, data showed that the effects may not have been as dramatic as the government claimed. In 2018, the China Zero Waste Alliance, a consortium of Chinese environmental organizations, surveyed nearly 1,000 retailers in nine major cities, including Beijing, Shenzhen and Shenyang. It found that only about 17% of retailers were actually charging for plastic bags.

A representative of an environmental group that took part in the survey, Sun Jinghua, said: “Shops see other retailers as rivals. So, if one shop charges for plastic bags while its rivals don’t, it thinks it may lose customers. The authorities can monitor major supermarket chains, but it becomes difficult for smaller businesses.”

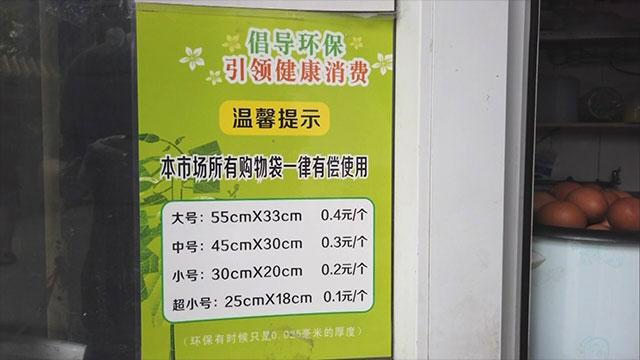

The measure is also being undermined by the cost of the surcharge itself. The prices of plastic bags of various sizes at supermarkets and smaller shops range from 0.1 yuan, about one cent, to 0.4 yuan, roughly six cents. These were not insignificant sums for the average consumer when they were first implemented. However, the prices have remained the same since, and as income levels have risen, they are no longer a burden for consumers. Experts say the cost will have to be doubled to one yuan, about 15 cents, if the surcharge is to be effective.

Plastic problem takes new shape amid coronavirus

The coronavirus pandemic has led to the emergence of a new kind of plastic waste problem, as people increasingly turn to food delivery services to avoid going to restaurants.

Delivery apps had already become popular in recent years, with restaurants and supermarkets developing their own platforms. As demand has grown, e-commerce giants like Alibaba have also dipped their toes into the sector, further fueling competition.

Since the start of the pandemic, motorcycles crowding in front of buildings at lunchtime is becoming a common sight in the business districts of major cities. Customers are notified on their smartphones when their orders arrive and go downstairs to pick up their meals.

As their platforms become more popular, delivery services are using more containers to keep the taste of the orders as close as possible to restaurant quality. For example, when companies deliver noodle dishes, they now place the soup, toppings, and noodles in separate containers. According to Chinese media outlets, delivery services use an average of 3.27 containers per order. In August, one of the country’s biggest delivery service providers received about 40 million orders per day, which would mean more than 120 million containers were used every single day.

“Placing each item in a container or a bag leads to waste,” says Sun Jinghua. “The government hadn’t accounted for the rise in delivery services back in 2008 when it implemented its plastic bag surcharge. So it has to come up with solutions for these new problems, along with private companies and the public.”

This January, the government unveiled a plan to completely ban the use of plastic bags at supermarkets and retailers in Beijing, Shanghai, and other major cities by the end of the year. It also introduced a ban on plastic straws at restaurants and a 30% reduction of plastic container use by 2025.

Since July, major cities have outlined measures they will take to adhere to the government’s new plans. But when Beijing has come up with sweeping regulations in the past, smaller communities have always drawn up their own rules.

There’s even a saying for this in Chinese: “The authorities have policies, but the locals have countermeasures.” This independent streak may be what led small businesses to flout the plastic bag surcharge for so many years, and it suggests that no matter how strict the government’s regulations, people will always manage to find a way around them.