People across the United States have been mailing Japanese flags to an office in Oregon. The banners are “heirlooms” kept by American families over the decades. Many are from World War Two battlefields and represent a life cut short.

The Oregon based non-profit organization the OBON SOCIETY takes mementos that veterans and their families want to return to Japan.

The OBON SOCIETY says items are pouring in faster than ever because people stuck at home during the pandemic are spring cleaning and finding them in their closets.

American troops often took Japanese soldiers’ belongings as trophies.The most common items were flags called “Yosegaki Hinomaru,” inscribed with names and messages from family and friends, wishing the soldier good luck. The soldiers carried them as amulets.

Making miracles

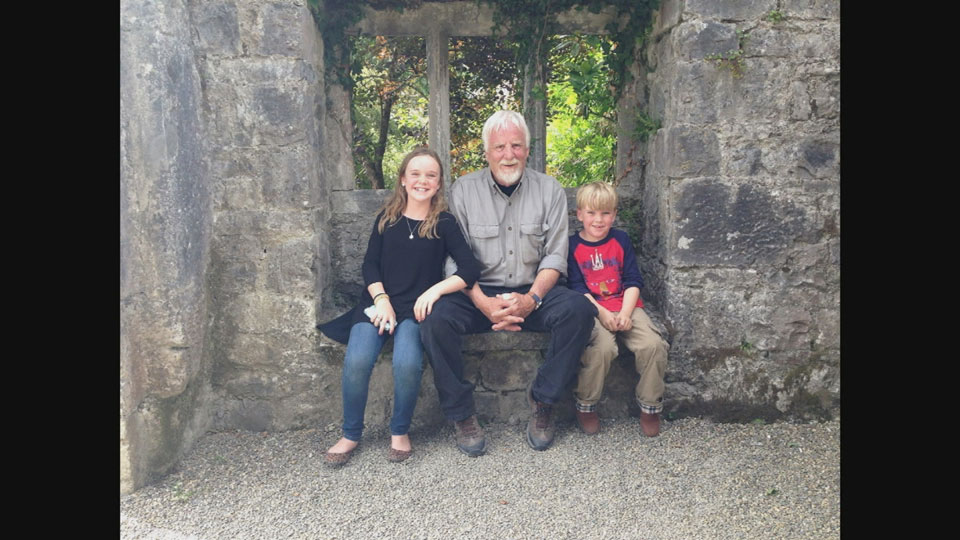

Keiko and Rex Ziak founded the OBON SOCIETY in 2009. Keiko's grandfather, Hirono Ichiji, went missing in action in what was then Burma, now Myanmar, during the war. Sixty-two years later, the family received his flag. She says it felt like a miracle, as though Ichiji’s soul had been longing to be reunited with his family and had finally come home.

“We thought we wanted to make more miracles for other families in Japan,” she says. Her husband Rex says they named their group after the Obon summer vacation period during which people welcome the spirits of ancestors back for a visit.

But it wasn’t easy for the Ziaks to explain the meaning of the flags to people in the US. Many thought they were military-issue, to encourage valor in battle. But the Ziaks have spent years telling people about the personal nature of the relics. Rex says the perception has changed and it’s made a big difference. When people understand what the flags represent, they are usually quick to say that the flags don’t belong to them, but to the original owner’s relatives.

From memory to history

The Ziaks say the pandemic is not the only reason the mementos keep coming in. They say people who inherit war memorabilia from those who actually fought in war often want to send the items back. They have no memory of the war, so their feelings about the mementos are less complicated. Rex says we are going through a transition where war goes from “memory” to “history.”

Among the many who have returned a flag is Willis Lee of New Mexico. His stepfather gave him a Japanese flag, apparently bloodstained and bullet-holed, back in 1963. He kept it in his dresser for decades. Lee doesn’t know how or where his stepfather got his hands on it, but he had long wanted to return it to the soldier’s family and knew what to do after reading about the Ziaks in his local newspaper.

Lee says it was one small thing he could do in the name of peace. And he wanted to teach his grandchildren the realities of the war. “It’s history, but we don’t want to repeat it,” says Lee. “And I’m not talking about our two countries -- I’m talking about the world as a whole. To me it was just an important gesture I could make.”

The OBON SOCIETY’s research team determined that the flag had belonged to Hirata Takejiro, who died fighting in the Philippines when he was 22. His niece, Ono Hiroko, was presented with it at a ceremony in July.

Ono's family never received Takejiro’s remains. “This is the only treasure we have from him,” she says. “I can’t think of this as anything but a miracle, after 75 years. I believe my uncle’s spirit must have wanted to come home after all these years.”

The phenomenon isn’t just happening on a personal level. Last October, a military museum in the US repatriated a Japanese flag that had been displayed for many years. The New Mexico Military Museum hosted a ceremony to turn over the flag to the OBON SOCIETY in the hope they would locate the relatives of the original owner and return it. Members of the military and civilians attended what was a solemn event.

It’s unclear how or when the museum acquired the flag, but it is now on its way home. Researchers located a relative of the original owner in Japan. Kenneth A. Nava, the Commanding General of the New Mexico National Guard, said it took a long time to reach the point of reconciliation, but he is delighted that the organization found the family. He also said he hoped to take part in a formal handover ceremony.

Other museums and universities across the US have begun to review their war collections, or to use them for education.

Flag of peace

“It’s an organic kind of wave that’s coming and we are just trying to be the point of contact in between to help them,” says Rex Ziak.

The group has returned about 370 flags to date, 120 of them in the last year alone. They say their aim is to increase the pace and return one flag for every day of the year.

Says Rex Ziak: “I think it’s more important in this world than ever before to demonstrate there can be peace in America and Japan. Enjoy peace, and other people in other parts of the world could do the same.”