Haishen, which means “god of the ocean” in Chinese, developed far south of Japan on September 1st. The Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) issued warnings well ahead of its approach as it was forecast to hit Japan with unusual strength. It rapidly intensified when the central pressure dropped from 970hPa to 925hPa within 24 hours on September 3rd. The lower the pressure, the stronger the storm. Measurements the following day had it at 920hPa, making it the strongest tropical system on earth this year.

Haishen plowed through the southwestern islands of Japan with full force on September 6th. It then passed west of Kyushu island while gradually weakening. The Goto Islands in Nagasaki experienced wind gusts of 214kph, the strongest on record for the area. Miyazaki Prefecture received 522.5mm in 24 hours, more than the average rainfall for the entire month of July.

Most of the injuries sustained in Japan as a result of Typhoon Haishen were caused by strong winds. Four people were hurt by broken windows in an evacuation shelter in the Goto Islands. Two people were killed, including a 70-year-old woman who was found dead in a gutter in Kagoshima Prefecture. A landslide in Miyazaki Prefecture left four people missing. At one point, power outages impacted more than 475,000 households in Kyushu.

Record Warm Waters

One of the reasons that Haishen grew so powerful is an unprecedented high ocean temperature. Surface temperatures in the Western Pacific have been about 2 degrees Celsius higher than normal over summer. According to a JMA report, one patch of ocean south of Japan had an average monthly temperature of approximately 30 degrees Celsius in August — the highest ever recorded. This is attributed to a Pacific high-pressure system that extended west, blanketing the waters with warm air. Because there were no typhoons in July, the undisturbed seawater stayed warm. That supplies typhoons with an abundance of vapor.

The warm ocean has helped a series of strong typhoons develop in the region since late August. On August 26th, Typhoon Bavi made landfall in North Korea with a central pressure of 965hPa. It was the third typhoon to hit the nation in recorded history. A few days later, on September 3rd, Typhoon Maysak struck South Korea. It was at 952.5hPa as it passed through Tongyeong City, the second-lowest pressure in South Korean weather data history, and just a nudge higher than the 951.5hPa brought by Typhoon Sarah in 1959.

What caused Haishen to weaken?

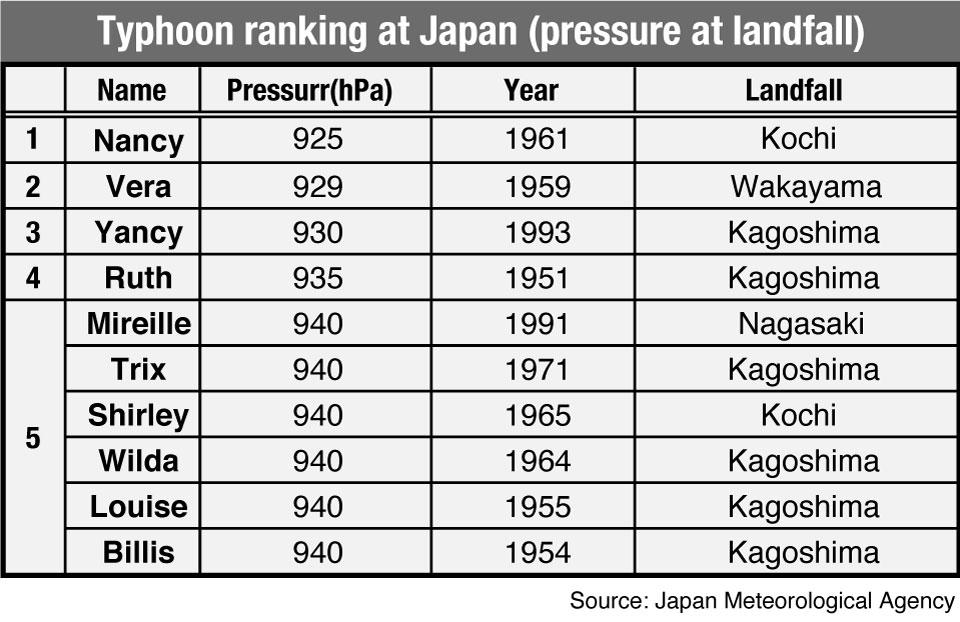

The JMA originally forecast Haishen to approach or make landfall in Kyushu with a central pressure below 930hPa. The two strongest storms in Japan’s history are Typhoon Nancy, with 925hPa at landfall in 1961, and Vera, with 929hPa in 1959. Meteorologists were ranking Haishen among the top three strongest storms on record. Fortunately, it did not make landfall, and its pressure dropped to 945hPa when it approached Kyushu. Gusts as high as 300kph were in the original forecast, but the maximum winds recorded were 214kph.

Experts suggest that a recent drop in sea surface temperatures over the East China Sea prevented Haishen from gaining its predicted strength. Typhoon Maysak had drifted over the ocean a week beforehand, stirring the water up and causing it to cool. Because clouds kept covering the ocean during that week, satellites were unable to detect accurate ocean temperatures. With that lack of information, Haishen was forecast to become stronger than it actually did.

Danger lies ahead

Like Maysak, Haishen also lowered ocean temperatures. The graphics below compare September 3rd and 8th, before and after Haishen. The typhoon stirred the water, bringing temperatures back down into the 20s. However, areas to the east are still measuring 30 degrees Celsius or higher. Studies show that temperatures of over 27 degrees Celsius intensify storms by feeding water vapor, meaning the potential for fierce typhoons remains.

September and October storms tend to track towards Japan. During the summer, a Pacific high-pressure system covers the archipelago, preventing typhoons from making landfall. However, as summer draws to an end, the high-pressure system recedes towards the country’s east. Most of Japan’s top ten typhoon disasters since 1951 occurred during fall.

If a new storm forms south of Japan in the next two months, and travels over the unusually warm ocean, the country faces the frightening prospect of typhoons packing unprecedented power.

Stronger, slow-moving typhoons

The JMA recently released a report showing that the number of typhoons hitting Tokyo has risen 1.5 times over the last four decades. Moreover, they have become stronger, and tend to move more slowly than in the past. In October last year, the greater Tokyo area was slammed by Hagibis, the wettest typhoon on record for the region. Hakone received over 922 mm of rain in 24 hours — a national record. Hagibis killed at least 90 people, making it one of the deadliest typhoons in recent memory.

How to prepare

Challenging conditions are a likely scenario in Japan for the next couple of months. Authorities encourage people to be prepared for typhoon season, and consider the following measures:

- Plan an evacuation route well ahead of time

- Create a family disaster plan

- Gather emergency supplies such as water, food and medicine

- Because of Covid-19, include masks and hand sanitizer in emergency packs

- Trim weak branches and trees from around the home and clear drains to avoid flooding

- Keep a list of information sources including the JMA, local governments, NHK, and install weather apps