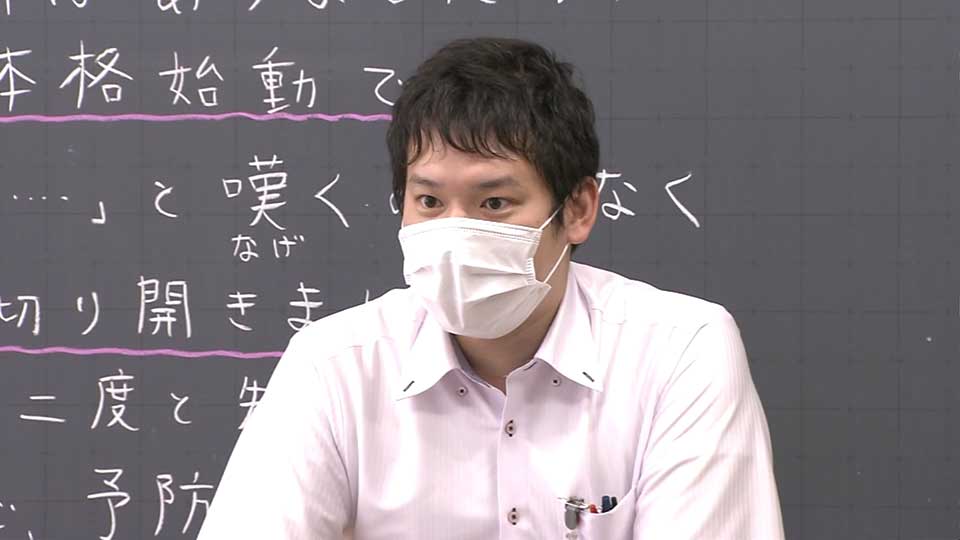

Junior high school teacher Muro Taichi is among those feeling the pressure. He is a social studies specialist at a city-run school in the coastal city of Toyama. Before the coronavirus, he taught a class in the morning, another in the afternoon, then oversaw the school's badminton club. When that was done, after his official hours ended, he had clerical work and needed to prepare for the next day's classes. Some days he was unable to head home until well past 8pm, and his overtime often topped 80 hours per month.

When the coronavirus hit, Muro's workload increased. He is required to carry out coronavirus prevention measures, including monitoring classrooms and corridors to make sure they are never too crowded. He disinfects the desks every day, and even has to clean the toilets. That used to be something the pupils took care of, but it is a task that is now the teachers' responsibility in a bid to minimize infection risk among the student body.

Muro is also concerned that students are behind in their studies because of school closures earlier this year. In February, Prime Minister Abe Shinzo asked all elementary, junior and high schools in the country to shut temporarily. Muro's school reopened in June, by which time students had missed about 20 hours of study per subject.

To help the students catch up, the school shortened its summer break from 37 days to just 10, but that isn't enough to make up for months of missed study.

Muro says if they speed up the pace of classwork, some students will fall even further behind. To support them, he has created his own educational materials and papers. With the badminton club open again, Muro is busier than ever.

"I sometimes have to come to school on weekends to go over the papers that students submitted," he says. "It would be a lie if I said I don't feel any pressure or stress."

In a survey conducted by the Teachers' Union in Toyama prefecture in July, more than 80 percent of teachers said their burden has increased after the coronavirus outbreak, largely because of the extra things they have to do to prevent infections.

"The coronavirus has made teachers exhausted at a time when schools are already struggling with a labor shortage," says Professor Sakuma Aki of Keio University, an expert on educational administration. She believes the answer is to hire more, but acknowledges that's not easy to do.

"The teachers' licensing system has to be more flexible to make it easier for former teachers to come back," she says. "And we need to do more to bring in workers from outside educational circles."

The central government is offering subsidies for schools to hire extra staff to handle anti-virus measures, but those positions are proving hard to fill.

Meanwhile, teachers like Muro Taichi are working overtime…in his case, to the tune of 100 hours for July. He says he is doing his best. "The more I prepare for class, the harder the students study in class," he relates. "If teachers are too busy and have no time or energy to spare, students can sense that."