The Navajo people have suffered through the worst coronavirus outbreak in the United States, with a higher per-capita rate of infections than any US state. Currently, the reservation of about 170,000 people has seen more than 9,000 cases and over 460 deaths.

The reasons for the severity of the outbreak on the Navajo Nation are complex and varied, but most, if not all, can be traced back to the history of colonialism and violence perpetrated by the United States against Navajos and other indigenous peoples.

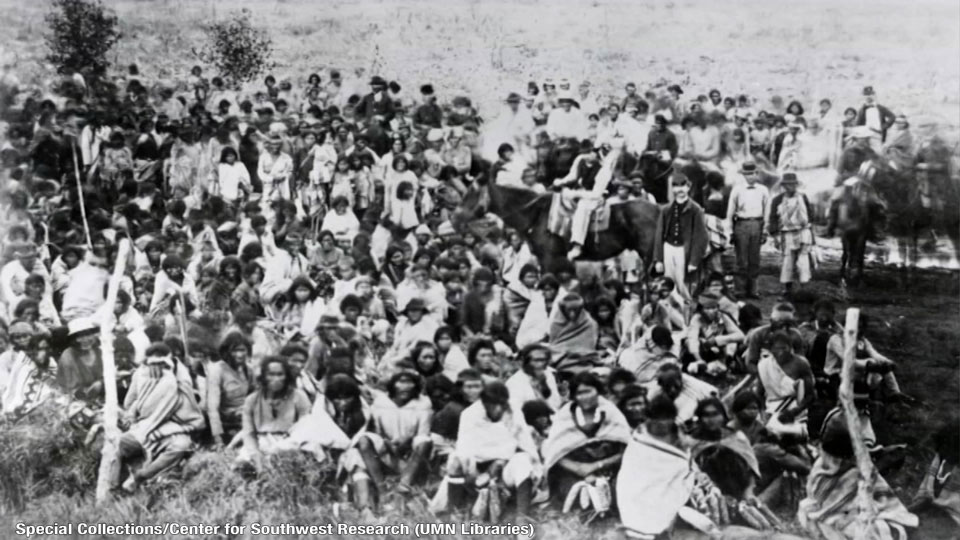

The vast reservation, roughly the size of West Virginia and spanning large chunks of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, was established on a portion of the traditional Navajo homeland following the Long Walk, a campaign of ethnic cleansing and forced relocation of the Navajo people in 1864. Hundreds died during the 400-mile march to an internment camp known as Bosque Redondo, and an estimated 1,500 more people died in the camp over the next several years.

Eventually, the United States government agreed to return some of the land to the Navajo, and promised to assist with building infrastructure and providing health care. But more than a century and a half later, many of the US government’s promises are still unfulfilled.

“They starved us out. They burned our homes and our crops… and brought us here. They got us to our very weakest state,” said Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez. “There were some promises made there that the federal government would help with infrastructure, education, health care… I can list a whole line of broken promises. We'll be here all day.”

And the legacy of those broken promises is a nation that still lacks basic infrastructure that most Americans take for granted. According to Nez, 30 to 40 percent of Navajo residents do not have running water, a fact which has helped accelerate the spread of coronavirus, since many Navajo are unable to regularly wash their hands.

Higher mortality rate

Another problem is that the reservation has only 13 grocery stores, meaning residents have to travel far from their homes to meet their basic necessities, and it’s difficult to maintain social distancing while shopping because so many people have to rely on just a few stores to shop for food. The lack of availability of healthy food has also led to high rates of diabetes and other conditions that make people particularly vulnerable to the virus, leading to a mortality rate on the Navajo Nation of over 5 percent for COVID-19 patients, while the rest of the US has an average mortality rate of a little over 3 percent.

Perhaps the most obvious modern-day example of those broken promises was the Trump administration’s failure to distribute money owed to tribes from the coronavirus stimulus package known as the CARES Act, which forced the Navajo and other tribes to sue the federal government for their fair share of the money, and denied federal funding to the Navajo Nation and other reservations in the crucial early days of the pandemic.

Dr. Farina King, a member of the Navajo tribe and a history professor at Northeastern State University in Oklahoma, said the legacy of colonialism, broken promises and ongoing racial violence in the Navajo Nation has created modern-day conditions that allow the coronavirus to spread easily.

“We've set the perfect scenario for that virus to wreak havoc, to attack the people, a people who have for generations been colonized, been attacked, suppressed, even in the sense of our very existence,” she said.

But the story of the Navajo Nation is not just a story of tragedy, it’s also a story of hope and human kindness, and a story that could point to a way forward for the rest of the country as it struggles with the ongoing effects of the coronavirus.

Pulling together

Numerous relief and mutual-aid groups have sprung up since the start of the crisis, distributing food, water and other much-needed supplies to underserved communities on the Navajo Nation. In Pinon, Arizona, a rural community on the Navajo Nation, the local high school gym has been converted into a distribution point for food boxes for community members. Funded by a group called the Navajo and Hopi Families COVID-19 Relief Fund, the boxes contain two weeks’ worth of food for a family of four, including eggs, meat and fresh produce, as well as staples like rice and beans.

Jonathan Allen, who works for the high school and helps distribute the food boxes, said it is critical to ensure high-risk families can obtain food without having to risk entering a crowded supermarket.

“We have so many people that live far out there, you know, an hour's drive in the middle of nowhere. And you would think, you know, they'll never get COVID out there. But everybody comes to this one place to get food,” he said. “And that's where this food distribution, I guess, became paramount. Like this is actually making a huge impact on lives within our community.”

And the younger generation of Navajos have also stepped up to tackle the crisis on the Navajo Nation. Members of a youth-led mutual aid group called K'é Infoshop work 12 hours or more nearly every day, without pay, distributing food, soap and other basic supplies to Navajo people experiencing homelessness and others who are particularly vulnerable. Shandiin Yazzie, an organizer with the group, said “K'é” is a Navajo word that roughly translates to “kinship,” a fundamental principle for the Navajo people.

“K'é does not discriminate,” she said, emphasizing the group’s belief that everyone is deserving of shelter and basic necessities. She said there are no reliable statistics on homelessness on the Navajo Nation, and it’s become harder to track since the start of the pandemic. But the group’s members continue on, often serving 30-50 meals during their Saturday meal services.

Cultural values

Keana Kaleikini, who holds a Master of Science in Public Health from Johns Hopkins University and is a co-organizer with a group called Protect Native Elders that distributes supplies to Navajo residents in need during the pandemic, said that the Navajo people have shown incredible strength and resilience throughout the crisis.

“In our cultural values, it's intrinsic in us to serve our community,” she said. “I think that other nations right now are looking towards the Navajo Nation and their measures that they have taken to flatten the curve here, essentially, while everyone else around us is still spiking.”

And unlike in the wider United States, Kaleikini said, the coronavirus isn’t seen as a partisan issue, which has helped Navajos mount a strong response to the pandemic.

“On the Navajo Nation, the pandemic hasn't been politicized and any kind of preventive measures that have been recommended by the tribal government have been taken without much resistance, as we've seen on the federal government level. And so I think that they're just doing a fantastic job,” she said.

While infection rates continue to climb in states around the US, including those bordering the reservation, the Navajo Nation has effectively flattened the curve, with average new cases hovering around 30 a day compared to more than 100 per day in early June. President Nez and others credit the strong will of the Navajo people, as well as their collective resolve to combat the virus together combined with a strong response from the Navajo government, for the Navajo Nation’s success.

“We mandated our citizens in April to wear a mask in public. We did stay-at-home orders, curfews and also the shelter in place,” he said. “That and the Navajo people, of course, listening to public health professionals and the first responders and all these recommendations that we incorporated into public health orders, I truly believe have flattened the curve.”

But the Navajo Nation isn’t out of the woods yet. Of particular concern to Navajos is the large spike in Arizona, which recently passed 180,000 cases. There’s high potential for the spike in Arizona to lead to a renewed increase in case counts on the Navajo Nation, as tourists and visitors may disregard requests to stay off the reservation and spread the virus on Navajo land. Many Navajos also rely on grocery stores off the reservation for food and supplies, and may be exposed to the virus during shopping trips.

But regardless of how the situation evolves going forward, Nez and many others are certain the Navajo people will respond to it with strength, unity and care for their families and neighbors.

Crisis in Navajo Nation