The law criminalizes four types of activity or behavior: secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign or external forces. Each are punishable with a maximum sentence of life imprisonment.

The law also allows the Chinese government to set up a security agency inside Hong Kong. It will exercise jurisdiction in complex cases involving foreign countries or external actors. In such cases, Chinese laws will apply in the investigation, prosecution, and trial.

Hong Kong’s pro-democracy forces have been left in disarray by the law’s passing. Many political groups, including Demosisto, which was founded by the prominent activist Joshua Wong, have disbanded.

“The fear that the fight for democracy in Hong Kong has become a life-or-death matter can no longer be considered preposterous,” Wong tweeted. “I will implement my beliefs as an individual from now on.”

The law seems to be aimed at neutering the wave of youth activism, led by the likes of Wong, that has energized the city’s protest movements in recent years. It not only makes it difficult for pro-democracy groups to mobilize, but also includes measures to prevent the nurture of future generations of activists.

It says, “The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall promote national security education in schools and universities and through social organizations, the media, the internet and other means to raise the awareness of Hong Kong residents of national security and of the obligation to abide by the law.”

Professor Kurata Toru of Rikkyo University in Japan, an expert on Hong Kong politics, says the law is not only Beijing’s response to the pro-democracy protests; it is also a show of strength to the mainland.

“The Xi Jinping administration is trying to demonstrate its strong leadership to the people of China,” Kurata says, as faith in his governance has been tested by the economic effects of the coronavirus and international criticism of his handling of the early stages of the pandemic.

The law applies to every Hong Kong resident, regardless of nationality. Furthermore, it also covers acts committed by nonresidents outside of Hong Kong. This means anyone in the world could theoretically be prosecuted for their actions outside of Hong Kong.

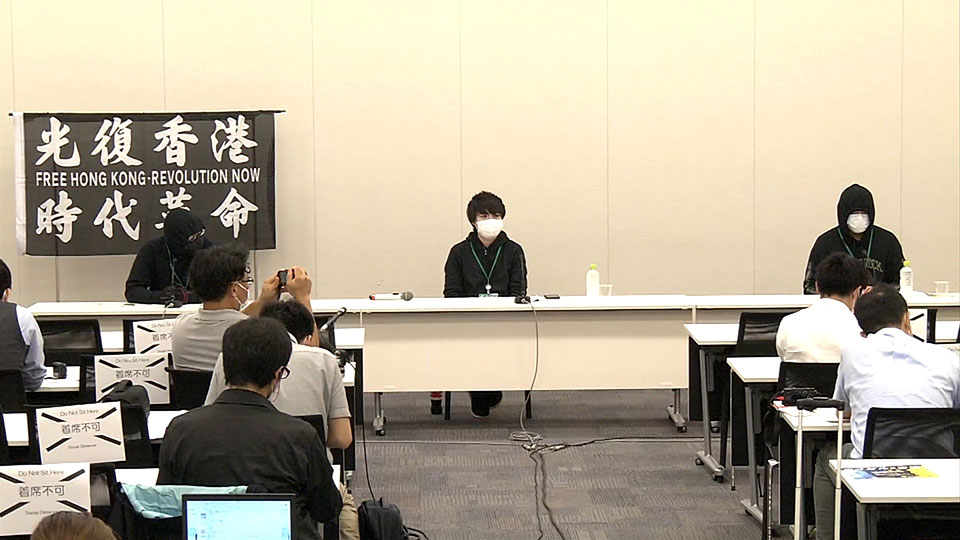

Concern about the law’s expansive jurisdiction was evident at a press conference held on Wednesday in Tokyo by Hong Kong citizens living in Japan. Speakers kept their faces covered as they requested the Japanese government to support the many people who may be looking to emigrate from the territory.

“If we don’t speak up now, we will have succumbed to the government, and that’s one thing I won’t do,” said one speaker. “As a Hong Konger, I don’t want to relinquish my beliefs and values.”

On June 30, the UN Human Rights Council held a meeting in Geneva at which 27 countries, including Japan and the UK, issued a joint statement expressing concern about the law. It said the legislation infringes upon the “one country, two systems” policy and will be detrimental to the protection of human rights. It goes on to request that Hong Kong and China respect the rights and freedoms that have long been enjoyed by residents of the city.

China did not respond favorably to the statement. At a press conference on July 1, Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian said, “A small number of foreign forces have a guilty purpose and interfere in the name of human rights. It is based on an arrogant prejudice.”

In Hong Kong, many residents are now afraid to exercise the freedoms of speech and assembly they had enjoyed just days earlier. When a similar security law was passed on the mainland in 2015, many human rights lawyers and activists were immediately detained.

“The legislation is written in the name of national security,” says Professor Kurata. “But it is actually being used to block political opposition.”

While Hong Kong nominally remains governed under the “one country, two systems” policy, the security law will likely herald a new era of a drastically different way of life in the city.