If your clothing says “Made in China”, there’s a good chance it comes from Guangdong. By some estimates, the province produces a quarter of all garments made in the country. The abundant employment opportunities make it a magnet for migrant workers. But it has been devastated by the economic effects of the pandemic, and many of these workers are now out of work.

In early April, the streets of a town in Guangdong dubbed Hubei Village because of the large community of migrants from the central province of Hubei, were crowded with people looking for jobs.

The pandemic has affected every aspect of the Chinese economy. Domestic consumption has slumped, overseas orders have plummeted, and factory lines in manufacturing hubs like Guangdong have ground to a halt.

Most migrant workers were back in their hometowns for the Lunar New Year holidays when the virus started to spread and travel restrictions were imposed. These measures were eased in late March and the Chinese government deployed trains and buses to shuttle people back to their jobs. But for many, there were no jobs to return to.

Migrant workers giving up

By the end of April, there were crowds of people with heavy luggage at bus stops throughout the town. They were heading back to their hometowns. It was a scene more redolent of the New Year holidays than late spring.

One man in his 50s, who gave only his surname, Xiong, said he tried going back to work at the end of March but found his job no longer existed. He tried looking for work elsewhere but the most he could get was a handful of days so he decided to go home.

“I can’t pay the rent and have nothing to live on,” he said. "My wife and children are waiting at home, and it’s tough to go back without making any money. But I have no choice.”

A bus packed with people bore a government slogan reading: “Resumption of Operation and Production.” It was one of the buses that had been used to bring migrant workers back to Guangdong in March.

“On sale” notices everywhere

By the middle of May, there were signs that things were getting even worse. Notices in the streets offered to sell the rights to factories.

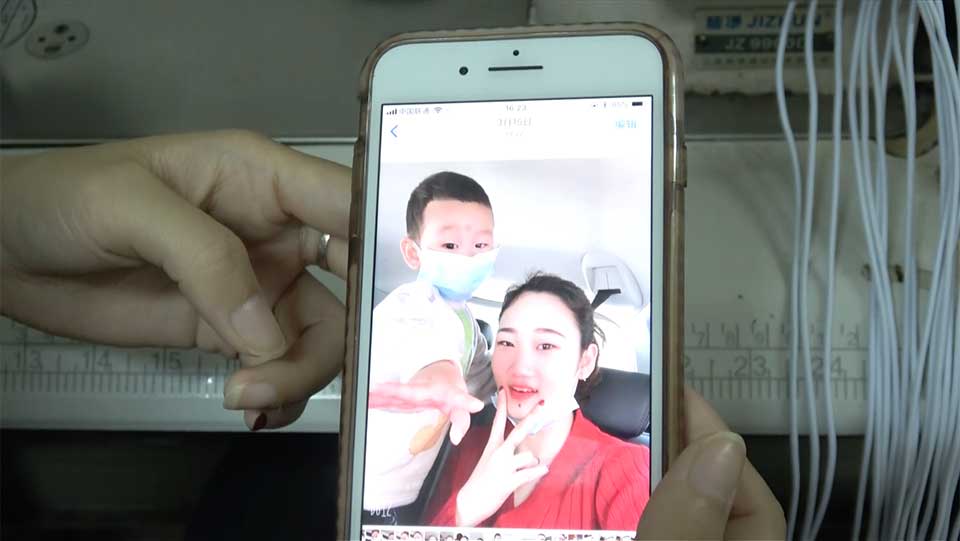

A man in his 20s, who gave only his surname, Xu, is from Hubei Province. He had been running a small garment workshop in Guangdong with his wife.

He says orders dropped by more than 30% this year and it was becoming impossible to keep up with rent, and so they decided to try to sell and move back to their hometown.

“Living expenses are higher here and our landlord won’t give us a break,” Xu says. “We don’t know what to do. It seems that half of the people of Hubei Village have already gone home.”

Signs of unrest

When China’s leaders spoke at the annual National People’s Congress in May, they repeatedly stressed the importance of addressing the employment issue. Their worry is that if frustration builds, the people could direct it at the government.

That may already be happening. In late April, media in Hong Kong reported on protests staged by the owners of small factories in Hubei Village demanding that the authorities cut rents. A video obtained by NHK shows crowds of people in the streets chanting: “lower rents!” and “rent relief!”

The official jobless rate in China was 5.9% in May. But that number only includes residents of urban areas, not the migrant workers who have returned home. China-based brokerage Zhongtai Securities estimates that the real number is above 20%, with more than 70 million now jobless throughout the country due to the pandemic.