Suppressed early warning

The death of a doctor is creating uproar across China. Li Wenliang sounded the alarm about a mysterious pneumonia outbreak in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, before the authorities acknowledged the spread of the coronavirus.

The 34-year-old sent the message urging caution to an online group chat with fellow doctors on December 30, 2019. But he was punished by police monitoring the internet for what they described as spreading "false" information.

Li was later infected with the virus himself and died of pneumonia on February 7. While in hospital, he told news site Caixin in late January that human-to-human infection had been occurring by January 8.

Many people believe that if the authorities had listened to his warning, the virus would not have spread as it has. When his death was reported, criticism of the government exploded online.

This prompted Beijing to reverse its stance and send condolences to Li's family. And, in an apparent attempt to head off criticism, the government sent a team from the country's anti-corruption body to Wuhan to investigate how the authorities had handled the issue.

Politics before virus education?

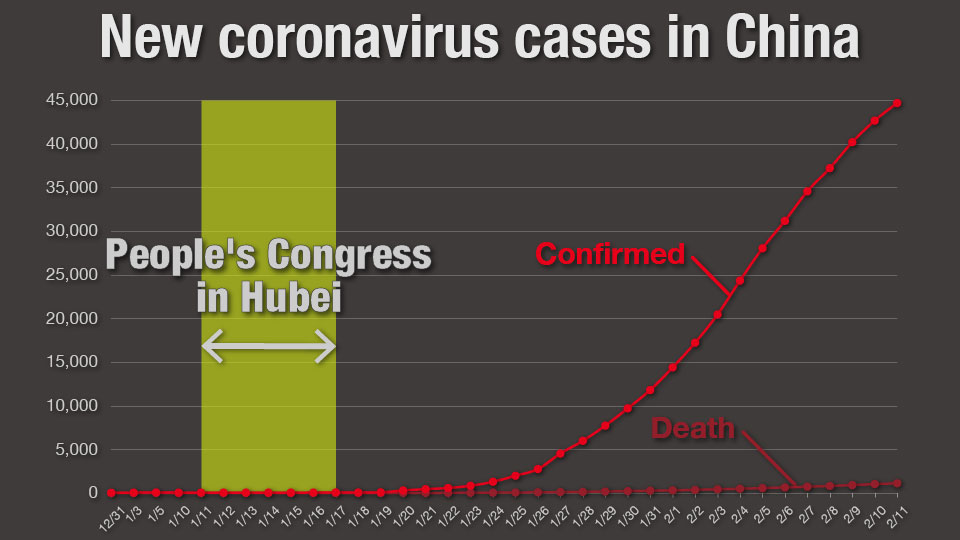

Authorities in Wuhan made public on December 31 the outbreak of pneumonia with unknown causes. At the time, they revealed 27 people had developed symptoms. On January 11, they said that 41 people had contracted pneumonia, and reported the first death. But the number of patients remained almost unchanged in government announcements. From January 19, however, the number began to rise significantly -- a seemingly unnatural shift.

No convincing explanations have been given, but there's one thing that is certain -- the People's Congress was underway in Hubei between January 11 and 17.

Professor Ichiro Korogi, an expert in Chinese politics at the Kanda University of International Studies, says the government might have intentionally withheld information about the infection for the sake of political stability.

In fact, media reports say measures against the new coronavirus were not on the agenda at the Congress. As a result, no sense of crisis was shared with the public, allowing a traditional event called Wan Jia Yan to go ahead in Wuhan on 18 as scheduled, prior to the Lunar New Year. The event, attended by tens of thousands of people, could have accelerated the spread of the virus.

Dearth of information

It was not until January 20 that President Xi Jinping instructed relevant departments to swiftly release information on the spread of the infection. But at the same time, he ordered efforts to control public opinion to be stepped up.

In China, the rapid increase of new infection cases has continued and the number of deaths topped 1,300 on February 13.

But Chinese media are focusing on the government's efforts to contain the virus. Extensive coverage has been given to messages issued by high-ranking government officials outside China to encourage the country and the many volunteers helping out. It appears the media are doing all they can to prevent people from developing a negative impression of their government.

Furthermore, media in other countries say some citizen journalists have been detained by Chinese authorities or gone missing after sharing footage of hospitals in Wuhan.

More than one voice

The Chinese authorities are stepping up their information control out of fear that people could vent their anger on the government.

The Xi administration has faced many headwinds recently, including an economic slowdown caused by trade friction with the US, a landslide victory for the pro-democracy camp in Hong Kong's district council elections, and the reelection of Tsai Ing-wen of the Democratic Progressive Party in Taiwan's presidential election.

The spread of the coronavirus has added to that and created a strong sense of crisis among Communist Party leaders. The painstakingly established authority of President Xi could even be shaken.

So far, the number two in China's leadership, Premier Li Keqiang, has been dealing with the issues surrounding the coronavirus on the frontline. He visited Wuhan on January 27 as the leader of the central government's anti-pneumonia team.

In contrast, there have been few reports to speak of about President Xi's moves, except for a visit on February 10 to a medical facility in Beijing holding pneumonia patients.

Up to now, the Xi administration has tackled problems by launching small groups with Xi at the very top. In other words, authority has always been concentrated in Xi. But that is not the case this time around.

Professor Korogi says that if they fail to contain the spread of the virus, President Xi may place the blame on Premier Li to save his own skin.

Information control by the Chinese government is making the people increasingly frustrated. But it doesn't seem to be doing anything to protect lives, which is supposed to be the government's top priority.

Before he died, Li Wenliang told a Chinese media outlet that there should be more than one voice in a healthy society. He went on to say that he couldn't support excessive intervention by the authorities.

Those remarks have since spread widely on social networking sites in China. And more than 50 people, including academics, have issued a statement calling for freedom of speech, saying the spread of the infection was caused by suppression of information, making it a man-made disaster.

Will the Chinese government be able to accept Li's appeal and release information willingly to help contain the virus? That's the crucial question for increasingly fearful people in China, and around the world.