Hard to meet mother

Akimi, a pseudonym for a woman in her 40s, says she noticed her mother's personality changing as the coronavirus pandemic went on. Her mother lives in a different city and, initially, would send advice about disinfecting and offering to send masks. But as time went by, the messages grew more intense and fearful.

"She would call me talking about being overwhelmed with anxiety, saying, 'What is going to happen to us? It's so hard not being able to see my grandchildren,'" Akimi recalls.

"But then her anxiety suddenly disappeared. She said, 'I was deceived. The coronavirus was actually created by powerful people. There is no need to be anxious.' She was in good spirits, which surprised me."

Later, her mother began to tell her that "this world is run by the Deep State, a dark organization," which "kidnaps and traffics children." By the autumn of 2021, she had become deeply committed to the ideas of the American conspiracy theory group QAnon.

Akimi played us an audio recording of a phone call with her mother.

Mother: "PCR tests are also dangerous. The swabs they put in your nose have microchips on them, and they fall out of your nose and into your intestines." "There is a facility underground in Japan where kidnapped children are kept, and the US military attacks them from the sea to free them."

Akimi: "Where did you hear about that? It's not on the news, is it?"

Mother: "On YouTube or on the internet. All Japanese media are part of a dark organization."

Akimi suspects that her mother stumbled upon videos espousing conspiracy theories while searching anxiously for information on the pandemic. And the ideas have driven a wedge between them. Akimi says she finds it hard to hear her talk these days, so texts and phone calls have become less frequent, and she tries to avoid meeting her in person.

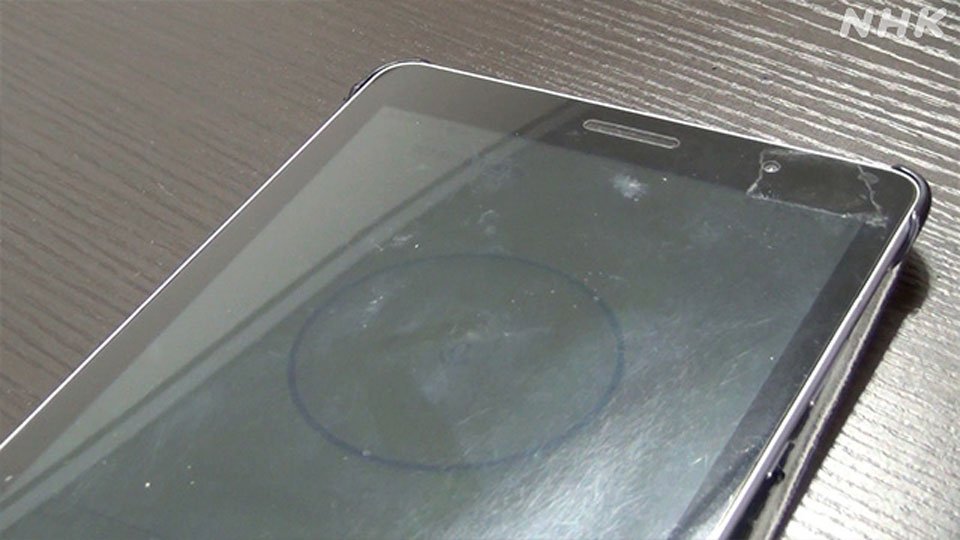

These days she is most concerned about the impact the ideas are having on her mother's finances. One of her mother's favorite online influencers has been telling people that "the battle between light and darkness will soon end with the victory of light," and warning that it will upend the currency market. The influencer is urging people to purchase Iraqi dinar among other currencies.

Akimi doesn't know exactly how much her mother has invested — the influencer warns followers never to talk about it, even to relatives — but she believes it is in the region of about 7,000 dollars.

"My mother thought she was investing," says Akimi. "She told me she would give me the money to buy an apartment because the dinar's value would increase 1,000-fold. I feel like I've given up on my mother. The theories seem to be my mother's emotional support, and I even sense it has become like a religion now in the way she talks about them."

The National Consumer Affairs Center of Japan has long warned about the Iraqi dinar, saying there have been a series of investment problems.

The impact on children

Sakura, a pseudonym, is a housewife in her 40s troubled by her husband's recent words and actions. About three years ago, a bad investment sent him into debt and prompted him to binge on conspiracy videos on YouTube. One claimed that the 2011 earthquake in northeastern Japan was man-made. Another said that all medicines are poisons created by doctors and pharmaceutical companies to make money.

Sakura says her husband is usually a good father, taking care of the household chores and playing with their children.

But she can no longer watch news on the television with him because he always tries to explain "the story behind the story." He also complains about the their children's education. He says their perception of history is manipulated and they should be suspicious of textbooks.

Sakura wants her children to think for themselves, and she is worried their development could suffer by having parents with such disparate views of the world.

The key word is 'living together'

Professor Nishida Kimiaki of Rissho University, an expert on cults and mind control, says conspiracy theories can take root in a person's mind in much the same way as a cult recruits followers.

1. The person is often isolated and suffering

Nishida says people who are in trouble, being ostracized or failing in some way are likely to embrace someone who tells them that they are not to blame and that the world is being unfairly distorted by external factors.

2. "Inside knowledge" boosts self-esteem

Nishida says people are attracted to the notion that they are privy to the world's secrets, and it make them more self-assured.

3. Affirmation within the group

Nishida says believers are likely to tell others "the truth", seeing it as a good deed. When people close to them reject the ideas, the believers look online for fellow believers and they reinforce each other's views.

He says it is not easy to convince people to reject the theories they have embraced, and that the key is to focus on acceptance and coexistence.

Nishida adds that it is important to accept people regardless of their values. He says we should not dismiss them, but we can ask that they refrain from imposing their values on others.

Nishida suggests looking at what brought about the suffering or difficulties that triggered a person's obsession with conspiracy theories.

He says the way to break the grip of a cult or a conspiracy theory is to address the root problem, connect with the person, and provide them with an alternative route to self-affirmation.

"It may not be easy to respect someone forcing his or her ideas on you," says Nishida.

"But trying to live in harmony with someone who has a different view of society and continuing to treat them with an attitude of 'come back here whenever you want' is the key to preventing the breakdown of families."