Eelgrass restoration as a blue-carbon initiative

In mid-November about 50 people, including parents and children, gathered at the port in Miyagi Prefecture's Shiogama to help with an effort to revive eelgrass in Matsushima Bay.

Expanses of eelgrass in relatively shallow sea areas act as a nursery, refuge, and breeding ground for a wide variety of sea life. The plant also absorbs carbon dioxide in the process of carrying out photosynthesis.

Eelgrass once thrived in Matsushima Bay, but most of it was lost when the seabed was scoured by the massive tsunami of 2011. Local fishers and other concerned citizens have been working to bring the eelgrass back to life.

The recent event saw participants sandwiching eelgrass seeds and mud between sheets of coconut fiber.

The resulting mats, 100 in all, were taken about a kilometer offshore and sunk. If all goes to plan, in a year's time the grass will have put down roots and grown fronds about a meter in length.

"Before the earthquake, Matsushima Bay was a rich sea full of eelgrass, but the entire bottom of the bay was lost," says event organizer Ito Yoshiaki. "Eelgrass absorbs carbon dioxide and emits oxygen, which contributes to environmental protection, so we aim to continue to focus on eelgrass restoration."

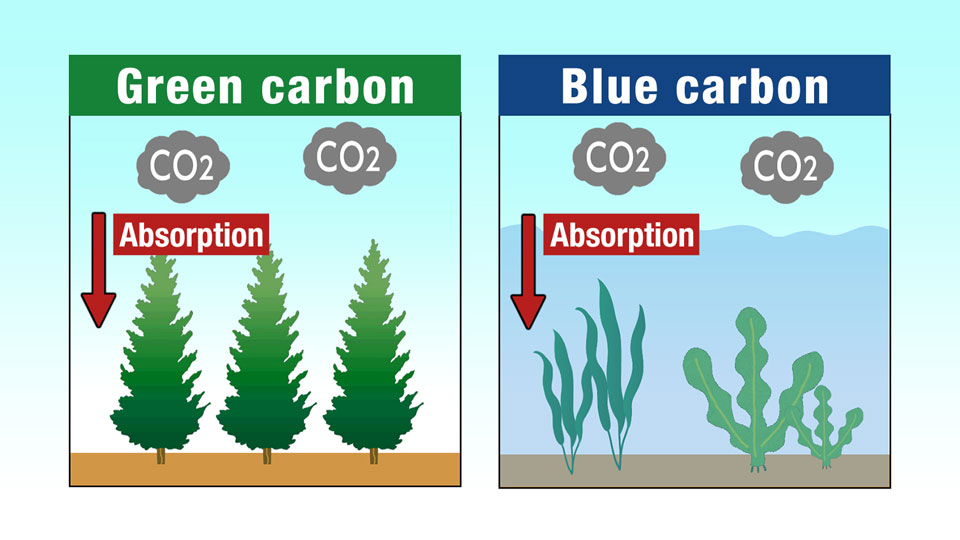

Shades of absorption

Efforts to restore marine ecosystems such as the one in Matsushima Bay offer an ideal combination of nature conservation and carbon absorption.

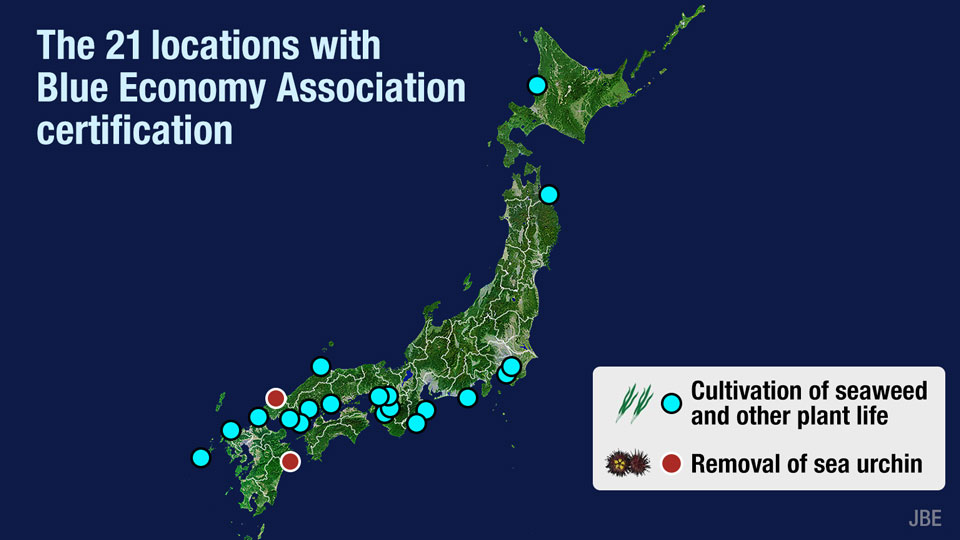

Three years ago, local governments and other bodies certified by the Japan Blue Economy Association began a blue-carbon trading scheme. This allows companies and organizations to support such efforts and offset their own carbon emissions.

The association had certified 21 locations around Japan as blue-carbon sites by the end of fiscal 2022 and says that sponsorship had been secured for the sequestration of more than 3,700 tons of carbon.

In Hannan City, Osaka Prefecture, a local fishery cooperative and an elementary school are working together to plant eelgrass. Funds raised from the trading scheme have been used for ocean conservation activities and other purposes.

In Oita Prefecture's Nagoya Bay, meanwhile, an effort is underway to restore seaweed by removing sea urchin, which can overbreed and do severe damage to kelp forests and other habitats. This imbalance is known in Japanese as isoyake. The spiky creatures are raised in tanks on shore so they can be sold on when they are ready for market.

For local governments, the funds obtained can be used for activities aimed at giving a boost to the economy and conserving nature.

Blue carbon-oyster farming

Oysters are also getting a blue-carbon rebrand. The mollusks are a specialty of Minamisanriku Town in Miyagi Prefecture.

Oysters are cultivated on cords that dangle from floating racks. Kelp and other types of seaweed attach themselves to the racks and cords. The town is seeking blue-carbon certification for the carbon dioxide absorbed as a result.

It would be the first such certification in Japan. Officials are hopeful that being acknowledged as a blue-carbon site will help revitalize the local economy.

"We are now in an era in which funds can be obtained through proper management of natural capital," says Kondo Michio, a professor at Tohoku University's Graduate School of Life Sciences. "By making good use of the nature that they have at their disposal, local communities can also improve the direction of the economy."

And there may be more good news about oyster farming. DNA analysis indicates that as many as five fish species, including goby and ayu, live in and around the seaweed-laden oyster racks.

Municipal authorities believe that oyster cultivation helps to maintain the marine ecosystem, in part by providing homes for small fish that have suffered habitat loss due to isoyake. They aim to have this ecological upside added to the list of features that merit blue-carbon certification.

"It is not a natural habitat for the fish, but they live there because they have found it a good place to live. It is an unexpected byproduct of oyster farming," says Kondo.

According to the Blue Economy Association, a higher value could be assigned to oyster racks that can be shown to provide fish habitat, potentially bringing in more funds. Minamisanriku aims for certification in February of next year.

Suzuki Shota of the Minamisanriku Nature Center says, "If we can show that oyster farms are not only producing shellfish for market but also maintaining the health of the sea, it will be a real fillip for the aquaculture industry."

The rewards of blue carbon could ultimately extend well beyond any one industry to the planet as a whole, helping to slow the steady march of climate change and avert its worst consequences. They also promise an exciting new chapter in Japan's vital relationship with its surrounding seas.