The problem for the firm, which manages more than 40,000 rental properties across Fukuoka Prefecture, is that permission can only come from the legal heirs, and in many cases the company is unable to track them down.

As Japan's population ages, the number of older renters continues to rise and, in turn, the number of such cases grows.

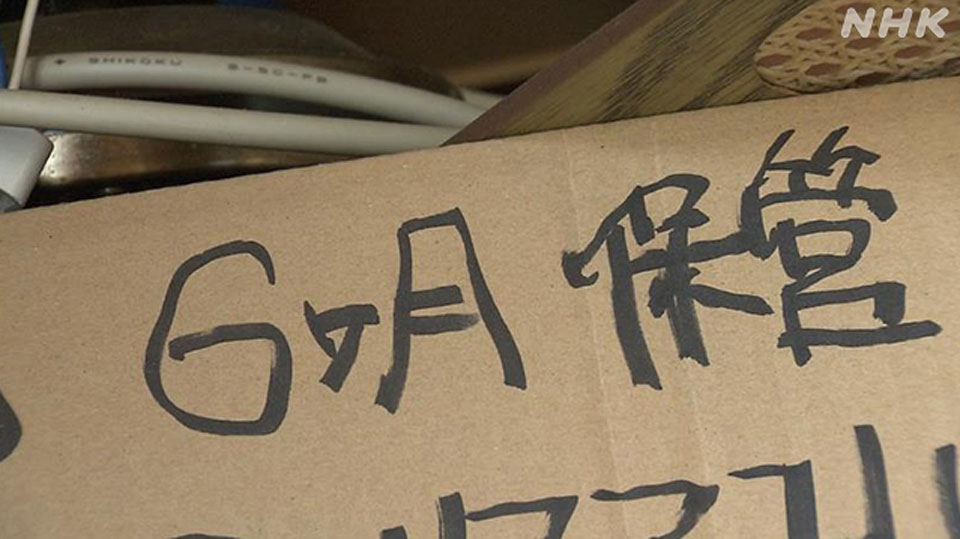

So too does the financial burden on the firm, which has no choice but to rent out storage space to accommodate the ever-growing mountain of unclaimed effects.

The situation is worse still for owners who can't afford storage space and are forced to keep belongings in their properties while they search for heirs, sometimes for years, making it impossible to sign new tenants in the meantime.

Landlords' legal quandary

Kakumoto Atsushi, a landlord who owns an apartment building in Fukuoka Prefecture, recalls a case where a female tenant in her 80s fell ill and died. Despite extensive inquiries, he couldn't locate a next of kin.

At first, Kakumoto was unwilling to risk moving the woman's belongings, leaving them in the apartment in case someone showed up to claim them. He was concerned that shifting them to another site without permission would risk a legal dispute. The items sat there for three years. He put them into storage for another two years, then disposed of them altogether ― at considerable expense.

"I never imagined it would take so long," he says. "The whole experience took a big chunk out of my income."

"If apartments are left cluttered like that for years, it can hurt the value of the property. I think landlords should be allowed to dispose of items when they're not claimed within a certain period."

Nowhere left to turn

So endemic has the problem become that some landlords are reluctant to entrust their properties to elderly tenants.

A 73-year-old man in the Kanto region discovered this to his shock when he inquired about a rental, only to learn the real estate agency wouldn't consider his application because he didn't have a guarantor. The agency said the cost of dealing with left-behind belongings had become too great a burden, so it would no longer deal with elderly applicants unless they had someone to vouch for them.

The man ended up living in his car for six months. Eventually his local government office connected him with an organization that helps locate housing for people in the same predicament.

"Many people who have no relatives, or who are estranged from their relatives, find it hard to get approval for a rental," says the director of the organization, Matsuda Akira. "The people who come to us have usually been turned away by real estate agents."

Government campaign falls flat

The irony is that Japan has as many as 4.5 million vacant rental properties. In 2017, the government proposed a range of initiatives in a bid to connect at least some of these empty homes and apartments with elderly people who are looking for housing.

It asked landlords who are willing to take older tenants to register their properties as "safety net housing," making them easier to find. It also asked prefectural governments to provide financial support to organizations that help the elderly apply for rentals. And to address the concerns of landlords, it drafted a model contract clause which allows rental applicants to stipulate a third party who will dispose of their possessions in the event of their death.

But a survey this year suggested that these changes have made little difference. The poll found that fewer than one in four applications for housing by elderly tenants were successful. Among the reasons: "safety net housing" accounted for less than 3 percent of the rental properties subject to application; few of the applicants knew they could call on the help of support organizations; and landlords rarely used the government's model clause in their contracts.

"There have been cases where tenants have been turned down simply because of their advanced age, even if they have sufficient savings," says Yoshinaka Yuki, executive director of the National Council of Housing Support Corporations, which conducted the survey. "We're seeing these problems even in rural areas, where there is supposed to be a surplus of housing. The challenge is how to dispel the concerns of landlords."

Legal experts are in agreement ― the system is a mess. "We have all these vacant houses that are unavailable for rent," says Professor Matsuo Hiroshi, from Keio University's graduate school of law. "The rental system is broken. It may be necessary to establish a law that clarifies the authority to dispose of leftover property."