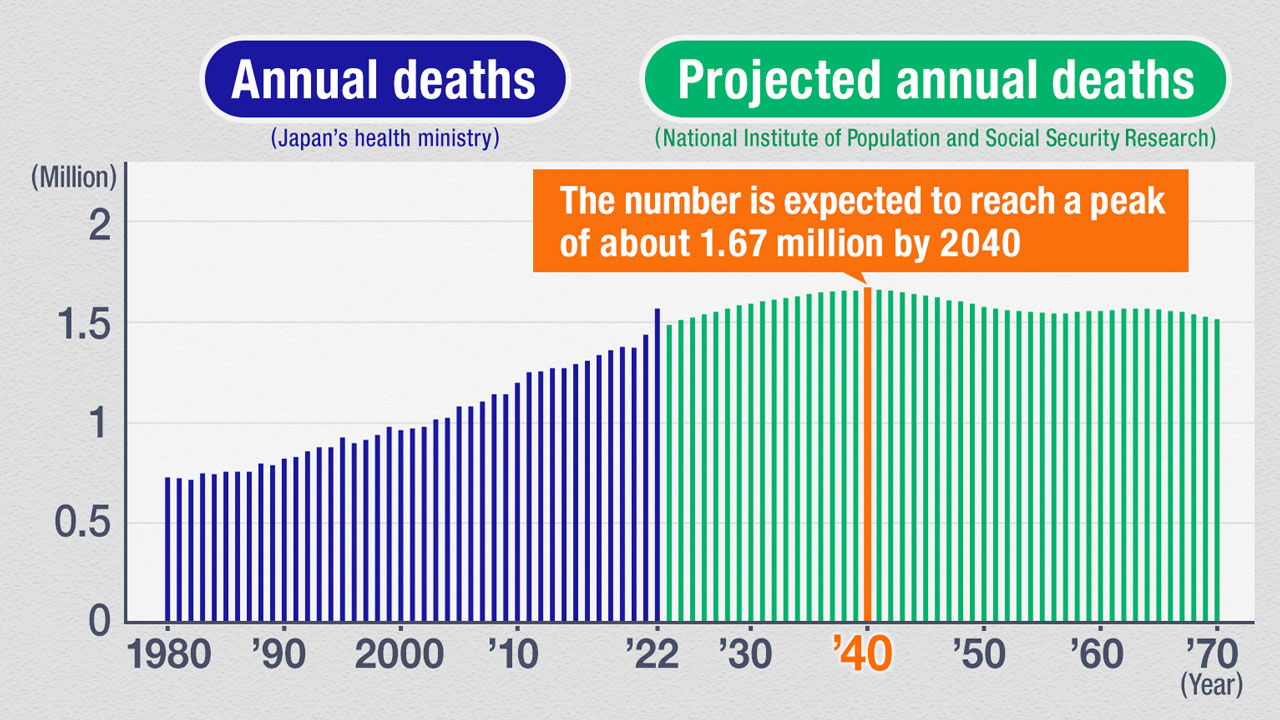

According to Japan's health ministry, the number of deaths during the 2022 calendar year was up by 8.9 percent from the previous year. Over the past two decades, it has increased by 150 percent.

The most recent statistics, from 2022, show the leading cause of death is cancer, which claimed the lives of 385,787 people, or almost one quarter of the total. Other major causes are heart disease (232,879), old age (179,524), vascular brain disease (107,473), pneumonia (74,002), and coronavirus (47,635).

Cremation delays

Among the many families who have had to deal with long delays is a woman in her 40s from Chigasaki, Kanagawa Prefecture. She lost her 94-year-old grandmother in February this year.

The woman made the necessary arrangements with a funeral company to save her elderly parents from the difficult task. She chose a simple plan that allowed people to pay their respects at the crematorium without a funeral service. But the earliest available cremation date was 11 days after her grandmother died.

The family was charged 13,000 yen (90 US dollars) per day for storing the body. They tried to find another crematorium that was able to offer prompter service in a different municipality, but the transportation fees made it uneconomical.

"The cost was a big burden for my parents, who are pensioners. It was a long wait, and expensive, and I was really surprised by that," says the woman.

Cold storage for corpses

Tatumi Kogyo, an equipment manufacturer in Kawasaki, Kanagawa Prefecture, says the number of orders it received last year for refrigerators used to store corpses was up five-fold compared with 2019.

This year, the company is seeing even more demand from funeral homes and crematoriums.

Cremations even on 'unlucky' days

Some municipalities are trying to increase capacity by renovating or constructing new crematoriums, mainly in urban areas where delays are a problem.

In Yokohama, near Tokyo, four municipal facilities cremated 34,000 bodies between them last fiscal year. The average wait time now is five to six days. To get that down, the city is working to improve services and convince people to book cremations on supposedly unlucky days, such as tomobiki.

Tomobiki translates as "pulling your friend with you" and is usually avoided for funerals and cremations. But with four to six tomobiki days each month, the superstition contributes to the backlog in cremations.

Yokohama is also planning to construct a new facility that will start operating in three years. A maintenance manager at the city's funeral hall, Yamaguchi Makoto, notes: "Demand keeps going up, and we have to respond to that. We need to improve existing facilities, and develop new ones."

The cemetery next door

Takeda Itaru, representative director of the Association of Research Initiatives for Cremation, Funeral, and Cemetery Studies, is hoping to change another entrenched public mindset. He says planning for new crematoriums routinely faces delays because "some local governments struggle to obtain land and consent from residents," who feel uncomfortable about having a place of death in their midst.

"Many people will resist a crematorium being built nearby," he says. "For that reason, we might need to think more about where they are built to change people's perceptions, even considering scenic locations."

Planning ahead

According to projections compiled by Japan's National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, the number of annual deaths will remain high even after the 2040 peak. The figure is expected to exceed 1.5 million per year until 2070.

Kotani Midori, representative director of the Senior Research Institute for Life and Culture, helps people prepare for the end of their life. "As the population ages further, issues will arise with families unable to support the deceased, and with the increasing number of people mourning losses.

"It's important that people discuss with their families how they want their lives to end, who to tell after they die, and also to have relationships with people outside family, such as friends and neighbors, to whom they can entrust their wishes while they are still healthy."