Rising Unicorns

One of the world's most well-known unicorn firms is the US ride-hailing service provider Uber. Born in San Francisco, it made a breakthrough in the peer-to-peer ridesharing business and currently operates in more than 70 countries. Some call it the "world's largest cab company that doesn’t own a single taxi."

Another example is Airbnb. Again, some people dub the company the "world's largest hotel chain that doesn’t own a single hotel."

Chinese unicorn Xiaomi, which some people refer to as “China’s Apple,” has become the world's 4th-leading smartphone maker in just 8 years.

These firms have entered the market without the facilities, equipment and manpower that the major, established firms have. Instead, they’ve employed innovative business models to create completely new markets, rather than grabbing market share from competitors.

These firms are also known for their quick decision-making as they are not publicly listed and bound by shareholders' views. Their number has been rising every year.

Japan lags behind

This year, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s government set a target of creating 20 unicorns or listed equivalents by 2023. It’s the first time the government set a numerical target in its annual growth strategy.

The government has been trying to find new ways to achieve economic growth in the face of a rapidly aging population. Its target suggests a concern about being left behind. But it also raises the question of how ambitious the goal is.

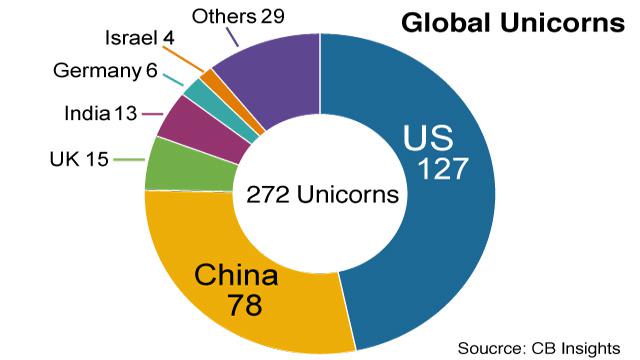

According to a recent list from CB Insights, the US ranks number one with more than 120 of the 272 unicorns in the world. China is 2nd. It is home to 78 unicorns and is quickly catching up. The country has been sharply and strategically increasing its investments in venture capital over the past 3 years.

Business leaders are also paying close attention to India. The country has only 13 unicorns, lagging far behind the US and China. But its number is steadily rising. Observers say India's vast pool of talent in the information technology sector is attracting money from both US and Chinese investment funds.

In Japan, there is now only one unicorn -- Preferred Networks. The famed unicorn, Mercari, went public in June, hoping to expand demand overseas for its flea market app. Preferred Networks specializes in technology using AI. It has received roughly US$90 million in investment from Toyota Motor. Why does Japan have such a limited number of unicorns?

In my view, there are 3 contributing factors.

First, there's a considerable shortage of risk money needed to nurture unicorns in Japan. A government report notes that venture capitalists in the country invest only 1/80th that of their US peers.

Secondly, Japanese are still bound by the myth that companies can't be considered “first class” until they go public. Many startups have been asked to make a commitment that they will go public within a few years to get funds from venture capitalists and other investors. But companies working towards such a goal can end up focusing on immediate profits, and that makes it difficult for them to take risks and make large investments. In fact, an increasing number of companies are struggling to expand after becoming listed.

And lastly but most importantly, Japan has too few entrepreneurs and connoisseurs. In the US, there are many cases where heads of successful venture firms launch their own venture capital funds to support next-generation entrepreneurs. But Japan has seen very few such cases. Whether Japan can create an environment that can kick start such a virtuous cycle is in question.

Nurturing Japanese unicorns

So, what can Japan do to increase the number of unicorns? One solution is to provide more funds, both from the government and the private sector, to ventures with growth potential. State-backed funds such as the Japan Innovation Corporation can play a more important role. Support for university startups should be strengthened. And with historically low interest rates, major Japanese firms can boost their investments in venture firms.

The government can also do more by reviewing how it can support ventures. It has made an effort to create an environment conducive to the creation of new companies. But it may not be giving enough assistance to help existing venture firms grow bigger. In June, the government started a project called J-STARTUP to assist entrepreneurs. It picks about 100 promising companies from among 10,000 ventures launched annually. It then identifies problems faced by the entrepreneurs and offers them knowhow, manpower and money. But more support is needed to help those companies make inroads into foreign markets and procure funds to expand business.

Japan saw a venture boom more than a decade ago. But it was short-lived because of the global financial crisis triggered by the collapse of US major investment bank Lehman Brothers. That boom has not revived.

Thanks to new technologies such as artificial intelligence and cloud computing, hurdles to launching new businesses are lowering. Entrepreneurs don't need to own large-scale equipment and human resources to start a new business.

In order for unicorns to become the driver of Japan's economy, a continuous, long-term effort will be necessary.